Haz clic aquí para leer en español

The effervescent Futaleufú River roared and roiled beside us as we walked toward its namesake town. The name is derived from native Mapuche’s word meaning “Big River.” Camping on its sandy shore one evening we watched a daredevil pair of kayakers whip past. The next evening we bathed in one of the many lakes.

The town itself was a restful stop, set in a valley below rounded peaks. The locals were friendly and welcoming, their industry was largely based around the natural recreational wealth of the region, and it has a lot to offer: river rafting, fly fishing, rock climbing, hiking; there is a reason this is an adventurer’s town.

Leaving, we crossed the border into Argentina, where we quickly found our way onto the Huella Andina. Large billboard signs mark the beginning and ending of the various segments of this well-marked trail, its bridges and even – for some unknown reason – turnstiles.

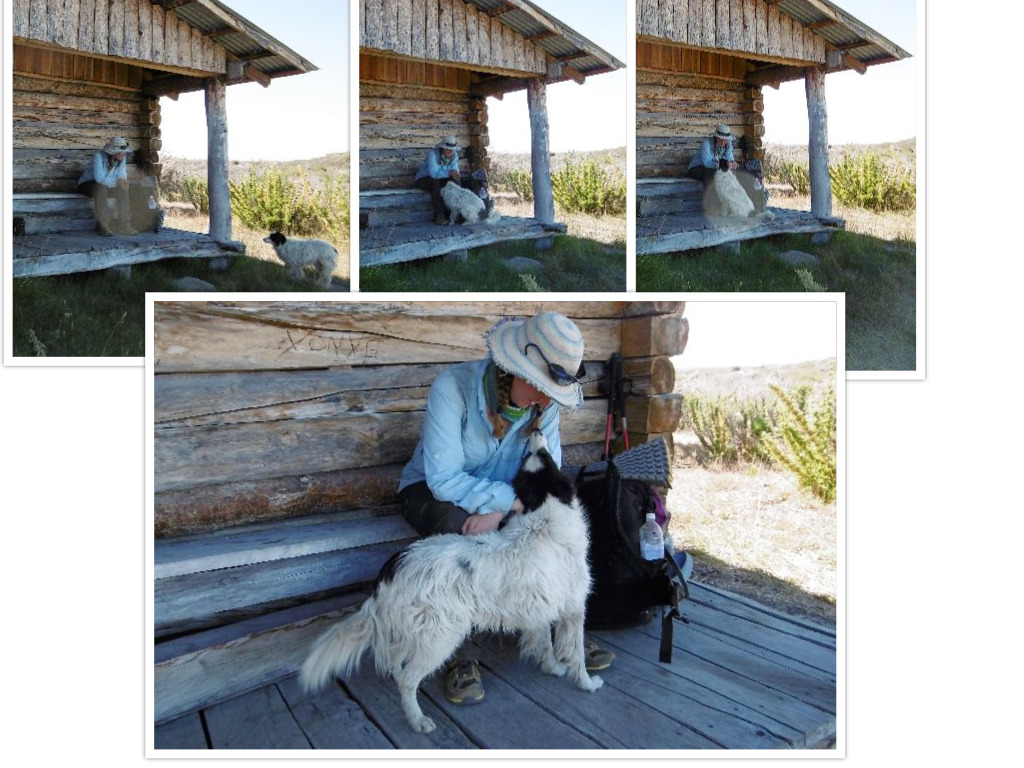

As we pass through the settlement of Aldea Escolar, a pretty little Border Collie trotted out of one of the yards to greet us. We have become accustomed to dogs joining us around towns. Often enough that we call them “tour guides.”

Dogs throughout Patagonia have a high degree of autonomy. They roam solo or in packs on the streets of most of the towns we have passed through. They generally mind their own, though we have heard stories of people being bitten. Some have homes and are allowed to wander, but most are abandoned.

They seem to survive by scavenging. Many people simply throw expired food onto the street, where it is summarily gobbled up. Some of the larger cities are seeing a movement of people putting dog beds and food out on the street. We have seen several wearing sweaters and others have collars, even if no actual owner. It seems some of the dogs make a decent life of it.

They are not stupid animals. We’ve observed them organize into a pack to chase cars, with a watcher sounding the alert then the others dodge out from different corners nipping at the tires and bumper, so far *always* just avoiding being run over.

Also being street loiterers in town, we’ve come to accept their presence, and after giving us a good sniff, they generally accept and ignore us as well. I am always afraid, heading out of town, one will follow us too far. As much as I would love, and at its inception dreamed, of having a dog on this journey, the logistics of border crossings, National Park bans on dogs, and the nature of the situations we get into make that unwise.

Leaving the community with the dog hot on our heals, we entered a reforestation area behind a huge gate where we had been warned we would not be well received. We tried to tread quickly and quietly but about a kilometer in to the preserve a truck pulled up. The conversation with the groundskeeper is pretty typical:

“You can’t be here. You have to go to the office and get a permit. If not, a wandering back country ranger could fine you heavily.”

“The office was closed when we passed.”

“It is open Monday through Friday, 9 am to 4 pm,” replied the guard. It was 2 pm on a Thursday.

Me, “. . . ”

Him, “. . .Is that your dog?”

“No sir.”

“Well, you can’t be here. Also, no campfires.” He eyed us one last time before hopping in his truck and heading back as we proceeded and made our way up into the hills, feeling relieved once we had put a few hours of undrivable mountain tracks between us and him.

The dog was still there. When I tried to shoo her away she just rolled over, tucking her tail between her legs and stared up at me contritely.

The next days took us through territory where there was not trail and we spent it in the hills, fighting through a bamboo jungle, crawling on hands and knees through mud. It was a matter of great hope when we had dilapidated fence lines to follow.

All the while “NoMio,” as we came to call her, trotted along happily. In the evenings she enjoyed dinner of rice and tortillas and at night she bedded outside the tent, methodically picking burrs out of her coat. Every morning she was tidy and so excited to go that it was offensive to those of us who are not morning people.

The last couple dozen kilometers toward Villa Futalafuquen, gateway to Los Alerces National Park, the Huella Andina mercifully resumed, as Neon had become ill.

Como dejar Futaleufutú fue a los perros

Traducción por Henry Tovar

El efervescente Río Futaleufutú rugía y se agitaba junto a nosotras mientras caminábamos hacia la ciudad del mismo nombre. El nombre se deriva de la palabra nativa de mapuche que significa ´´Río Grande´´.

Acampando en la orilla arenosa por la noche, vimos un par de temerarios kayakistas pasar rápido. La siguiente noche nos bañamos en uno de los muchos lagos.

La ciudad en si era una parada de descanso, situada en un valle debajo de los picos redondeados. La gente era amable y acogedora, su industria se basa en gran medida en torno a la riqueza recreacional natural de la región, y tiene mucho que ofrecer; rafting, pesca, escalada, senderismo, hay una rason por la cual este es un pueblo de aventureros.

Saliendo, nos encontramos con la frontera hacia Argentina, donde rápidamente encontramos nuestro camino hacia la Huella Andina. Grandes avisos marcan el comienzo y el final de los distintos segmentos de este sendero bien marcado, sus puentes e incluso, por alguna razón desconocida, torniquetes.

Al pasar a través del asentamiento Aldea Escolar, una bonita y pequeña Border Collie salió a uno de los patios para saludarnos. Nos hemos acostumbrado a perros que se nos unen alrededor de las ciudades. A menudo basta con que los llamamos ´´guías turísticos´´.

Los perros en toda la Patagonia tienen un alto grado de autonomía. Ellos deambulan en solitario o en grupos en las calles de los pueblos por donde pasan. Por lo general, se preocupan solo de ellos mismos, pero hemos escuchando historias de gente que ellos han mordido. Algunos tienen casas y se les permite pasear, pero la mayoría están abandonados.

Ellos parecen sobrevivir hurgando en la basura. Muchas personas simplemente tiran alimentos caducados a la calle, donde se juntan sumariamente. Alguna de las ciudades más grandes está viendo un movimiento de personas que ponen camas para perros y comida en la calle. Hemos visto varios con suéteres desgastados y los demás tienen collares, incluso si no hay dueño real. Parece que algunos perros hacen una vida digna.

No son animales estúpidos. Los hemos observados organizarse en un grupo para perseguir autos, con un vigilante sonando la alarma y luego los otros esquivaban desde diferentes esquinas mordiendo los neumáticos y parachoques hasta ahora siempre evitando ser atropellados.

Siendo también los vagos de la calles de la ciudad, hemos llegado a aceptar su presencia, y después de darnos una buena aspiración, por lo general, aceptamos y los ignoramos también. Siempre tengo miedo de salir de la ciudad, unos nos siguen demasiado lejos. Por mucho que me encantaría, y en su inicio soñado, de tener un perro en este viaje, la logística de los cruces fronterizos, y las prohibiciones de perros en el Parque Nacional, y las situaciones naturales en que nos metemos hacen de eso algo imprudente.

Dejando la comunidad con los perros calientes en nuestros talones, entramos en un área de deforestación detrás de una enorme puerta, donde nos habían advertido que no seriamos bien recibidas. Tratamos de pisar rápidamente y en silencio, pero alrededor de un kilometro en la preservación un camión se estacionó, la conversación con el jardinero fue bastante típica:

´´no pueden estar aquí. Tienen que ir a la oficina y obtener un permiso. De no ser así un guardia de los que caminan por aquí podría ponerles una gran multa´´.

´´la oficina estaba cerrada cuando pasamos´´.

´´está abierta de lunes a viernes, de 9am a 4pm, ´´respondió el guardia. Eran las 2 de la tarde del jueves.

Yo ´´….´´

El ´´… ´´es ese su perro?

“no señor”

“bueno, no pueden estar aquí. Además no hay fogatas, “nos miraron por última vez antes de saltar en su camioneta y de volver a medida que avanzábamos, nos dirigimos a las colinas, sintiéndonos aliviadas una vez que había puestos unas cuantas horas en el camino de la montaña entre ellos y nosotras.

La perra seguía allí. Cuando trate de espantarla y alejarla ella simplemente se dio la vuelta, metiendo su cola entre las patas y se quedo mirando hacia mi.

Los próximos días nos llevaron a través de territorios donde no había camino y pasamos en las colinas, luchando a través de una selva de bambú. Arrastrándonos a gatas por el barro. Era una cuestión de gran esperanza cuando tuvimos una cerca que seguir.

Durante todo el tiempo “NoMio”, como llegamos a llamarla, trotaba alegremente, ella disfruto de la cena de arroz y tortillas, y por la noche se acostó fuera de la tienda, recogiendo metódicamente partes de su abrigo. Todas las mañanas estaba ordenado y muy emocionado de ir que era ofensivo para aquellos que no somos de la mañana.

El último par de docenas de kilómetros hacia villa Futalafuquen, puerta de entrada al Parque Nacional Los Alerces, la Huella Andina misericordiosamente reanudó, al tiempo que Neon se enfermó.

Comments (7)

Do you need anything?

Sent from my iPhone

>

Thank you very much for thinking of us Russell. For now we have everything we need. Keep following along here and on FaceBook though and we will keep you posted.

What a sweet dog to watch over you!

She really was.

I like that perspective, Cliff, thank you.

Interesante Blog – “Her Odyssey”.

Gracias!

Pingback: Dog Tales – Her Odyssey