Were not wise sons descendant of the wise,

and did not heroes from brave heroes arise.

-The Odyssey

Written by Fidgit

Patagonia took us almost 4 months to cross on foot at the price of blood, sweat, tears, close encounters, and disease; it will always hold a piece of my heart. Lately, as many of you have probably noticed, it’s been in the news. Much of the press to arise regarding the Tompkins land donation to the Chilean government focus on the act of the gift, but fail to address whether Chile’s park system is prepared to manage it. The key element to the success of this historical event will be the interplay of private and public lands, specifically regarding those intended for conservation.

This is a massive and complex topic. My endeavor here is to look at the gift in light of the condition and diligence which exist in Chile currently, what these parks systems demand, and how we need to revolutionize them. To that end I draw on a variety of sources ranging from experiences in the field to research articles.

I am going to break the article into pieces. The aim will be, first, to explain what has recently transpired regarding the Tompkins donation to Chile; then, to give a bit of background on the major players. From there, I will highlight some of the thoughts of affected parties; and finally, try to pull it all together with perspectives for moving forward.

What just happened

In short, something unprecedented.

In March 2017, Kristine McDivitt Tompkins, the widow of Doug Tompkins, signed a pledge with Chilean President, Michelle Bachelet, to give over 1 million acres of the Tompkins’ land and park infrastructure to the Chilean government. This is generally agreed to be the largest land donation from a private entity to a government in history. The Tompkins Foundation leveraged the gift into converting 11 million acres of land into national parks.

What Kris and Michelle signed was a pledge; essentially, a millionaire and politician’s version of a pinkie promise. Chile then announced a plan to rename the Carretera Austral the “Route of Parks,” accessing some 17 current and proposed national parks. It seems the Tompkins’ focus is, and always has been, on conservation; however, what I have seen to date from the Chilean government is more focused on driving the growing tourism industry in the region.

While these things are not mutually exclusive, they could lead to a long term disparity. As the research paper by David Tecklin and Claudia Sepulveda “The Diverse Properties of Private Land Conservation in Chile: Growth and Barriers to Private Protected Areas in a Market-friendly Context” puts it, “legal property theorists have long highlighted the dynamic, highly social, and complex character of property rights, and have pointed out the inherent tensions between the different purposes that property is meant to serve. “

No matter how you look at it, this pledge is an indicator of the beginning of a turning point. Now the hard work begins, and how it is handled will decide the fate of Patagonia and her people. As one American conservationist put it, “The one looming issue has been that they are making the donation without an accompanying management endowment, and it seems clear that neither country [Chile and Argentina] will be able to adequately steward such huge tracts.”

He elaborates, “But Tompkins Conservation and some other very smart people have been working behind the scenes to raise the money and develop the technical capacity to ensure that there will be a substantial focus on managing the new parks. And of course they have been brilliant about leveraging very large land matches from the Chilean government.” The vision and hope seems to be that this gift motivate Chile and its people to step up.

In an interview with NPR, Kris explains, “we [she and Doug] grew up within the national parks here in the United States. And there is a sense of, I would even say, ownership by every American who goes through the front gates of Yellowstone or Yosemite, that those are public parks. They belong to everybody. And Chile is no different. We hope that somehow between the creation of national parks, the development of what we call economic development as a consequence of conservation that precious masterpieces of the country will be preserved forever.”

In short, this is one of the most massive leaps of faith our generation has seen.

Background about the players

In this section I seek to give a summary of Patagonia, The Chilean Government, CONAF, and the Tompkins.

Patagonia was named for a mythical tribe of giants, called the Patagones, or “big feet.” The earliest written documents come from European explorers in the 1500s, such as Magellan and Sir Francis Drake, whose contact was limited to being by boat, as the focus at the time was on the Spice Race.

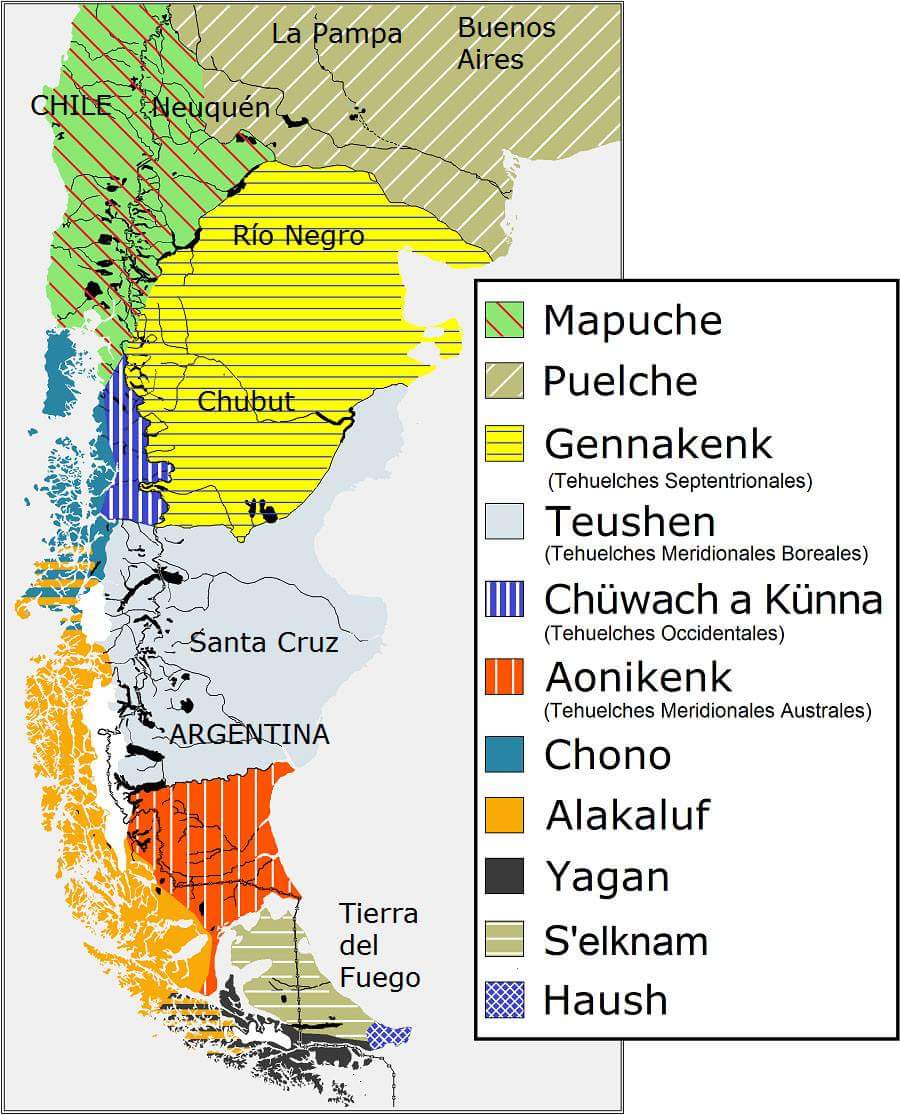

The fjords, austere peaks, glacier fields, and tangled forests, left the inland regions largely to the natives, such as the Tehuelche and Mapuche, for several hundred years more. Settlers began to move into the area in the late 1800s both from Europe and inland. Around this time Argentina and Chile began sparring for control of the territory. In 1818, thanks to the efforts of San Martin, Chile emerged from under Spanish rule.

In the last 50 years the Chilean Government has moved between socialism, dictatorship, and democracy. Much of the infrastructure in southern Chile, as well as land and resource privatization across the country, happened under the dictatorship of Augusto Pinochet, who ruled from 1973 to 1990. The Carretera Austral, for example, was one of his pet projects. The cost in human lives and freedom which went into it, is cause for a lingering distaste among many Chileans and ostensibly, is why progress on the Carretera Austral has been slow in past decades.

For a long time Patagonians did not strongly identify with either Chilean nor Argentine central governments. As we walked across the region, we spoke with several people who remain resentful and mistrustful of the central powers, expressing that they were ignored until the exploitation of renewable energy resources (largely water reserves, both free flowing and in glaciers) drew attention. In speaking with one 3rd generation Patagonian he said, “first I am Patagonian, second I am Chilean.”

Today it is one of the final frontiers. The modern day wild west. And tourists are flocking from all over the world. Prices have soared accordingly.

The government has moved aggressively in recent decades to capitalize on natural resources, ranging from dams in Patagonia to solar in the Atacama. Again drawing on the work of Tecklin and Sepulveda, Chile’s distribution of property rights divides them “to an extreme level.” Various legal and constitutional sources have set it up such that “rights to freshwater, subsoil minerals, geothermal water and energy, and the coastal inter-tidal zone are all fully separate from land or ‘real property’ itself. Under these specific laws third parties can constitute rights that overlap physically and functionally with land property, without any priority of access on the part of the landowner.”

Dividing up rights to resources in this way has serious effects both on people who live on and own land in Chile. For example, it restricts residents on use of water flowing through their yards. They watch unhappily as rivers in their communities are dammed (as we wrote about last year). Even for someone with access to funds and desire to own all the rights as a part of their property, no privately protected area in Tecklin and Sepulveda’s study, “has been able to systematically acquire and hold rights to all resources within its boundaries. This is due to the legal and administrative complexities, the high costs of soliciting or maintaining rights, and political opposition to such consolidations.”

Vast tracks of Chile’s land have been decimated by logging and other profit-oriented efforts. One which stands out in my mind was as we began walking, south even of Patagonia, along the senos around Punta Arenas. Climbing the hills outside of the port city we moved into gale force winds sweeping across where a once mighty forest of Arctic Beech had stood. The weathered stumps stretched as far as we could see. We ended up taking shelter from a snow storm that night in a single remaining square of trees.

Meanwhile the town below was rebuilding bridges and widening waterways for the ever increasing floods which wash through the city streets annually from the Río Las Minas. The once narrow valley above the city had been stripped to make way for a mine (which has since ceased to produce and been abandoned), the trees which held together the banks of the valley were still being removed based on the theory that when the floods come, it is the washed out trees which do the most structural damage, so if trees are removed then the flooding will be less of an issue. Thus, the floods each year, widen the valley ever further. Standing on the crest of that valley, looking down at the city, I saw several small dams, intended to stymie the floods, which had been washed out as well.

In 2012 the Tompkins put a lot of resources into a fight against the creation of an altogether different kind of dam. Patagonia Sin Represas was and is a social movement which at its height, turned into an all out showdown between the scant population of the Aysén Region and ENDESA, a subsidiary of ENEL (a multinational manufacturer and distributor of electricity and gas). It began over their building HidroAysén, one of 5 mega-dams, which would flood massive tracts of national park and private land. The dam project had passed all the environmental impact studies and had the backing of the Chilean government, and particularly from then Chilean President Piñera. Only after a drawn out legal battle, was the project rolled back (though the mega dams continue in other regions).

CONAF, the National Forest Corporation, the Chilean public/private hybrid version of a Forest Service, was created in 1970 and is tasked with managing national natural resources and parks. Most of the park employees we encountered when hiking through parks were CONAF employees, who draw on a large community of young volunteers, generally heralding from Santiago. Again, citing Tecklin and Sepulveda, this institution, “has remained in a legally precarious and chronically underfunded situation (Espinoza 2010). Political discourses around the public PA system have been poorly articulated, reflecting the low priority that it has received since its inception.”

From early in our interactions with the park guards it seemed clear their main interest is to make as little work for themselves as possible. A few times when I felt I could inquire, they cited that they were not paid enough to do anything more than the bare minimum.

Maintenance even on some of the most famous trails (The “W route” of Torres del Paine, for example) was not exactly inspiring. Free camping sites across most parks were usually trashed and often where there were restrooms, they were locked and water was shut off. When we asked, they explained these were free campsites and if we wanted amenities, such as sanitation, we needed to go to the private pay-sites.

Our experience of the Chilean parks’ inefficiency came to a culmination in February 2017 when, as fires were raging on the coast, we came in to Parque Rio Clarillo just south of Santiago, as usual, from the back way, descending from the mountains. The park seemed abandoned. We wondered at this, until we exited the front gate and passed through 4 rounds of CONAF employees telling us we couldn’t be there because all of the national parks were closed. Why? Due to fires burning in a different region, posing no threat to that area. That’s right, CONAF shut down nature. Sound familiar? (I’m looking at you, USA circa 2013 Government Shutdown).

One more example of the Chilean government’s lack of follow through, which particularly galled me, is all the website information and books available for purchase by and for the “Sendero de Chile.” Rolled out by the Chilean government to celebrate the 2010 bicentennial of the country, originally it was aimed to create an 8,500 km long trail running the length of the country. A lot of money and resources went into the initiative up front. They even flew in trail builders from around the world to teach CONAF and volunteers how to build trails. As the initial funds and enthusiasm shriveled, so did that dream. A story which has played out time and again on many fronts in Chile, as the government has changed hands time and again.

Chile, in its current political iteration, is quite young, being only decades old in many ways. In a recent conversation, a friend reminded me that in early exploration, everyone makes mistakes. The editors of this piece have time and again reminded me of the importance first to give context and grace. Action and accountability can and must also be woven in, to generate progress. Information, preparation, determination, and renovation are keys to moving forward. While Chile is young, what the Tompkins are doing is heretofore unheard of.

The final major players in this story are Doug and Kristine Tompkins. In the 1960s, Doug Tompkins co-founded and ran the North Face and Espirit brands with his first wife. He fell in love with Patagonia and his second wife, here referred to as Kris, in the 1990s. He came to know these lands deeply, making first ascents and exploring unnamed peaks and lakes. Private Protected Areas [PPA] began to appear in Chile in the late 1980s, early 1990s, and Doug and Kris were at the forefront. Their focus was on land conservation and environmental activism. To realize their vision they bought massive tracts of land across Chile and Argentina and began ‘rewilding’ them by removing ranches, fences, and other structures.

According to Tecklin and Sepulveda, “In the absence of a legal framework for private conservation, the Tompkins have used multiple strategies, none of which fit well with market-based characterisations of private land conservation. These have included attempts to weave together existing legal tools and ownership structures to make the future sale or exploitation of conservation lands difficult. Primarily, however, they have sought to pass property to the Chilean state for the creation of national parks, including Tompkins’ offer in 2012 to donate all of his large properties in Chile for this purpose.”

They were able to initiate conservation efforts across a scope well beyond most measures. According to a Montecarlo Time article, “Asked why she focused her efforts in South America, [Kris] Tompkins noted that the conservation potential was large—some areas were threatened by logging and intensive agriculture—and the land relatively cheap.” The unprecedented breadth of their work goes beyond the amount of land they held and delves into the scope of projects (see Tompkins Conservation Website).

As one of our editors adds, “They were able to protect land at an enormous scale, allowing them to accomplish truly world-changing conservation. Who remembers the political skirmishes that dominated the debates over the creation of places like Yosemite, Yellowstone or the Adirondack parks in the US? The people who created these places are now unanimously heralded as visionaries. And I think that it is very likely that that the Tompkins’ will be remembered the same way in 100 years.”

The Tompkins are invested in “rewilding” and ascribe strongly to a structure of ideas which I am not equipped to fully or fairly explain. One of these ideas with which I am familiar is the “Half Earth Project“ which was proposed by my favorite ant man, E. O. Wilson in his book Half-Earth which, “proposes an achievable plan to save our imperiled biosphere: devote half the surface of the Earth to nature.”

Much like my understanding of Doug himself, it was all or nothing. Either the lands are wild, or their use is hurdling us deeper into the extinction crisis of the Anthropocene age. Again by contribution of one of our editors, “there are far too few conservationists working to create forever wild, ecological reserves. The great majority of us make deep compromises to accommodating a variety of sustainable land uses, notably agriculture and forestry, which sometimes is genuinely sustainable, and often is not.”

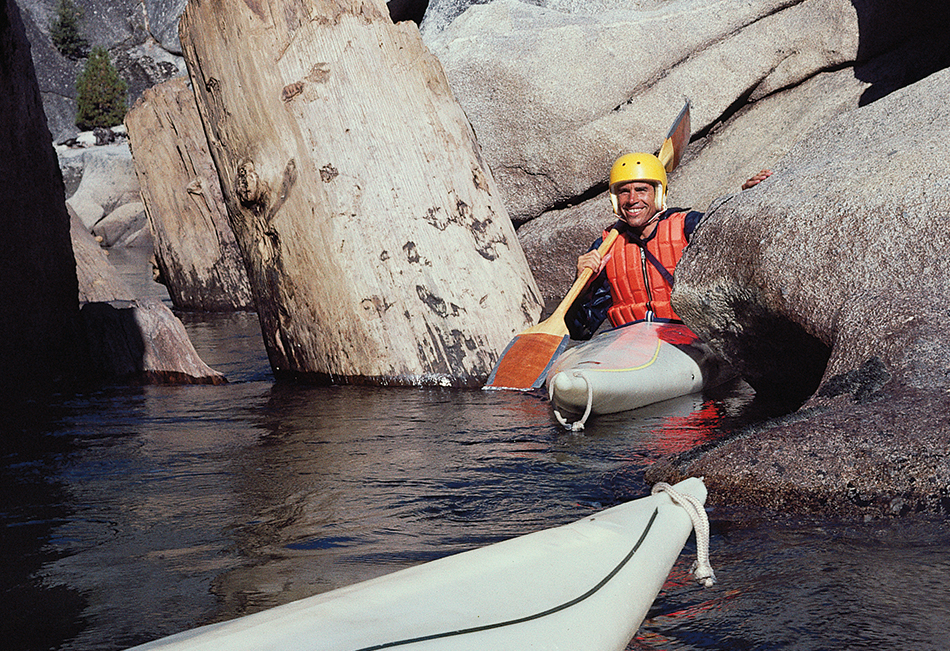

Douglas Tompkins died living out Edward Abbey’s call, “it is not enough to fight for the land it is even more important to enjoy it while you can, while it’s still here.” He perished after a kayaking accident on Lago General Carrera in 2015. We passed there on our hike the next year and as I gazed out across the choppy blue lake, I wondered whether there is any better way to meet the end of one’s life than among friends, doing what you love, and fighting diligently and as best you know how for what you believe in.

The reasonable man adapts himself to the world; the unreasonable one persists in trying to adapt the world to himself. Therefore all progress depends on the unreasonable man.

~George Bernard Shaw

Contemplations and Concerns

In this section, I outline some of the concerns and questions to arise around this land gift. In short these are: some straw man arguments, impugning sense of national identity, concern for losing the frontiersman, whether this move makes it accessible to the local population, and whether the government is really going to be long-term stewards of the land.

Let’s start with the straw man arguments. There were and still are outlandish accusations that the Tompkins’ actions were a land grab to establish a Jewish state, that they were members of a cult, or were setting up a base for CIA spies to intervene in national affairs. These are generally regarded as laughable by everyone from the ground level up and are withering with time and, particularly, in light of Kris’ pledge.

The Tompkins’ land acquisitions were met with skepticism from many Chileans. In 2016, we were still seeing “Patagonia sin Tompkins” bumper stickers, a response to the “Patagonia sin Represas” stickers from the 2012 battle cited above, which we saw far more often. This is the uphill battle against old ways of thinking.

A sense of national pride has been injured by having a foreigner intervene in such a huge way. As Marcela from Villa O’Higgins, reflects, “it is difficult in these times to understand a person, a philanthropist, a conservationist on top of that, is difficult to accept. Especially when consumerism makes you only see one thing, that those who have money want more and not to give it away, as he has done.” That said, Doug and Kris’ actions go against MOST people’s way of understanding.

Still, there are reasons for sentiments against outsiders purchasing large tracts of Chilean land. One example is the German businessman Víctor Petermann. As Jan explained in his comprehensive rundown of the Greater Patagonian Trail:

During the later days of the Pinochet Regime large parts of the state owned forest around the Lago Pirihueico were sold under obscure circumstances to the German immigrant Victor Petermann. He later converted the forest into a “private for profit natural reserve”. The emphasis seems to be the profit and not so much the natural reserve. Permanently manned gates now limit access to guests of the luxury resorts on this immense property. Wood logging continues in more hidden parts of the “profit reserve”. When we attempted to take the former public road from Puerto Fuy to Pirihueico we were turned back on several of the gates.

It seems reasonable that after almost two decades of having large tracts of their land sold by Pinochet to wealthy foreigners, locals were dubious of the Tompkins purchasing thousands of hectares, and promising to one day return the lands to the interest of the people. This was a promise existing against the backdrop of dozens of examples of underhanded manipulations, and the Tompkins’ efforts are entirely unprecedented anywhere.

A second concern we heard was if Doug did give the land back, whether it would be accessible for locals’ purposes (largely ranching). This relates to a concern about loss of Chilean identity, edging out the way of the gauchos. The quintessential Chilean cowboy, the legend, Don Rial, who has worked the remote valleys between Villa O’Higgins and Cochrane, delivered his favorite one-liner on the matter, saying “the Tompkins are making a ranch for mountain lions and guanacos.”

As a friend from Cochrane explains,what he sees as the primary local concern is, “that we have lost our culture and an activity which defines these lands, which generates identity by working livestock, which, to some extent, is true.” From what we observed, the Patagonian settlers are hard workers and, by and large, good stewards of the land, though the temptation of an easy buck, when laid on the table, is hard to pass up.

The Tompkins’ ethos does not leave room for the residence of settlers maintaining the ranching lifestyle, instead it focuses on redirecting them. As our conservationist cited above points out, “As for local people, there has been the misconception that the Tompkins were not supportive of local communities. My observation is that the opposite is true in Chile. They have engaged with and employed local communities and been good for local economies.” At the same time, it is clear that much of the efforts on their reserves have engaged volunteers from abroad to help dismantle the fences and settlement structures of the pioneers, while construction crews raise eco-friendly, posh lodges.

Whereas an outsider might see those who choose to live on the frontier as impoverished, they make and cultivate almost everything they need and often seemed quite content and, we found, were happy to share what they have. What is more, removing them from the land and prohibiting their way of life takes away what they draw pride from, working animals and knowing the land. Removing these people, who worked the land all their lives, forces them to move into towns and cities; thus, placing them on the lowest wrung of a chain they never wanted to be on in the first place. Dismantling the frontier structure and pushing the settlers out is a black or white move which removes perhaps the most knowledgeable, invested, and grounded stewards.

In the Montecarlo article cited earlier, “Reflecting on why she [Kris] was donating her private parks to Chile, she told an audience at Yale University last year, “We could have locked up our land; it would have been cheaper. But if you don’t make your land public, you’re losing half its value.” The implication is that the land being accessible to the general public is important to informing that public so they will work to brighten their own future.

This leads to the next question, will this land gift open the door and attract the general public?

Following the path of least resistance and current precedent in Chile would mean, no, it is not accessible. Current trends are already moving in that direction. At least not to the general public and even less so the average Chilean. As Matias, one of the more illuminated wilderness guides we have met along the way explains it:

“Monetarily it is ever less accessible for Chileans to get to know and explore our own mountain ranges. The prices of services are through the roof, that combines with the lack of vision and commitment to safeguarding and protecting the environment. In my opinion it is the exploitation of tourism lodges without mitigating measures, nor protection to the flora and fauna. In Torres del Paine you no longer see birds along the trails. The entrance and camping fees make it impossible for a Chilean of middle means to know these places. Much less schools/students.”

Recall, we are contending with a similar issue in the United States. Locals are not engaging with their parks next door. The USA Parks systems are severely lacking “in their consideration for local community development and supporting that in a sustainable way- the core focus has been on tourism and tourism dollars, which is now leading to the US visitors ‘loving their parks to death,'” as Greta, an adventurer and sustainability thought partner who lives and works in Chile, notes.

It is widely acknowledged, even among Chileans themselves, that most Chileans have a garbage problem, in that they throw it everywhere. We saw this being manifested in what we came to call the “toilet paper flower gardens” which bloomed all around national park campsites (remember- closed bathrooms). When we “friendly trespassed” on private land, whenever possible we would approach landowners to ask permission for access. In conversation these Chilean landowners expressed mistrust other Chileans using their land because of trash and abuse, but welcomed us as foreigners.

So where has this line of inquiry taken us? Those who live on the land and work it are running it into the ground. Those Chileans who would visit it, can’t afford to and when they do, they trash it. Who else is there? Foreigners. While many locals think all foreigners are wealthy, Parque Patagonia knows better.

Neon and I felt out of place sitting in the lawns of the massive buildings of Parque Patagonia Headquarters last year. It is a plot of lush green luxury in the otherwise arid Chacabuco valley. We were ushered out of the buildings because you have to take your shoes off to enter. I’m a thru-hiker, trust me, you don’t want me to take my shoes off and all I wanted was a bathroom, though I’d be just as happy peeing under this massive willow tree.

Probably because of hiker trash like us coming through last season we learned that this summer Parque Patagonia moved the campground several kilometers down the road, away from the headquarters. So, the parks and infrastructure are not for the locals, nor the average Chilean, also the cash-strapped traveler should be kept at a safe distance.

So, what “public” are these parks going to be accessible to?

I don’t have an answer for that. I’m just a dirty hiker and all I know are trails. And what I know of those are that the best maintained trails we hiked in Patagonia were the paths taken by gauchos and arrieros moving their animals seasonally across private or otherwise disregarded land. Some of the worst maintained, most overused, and grossly trashed trails were ones in national parks.

Greta corroborates, citing her own experiences:

“When we rode horseback across Patagonia, we passed through a wide variety of wild places, as well as private (with permission) and developed places. We were moving in a manner that was historically typical for the locals, but not so typical for the tourism industry. We felt the areas where the ‘way things were’ are rubbing up against ‘the way things are’, and ‘the way things will be.’

We couldn’t ride through National Parks because we traveled with dogs (which is very common for gauchos/and locals). We packed out every last piece of trash and waste we generated in the backcountry, and saw little trash in the wild places still maintained by gauchos; yet witnessed shocking amounts of litter when we rode along the Carretera Austral and along National Parks bordering the road.

Since moving to Chile several years ago, we’ve traveled through much of the country, backpacking across many of the parks, and to be frank, I haven’t seen a substantial effort throughout this country to manage parks in a progressive or sustainable way. The concept of Leave No Trace still seems to be a new one, and many parks do not have effective waste management systems or trail maintenance systems that empower visitors to get out and explore with confidence that they won’t end up lost unless they hire a guide. In many ways, we are still lacking imagination and resources.”

Of the Chileans I have spoken with about the transition of land from the Tomkins’ hands to the government, every single one has expressed reservations as to whether the government is up to the task. The comments section of a Spanish EMOL article about the matter overflows with remarks pointing to parks, airports, hospitals, all sorts of neglected projects, begun with much pomp and circumstance, which dwindled into neglect.

As we walked through the region we saw massive government billboards with a beautiful picture of what is being developed, boasting the price paid, timeline (often long since past), and construction party hired; standing over an empty lot. We’ve also moved through tourism infrastructure where you can see all the money and dreams that went into it up front, now crumbling.

This leads one to ask, why would the Tompkins opt to give the land to the Chilean government? As Kris explains in an NPR interview, “there is a sense of. . . ownership by every American who goes through the front gates of Yellowstone or Yosemite, that those are public parks. They belong to everybody. And Chile is no different. We hope that somehow between the creation of national parks, the development of what we call economic development as a consequence of conservation that precious masterpieces of the country will be preserved forever.”

The doubt I’ve heard from many Chileans and those who know the country is whether those precious masterpieces really will be preserved forever. Matias from above puts it simply, “it seems to me a gift which we Chileans do not deserve. I sincerely believe that neither CONAF nor the government know how to manage natural areas.”

In that awareness, that self-critique, I believe lies the seed of hope for the forest and wildlands and the potential for Chile’s future as a world leader in protected areas.

Potential- Where does it go from here

The Tompkins Foundation seem to be playing this one close to the chest. There is not much information out there about conditions and plans for the long term preservation of the land. This makes sense, considering they are likely in the midst of negotiations with the Chilean government.

According to an email reply to my inquiries from the Tompkins Conservation:

We are still in the initial phases of this donation process and do not have all of the terms and conditions formalized. President Bachelet and Kristine Tompkins signed a pledge for the creation of 10 million new acres of national parks in March, 2017, but the parks have yet to be formally transferred over to government control. Before this transfer takes place, the terms will be solidified to ensure a smooth transition and long-lasting protection for the lands and wildlife.

In the NPR article cited above Kris acknowledges they know there are many who are curious what is going into it but is proceeding with the deal because she believes, “Chile does have the desire to run these parks in a world-class fashion. And I think the most stable means to protect these lands is in the form of national parks.”

The closest I have found to something concrete regarding ongoing support is mention of creating a Chilean-based Friends of National Parks foundation. According to one article, “To support the government in this ambitious endeavor, Tompkins Conservation, together with key partners, is committing to creating a Chilean-based Friends of National Parks foundation for ongoing park support.” So, things are moving with hope, idealism, and a lot of positive dialogue.

This lack of information has created space for conjecture, therefore, the ideas shared in this section are just that, ideas. Hopes. The first point is, based on several of the links shared throughout the earlier sections, setting sights on the American Park system as a paradigm is to undershoot the potential for progress this could mean as a global community.

This land gift places Chile in a position to either shine or sink. Again, borrowing from Greta, “Chile is in a position to change the dynamics and bring local community impact into the conversation of local conservation efforts- they are intertwined and interwoven and inevitably impact one another.”

From this vantage point, for the long term success in both protecting the land and making it accessible to the public, there needs to be a significant component of education regarding protecting natural resources for the Chileans themselves, a way to make it accessible to those of limited resources, and a source of ongoing human and financial support for maintenance. What would be nice on top of that is some sort of project to enable those nationals who wish to pursue a responsible “frontiersman lifestyle.”

One audacious hope we might hold is that this gift and added responsibility be enough to provoke an overhaul of CONAF, if they are to be the entity responsible for the long term maintenance of these lands and resources.

Working at Philmont Scout Ranch over several years, a large reserve of private land in New Mexico held by the Boy Scouts of America, I observed the ranch operating both as a hiking destination and a working cattle ranch. So I believe there is a middle ground, a way to conserve both the landscape, people, and traditions.

Reflecting on several months of traveling on horseback through Patagonia, Greta shares an idea of how this might look,

“large scale agriculture has definitely done a number on many areas of Patagonia- and the impact of overgrazing was intense the closer we got to Coyhaique. I think the dynamic of all the other economies pushing into the region (aside from tourism) is also a point to note. What is happening in Patagonia is an opportunity for us to be creative about what happens to the people working in an industry when it is pushed out- and agriculture is a key industry to consider, as in many ways it was the easiest one for the gaucho culture to transition into.

When we were in Puerto Cisnes, I sat at the dinner table with a quiet old gaucho and tears streamed down his face as he described how deeply he longed to live as he used to, up in the mountains with his horses and dogs. He had long since lost his job on a ranch, and his family sold their land, moving them into town. Now he spent his days standing on the street looking for a daily job he could fill to cover the cost of his food. When we’d ridden into town, he rushed to us, his limp slowing him slightly, and told us we must come and stay with him on the small property outside of town that he care-took. He expressed how much he missed having a horse around, and how wonderful it was to see us traveling with a pilchero (packhorse) using traditional chiwas, as he did as a child with his parents.

I’m not advocating the large scale agriculture has to stay the way it is so people can keep those jobs; however, we are talking about a culture of people who are deeply connected with the land, losing the only option they have to be on the land when those jobs do go away. In many ways this culture is slipping away silently.

When we arrived in Coyhaique we stayed with a friend who had bought 1000 hectares of very damaged, overgrazed land and began managing it using holistic ranch management methods with intentional grazing rotation. They are members of the group Ovis 21, who despite receiving some negative press from a narrowly focused PETA campaign a few years ago, has actually had a hugely positive impact on the health of the land where the ranch management techniques are applied. We witnessed this impact, noticing how damaged all of their neighbors lands were while our friend had pastures that were resilient and lush. This is more than an ‘all or nothing’ conversation- we can be dynamic in the way we preserve and nurture wild places and local cultures. “

Another iteration of what this could look like, of involving locals and engaging their skillsets and know-how, was a highlight in our first four months of walking. We had hiked through the popular trails of Cerro Castillo and arrived at the northern edge where there was only one official trail out. Yet, we had beta on a now defunct CONAF trail. None of the park guards posted at the vehicle entrances had knowledge of the area (as they were from other parts of the country) or even knew of the existence of that trail.

It was to our delight that the backcountry outpost from which we sought to launch the exploratory route happened to be manned by Juan, a gentleman who had lived in the campo outside of the town of Cerro Castillo his entire life. As had his parents and grandparents before them. Once we made it through the initial, “no, you can’t go that way. It is closed,” once we saw we had the same information, he became excited and quite open. Sharing everything he had heard of this “once upon a time trail”, indicating the logging roads which would get us there, and warning about the landslide area.

We conversed late into the evening and he shared that he was delighted to have this job, that it was almost by a fluke that he had landed it, as it is very hard for people of low education to get a CONAF position and that most people from the campo can barely read. He professed a dedication to his work, to protecting the land and to holding his job with a tenacity I have rarely seen in park employees anywhere in the world. While he had to use his finger and mutter the words to himself, I watched entranced from the loft as he read by candlelight into the night.

There does exist a middle ground between shunning the poorly educated locals, keeping them and their animals off the land and maintaining an inviting and healthy ecosystem for visitors to get to know. Finding and maintaining that balance will take a lot of work.

There is a lot of positive dialogue happening, and only by giving air to the concerns can we move forward with a complete perspective, in a hopeful direction. In the words of our conservationist friend:

“I have seen a lot of conservation projects all over the world in my career, and I can honestly say that theirs [The Tompkins’] is the most impressive I have ever seen. Everything they do is exceptionally executed with amazing ambition and vision. Overall, I think that their gift is truly a transformational act of generosity and conservation.

. . .

And yes, the Chilean Gov’t did originally agree to the dams, and the Tompkins fought like crazy against them. But I think that that the Tompkins also believe strongly that there are many ways of bringing governments around to doing the right thing. And securing this amazing land match represents a huge breakthrough.”

While the idea of the move is a positive one and received a lot of such attention from the international press, the idea does not define the outcome. That will be determined by the execution and there is precious little information on how that has been/will unroll. I think many of us who have been watching, like Greta, “wish there would have been more actual coverage of the state of the park system here in Chile, and how this will improve how the parks are run or influence that in any way.”

I believe it falls to those who regard this massive move with a critical eye. Not critical in being negative, but rather, objective analysis and evaluation to form a balanced judgement. We can celebrate that this is an unprecedented gift but that also means there will have to be unprecedented effort and structures to make it work and there is not much history or foundation for that and relying on models by countries such as the United States stunts potential from the get-go.

Fortunately, there are people like Greta, Matias, Marcela, Coce, and hundreds of others, who think and live differently. These people stand out and are in the minority, so tapping their wisdom and perspective is crucial to unrolling this in a way which will bring about a positive outcome.

For example, I again turn to Greta:

“I’m brewing up a project down here that is digging into the root of what it would actually take to preserve and conserve large swaths of land/wild places while also supporting local cultural preservation and engaging visitors, and the local community, to be in relationship with the land – through story and curiosity- rather than the typical exploitative or extractive experience of

‘I’m here because I need to get my Instragram photo with the towers.’

Taking a look at access from the perspective of how we can inspire people to be curious and respectful, rather than just giving them some ecological/naturalist facts and rules to follow- we need to create an environment of real connection and relationship with nature. That is the goal. We need to consider the role parks and preserved lands play within the ecosystem of the place they inhabit- they are part of a larger ecosystem after all, one that includes communities and industries and economies. They’re all interconnected, so we have to consider how they are impacting one another, and how this impact can be positive and regenerative. . . . But we’re still in the midst of a long journey. We can do better, we can always do better.”

Yes, we can do better and I believe we must. If you have the curiosity and follow through to have made it through this piece, you hold the promise of the future. Apply that to watching this matter, as information trickles out. Follow up from time to time. Be conscientious and inquisitive when you come to Patagonia. Best of all, be active in the Conservation efforts around your home.

In conclusion, what the Tompkins have done by gifting this land to Chile is a first leap toward unknown potential. Whether and how we as a global community and Chile as a nation and individuals handles this will be the determining factor of the long term effects. The Tompkins have been clear about their intentions. Now it is time for each of us to determine ours.

Massive thanks to Greta for giving me the fodder to write this piece, contributing, and corroborating throughout the entire process.

Thank you to Matt for asking the questions and having the curiosity. To my hiking partner for being patient as I type loudly into the night while camped in the field and push into towns to get electricity and connection to work further. To the dozens of voices from across Patagonia who replied to my inquiries and shared their insights and experiences.

It has only been with a great deal of input, advice, resources, and patient editors that this piece is as it stands. I hope it does you credence because each of you are who I aspire to live up to. It is the combination of your insight, hope and humility which drove me to seek your insight and I cannot thank you enough for all you give.

Further Learning:

“The Diverse Properties of Private Land Conservation in Chile: Growth and Barriers to Private Protected Areas in a Market-friendly Context” by: David R Tecklin, Claudia Sepulveda

Comments (9)

Thanks for this enlightening and informative article. , Cliff and Martha Rawley

It means so much to me that you follow our journey and read what we write.

Thank you Cliff and Martha!

Excellent work. Thanks for writing it.

Thank you so much, Jon!

This is so great! Thank you for all the hours you must have poured into this. I linked it to the Field Notes page that accompanies your podcast. http://www.boldlywentadventures.com/field-notes-23-her-odyssey.html

Great piece. You hit on so many of the experiences and reflections that Lydia and I collected during our traveling. There are many things that I would like to share. We too came up with the name “brown town” for the TP “gardens”. We were told, “No, you can’t go there,” so many times we just stopped asking. At least half or more of our time was concentrated in the wild areas where there were no trails. This was mainly because the few trails that did exist were overcrowded or trashed or mud pits. There is much to share. Lydia and I will discuss and organize some good insight (hopefully). I do share your concern for the management piece. Just go backpacking to the mirador de Torres in Torres del Paine and you will find the makings of a future cholera outbreak. More to come.

I look forward to hearing more thoughts. Affirming also that other insightful travelers to the region see and know the same. We had a good chuckle about “brown town” over dinner!

thank you for taking the time to write this thoughtful essay. I see there is a lot of detail that needs to be worked out to ensure Patagonia remains wild and it’s not just a matter of the Tompkins conveying their land to the government. It’s a complex issue and it was heartbreaking to learn of how ranchers are being forced out of their generational land under the banner of conservation.

Thank you for reading through it. Those realizations you talk about having are what give writing like this a purpose!