The ‘Herstory: She Can’ series profiles women who pursue their passions. Each have stepped up with courage, a message, and a willingness to share her own odyssey.

The specific weight of the soul is equal to the sum of what has been dared.

~Bert Hellinger

A sewing machine and life jackets helped fund the wing where we sleep in Alejandra and Koky’s house. “This place has always been our refuge.” The home among the cliffs above the lakeside village of Potrerillos is tidy and classy but rooted in a fierce and unruly will. It is the hub from which their journey these past 25 years has spooled.

There is a playfulness about the house; antique sewing machines stuck to the wall, alpine magazines scattered around, the enviable gear closet, a trailer of kayaks and life vests in the yard, ample places to crash and, not least of all, their willingness to open their refuge to two weary strangers. I pass a drizzly afternoon shuffling through a trunk of photographs which ties the story together. While everything has the veneer of maturity, these are clearly River Rats, grown up.

At some point Alejandra realized, “rebellion had been the motor of my life.” If she was told not to or that she couldn’t do something, she was all the more driven to it. She ties it to growing up as as an only child of a single parent. Her father died when she was young, so she says she grew up more independent than most other girls. “You see, dads are usually the one to take their daughters places but my mother told me ‘you have to get yourself places but I want to always know where you are.'” she explains.

As a young woman, she traveled to the United States by herself to learn English in an immersion course in California. She recalls the time spent studying amidst people from all across the globe but points out, everyone was there on their own mission. There was not the sense of community and collaboration which pervades her native Argentina.

She spent another year living in San Luis, Argentina. Again, away from what she knew. She was working several jobs, and the friends she did hold were also ambitious and worked a lot. This made finding time together difficult. She recalls with a smile that one friend’s job involved driving around the city, so, on the rare occasions that she had time off, she would fill up the mate termo (the ubiquitous hot water thermos for drinking mate) and hop in the truck, and they would drive around and chat.

“But I was not happy there,” she noted, “it was hard and I gained a lot of weight because I was so unhappy.” This affirmed that Alejandra needs physical activity, as reflected by her jobs, which have ranged from gardening to physical education.

In 1993, she was working at a program in Mendoza to get kids adventuring. That was where she met Koky, a climbing instructor. Within a week they were living together. In less than a year, they were married.

“Our wedding was very simple,” she explains. Neither of them were much interested in the whole affair but their families insisted. “As soon as we walked out of the church, we took off the suits and rings.”

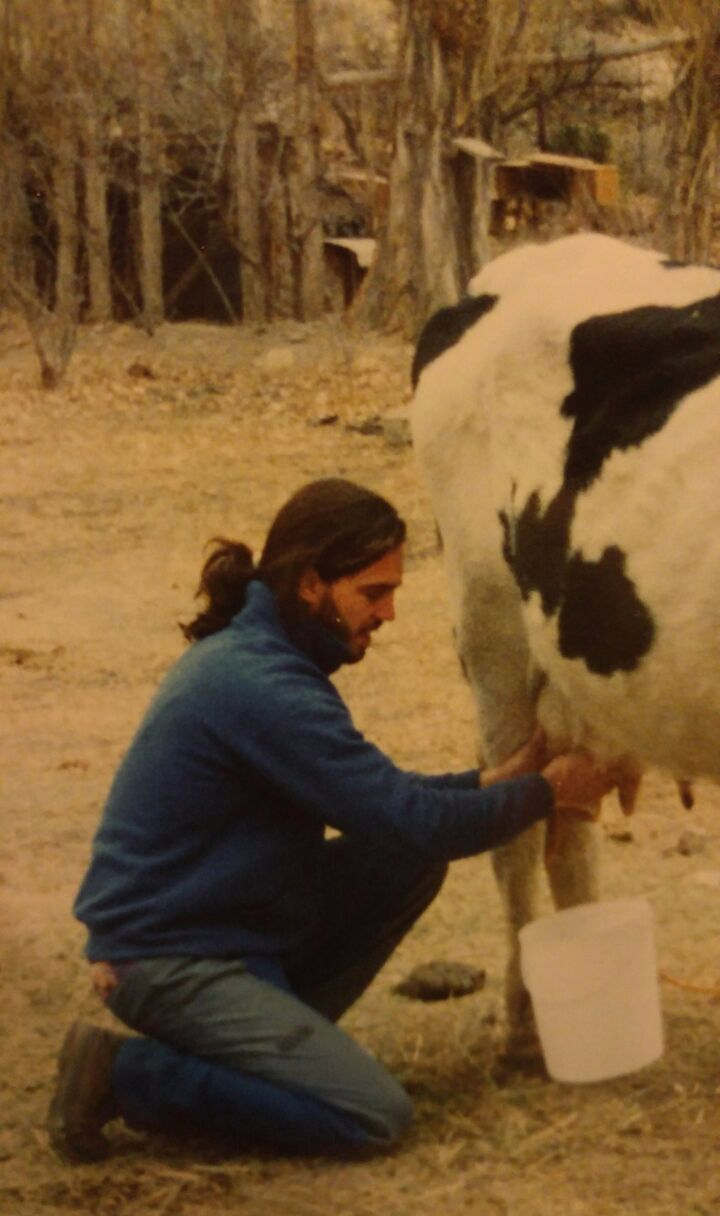

As a wedding gift, her mother gave them a carpeta (downpayment) on a town-home. They traded it in for this land, which was a potrero (strip of pasture land) with a ratty cabin on it, where they kept a cow and various other farm animals.

She remembers those early and lean days fondly. When they were so broke the relied on the cow for food. “We had milk, yogurt, cheese.” Sometimes more than they knew what to do with, so they did what any good Argentine does, they put a sign at the end of their driveway and began selling milk at a fraction of the cost charged at the grocery store.

Around that time Koky, an avid kayaker, came home from a river trip in Costa Rica with a used PFD (personal flotation device), but the material on the outside was not very good. Alejandra, who had learned how to use a sewing machine from her mother, made a pattern and “it came out alright,” she shrugs.

The evolution of their relationship is tied up in the story of their business. In Argentina in 1993, there were no imports, so everything was very expensive and the river rafting niche was quite small. “Soon friends started asking for a PFD, then the rafting companies, who had to import PFDs needed them, and that was how Bio Bio got started.”

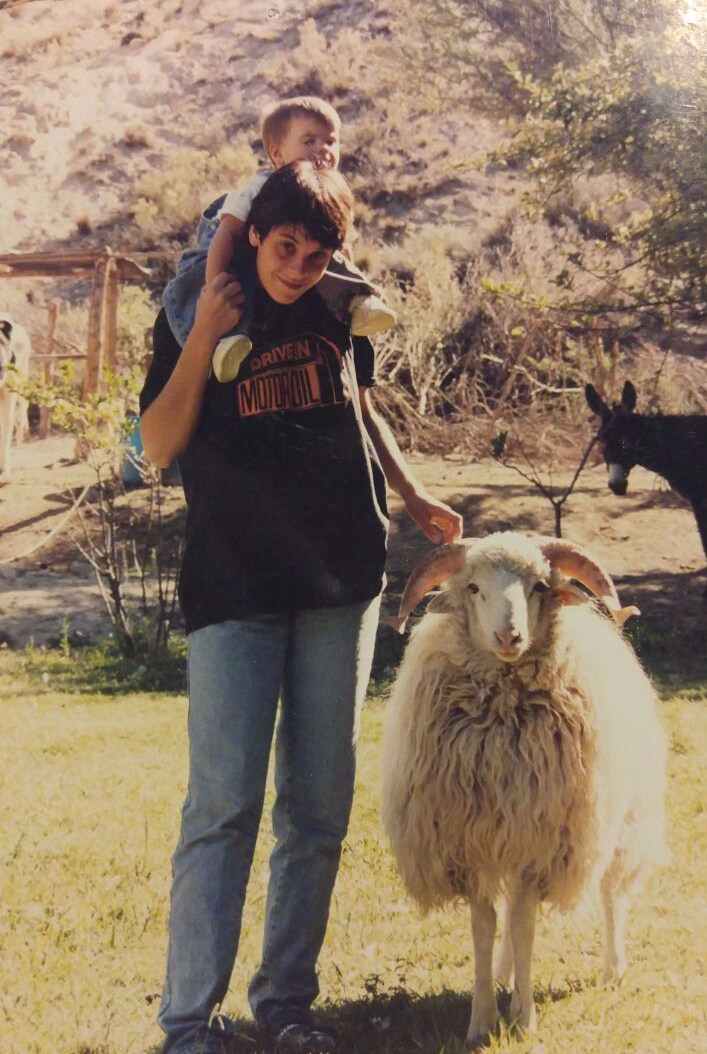

The same year they were married, Bio Bio Indumentaria Deportiva was born. Less than a year later came their first daughter. The next year, their second. “Bio Bio was our first child,” Koky lights up. “Now it is grown and rebellious but it enables us to work to live, not the reverse.”

“When we fought he would go to work,” Alejandra explains. “I did not understand that to him the business was like a child which I was abandoning.” The couple, like their business, have hit some rocks and been through more than a few strainers but they are certain together when Koky says, “we are entrepeneurs, not business people.”

In the early years they navigated a precarious economy, personal lack of finances and struggled to find skilled labor, starting a family, a lot of fighting, and an unreliable vehicle. The one guy who they found who could sew well lived a season in a tent in their yard. The car they had “would break down often and you’d have to push it” Alejandra recalls. “The brakes were tricky to so you had to be tapping them the whole way down to Mendoza. It was an adventurous and exciting season [etapa] of life.”

The couple discuss living a parenting role reversed from the Latin paradigm. “He is very sensitive and more family oriented, traits which most people would say are feminine. I am more detached [despegada] and practical.” Alejandra states, matter of factly. She is exceptionally direct and Koky recalls, “when she would come in to the business,” which after some years had established a workshop and number of employees, “people would start sewing badly and messing things up because they were so nervous of her looking over their shoulder and criticizing them.”

“I had no idea,” Alejandra shrugged and chuckled, looking back now, “I just thought they were that bad all the time!”

Around 2005, everything went to pieces. Their daughters were teenagers, her mother was dying, their relationship was on the rocks, the Argentine economy was in yet another crisis. They divorced. She describes it the period saying, “I fell down completely. My boat turned over and I sank to the depths of the Ocean.”

“Everything has its before and after,” she continues. Pulling out of it took therapy, salsa classes 3 days a week, meditation and a practice called “Family Constellations.” This process, established by Bert Hellinger, helped her move forward.

Now Alejandra and Koky are remarried and living in their mountain refuge. Each morning they commute the 70 km down to Mendoza where she teaches in an elementary school and he manages Bio Bio.

“You have to believe or burst,” she says. From the tumult of their separation she learned that your partner holds up a mirror, sometimes reflecting your least favorite features.

“Whatever characteristic you most resist in yourself, once you accept it, it loosens its grip on you.” She came to recognize that she is a detached [desapegada] and anxious person. In confronting these things, she has realized that anxiety is a manifestation of unrecognized fear. “Koky has taught me the value of family.” She smiles across the table at him. She has resumed taking dance classes.

Comments (1)

What a good story of soul journey, learning, and hard work leading to wise partnership! What inspiring people you are graced to meet on your long walk.