Haz clic aquí para leer en español

Written by Fidgit

I am by no means a health or nutrition person. I love sugar and all things unhealthy, I try to get as many calories as possible when long walking and that is about the extent of it. This is to say, It takes a lot to get me to notice nutritional health issues. Walking across Bolivia we not only witnessed but experienced the effects of lack of basic and essential dietary needs.

One Country Study on poverty and malnutrition in Bolivia (World Bank, 2002) states “Malnutrition afflicts about one fourth of children under three years of age and between 12 and 24 percent of women in Bolivia. It contributes to high death rates, immune

deficiency, learning disabilities, and low work productivity.”

A later section of the study, “Myths of Malnutrition” goes on to state, “Debunking myths about the causes of malnutrition is also important. The dominant misconceptions are that malnourishment stems from: (1) food scarcity and a lack of self-sufficient farming, (2) lack of milk and meat, (3) high altitude, or (4) genetics.”

While their reasons stand, as these factors are not “causes” I argue that several contribute significantly. Some of which we became aware were: poverty, elevation, food preperation, and a lack of awareness about nutrition.

Let’s work our way down this list.

Poverty

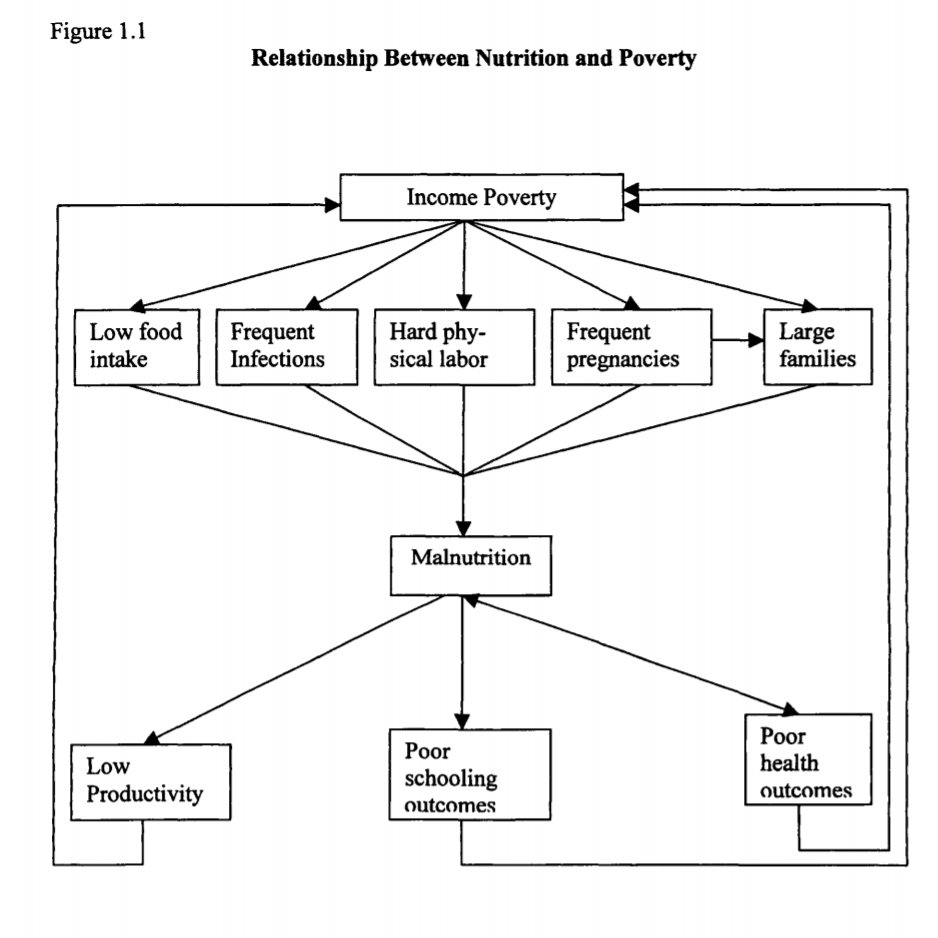

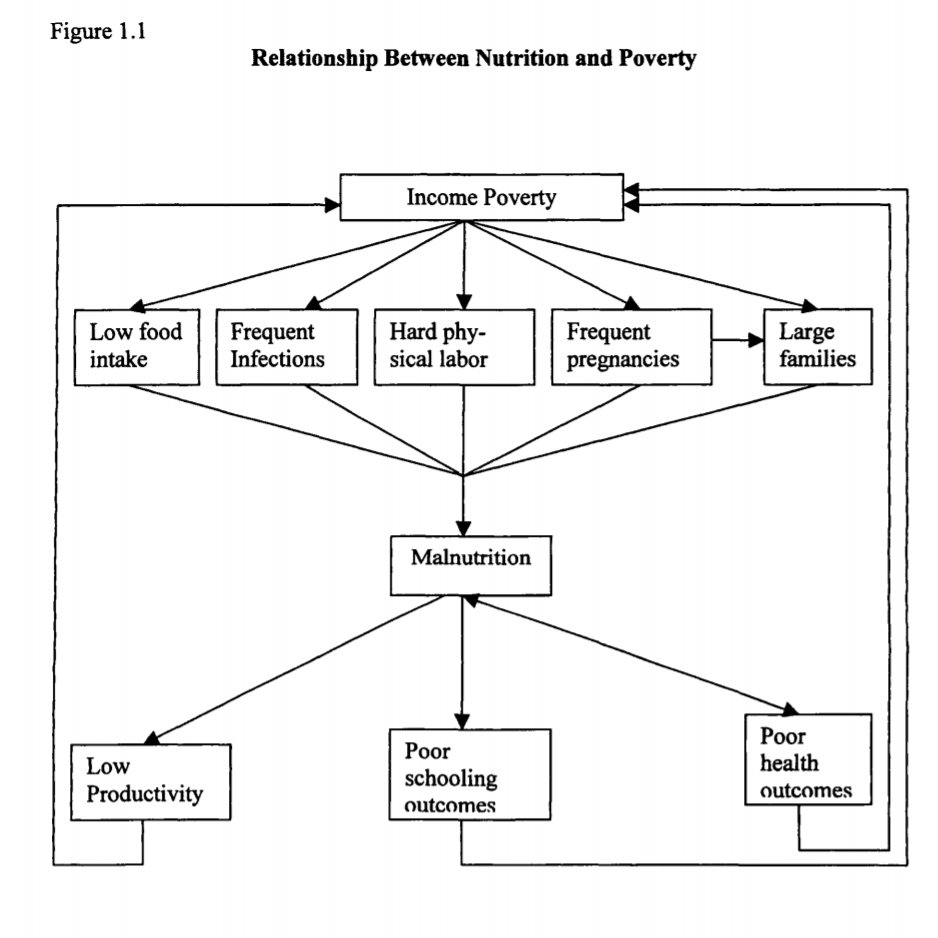

One point on which I think we can agree is that poverty is clearly a factor in the effects of malnutrition with which many Bolivians contend. One figure from the study laid out the interplay nicely:

An example of the privilege we have is that the effect of the nutrition issues on us were largely: observing those who lived with it and our experiencing temporary physical set backs.

At the end of conversations I would sometimes ask the kids how old they were and they always reported being 3-4 years older than what I would have guessed. The largest body of evidence I saw was talking to a school of 50 kids ranging from 5-12. Each grade appeared significantly younger than if they had been lined up next to, say, the Argentine schools we’ve talked at. Children are older than they appear, women were younger than they appear.

When the effects of making this diet a practice began to affect us we were able to offset it by taking transport to larger well supplied cities every few weeks to stock up on nutrient rich basics and vitamins. One area in which we suffered significantly and consistently was from the water, which wreaked havoc in our intestines and stomachs. Cramping, protracted bouts of diarrhea, all the fun stuff.

Elevation

The study cited above argues that elevation is not a factor in malnutrition because of misplaced belief that greater altitude stunts children’s growth. While I agree with this, our experience as travelers through the highest and most isolated country in South America is that elevation has other effects.

We entered from the south at about 11,000 ft and left out the north at about 15,000 ft. The lowest we dropped to was around 9,000 ft. The first month we were lightheaded, dizzy each time we stood up, reduced muscle response to commands, and having to stop or slow often to breathe.

Another, unanticipated effect of the elevation, was that healing was dramatically slowed. About a month in and we were both going through rounds of illness ranging from dehydarrhea (my new favorite hiker word, as coined by Drag Man from the GPT and very accurate to the symptoms), fever, weakness, aches, etc. We also noticed simple things like cuts, split lips, etc took longer to heal.

Another effect of the elevation is persistently lower temperatures which affects the capacity for growing food.

Food Prep and Growth

The World Bank’s study cites, “Insecurity of the food supply is often held up as the chief cause of malnutrition in Bolivia (CEESA, 1997). . . . In reality, fairly recent data (1999) suggest that total food availability is 2,237 calories per person per day, an amount adequate to feed the population if distributed equally (FAOSTAT, Sept. 12, 2001).”

One frustration we had was that almost all of the cheap food was fried. Primarily it was fried in vats of obviously very old and low quality oils. In some regions pollo a la brassa (rotisserie chicken) was prominent and delicious but relatively expensive. Besides that the main meat was llama, whose health benefits were widely professed but also non-specific. They all told us llama meat was healthy, no one could explain why.

Most of the regions through which we traveled were dry, the soil was semi-arid at best, while prolonged cold temperatures and deep frosts limited growth periods. The land was largely used for llama grazing. If you are fascinated by soils, this is a good read. The planting we saw and talked with people about were: lima beans, quinoa, and potatoes. Not just plain, low value Yukon Golds, but a cool and crazy variety of potatoes from ancient lines.

So, I agree with the first point of the Nutrition Myths made by the World Bank study but if, even with growing season and capacities limited, they are able to grow such super power foods, why the malnutrition? The study offers interesting research which I encourage you to read. My experience, living out of a backpack in the field, limited my information gathering capacity to asking around.

I asked dozens of Bolivians this question.

Awareness

“The price of our quinoa has dropped by 400%,” Naomi laments. Her family and entire community subsist on quinoa crops, “the people can’t even afford to buy rice at the shops!”

“Why don’t they eat the quinoa?” I ask.

“Because that is for export. If we don’t sell it we don’t get money. I hear people in China will pay a fortune for just a handful of quinoa but we make almost no money from selling it.”

“People pay a lot of money for quinoa because it has a lot of good nutrients and calories,” I explain, “In the United States we call it a super food’.”

“Then we should be paid more for it, then we could afford rice!”

“But if you are not able to sell it for a fair profit, why don’t you eat it yourselves?” I press.

“Because,” I can sense she is frustrated, that I am missing some link in her line of reasoning, “it is for export.”

The dissonance of this conversation has become familiar. Some say their grandparents ate it, others say it was for the animals. There seems a hint of prejudice against quinoa as a food for the very poor, even if they know it fetches a high price in foreign countries. The shop owners I’ve asked say no one buys it, that people want bleached rice and pasta instead, so they don’t sell it. This strikes me as a lack of understanding for the true wealth of the ubiquitous grain.

The small, one room or even closet size shops in most of the villages sell almost exclusively empty carbs: crackers, juice mixes, puffed cereal, Coka Quina (the national soda), “chocolate flavored” wafers, and mayonnaise. Bottles of 96% denatured alcohol (which we use for our stove) which is consumed as a beverage is in every shop.

We found quinoa only in La Paz, and a few towns as a pre-packaged “for distribution” good. Dried lima beans are also common when we found bulk sales shops (semi-regularly), and potatoes were also eaten as a staple.

In terms of what foods are available for purchase in the shops, the Bolivian altiplanos are a food desert beyond almost anything I have seen in the US. Therefore, basic and important nutrients come from what people can produce. I believe the gains they and their children would experience from directly consuming what they grow far outweighs the pittance they are paid for selling it but many fail to grasp this. Entrenched in poverty, immediate gains are always more pressing and evident than long term returns.

We tried to proliferate the values of the foods right under their feet but this is a matter requiring much more education, challenging of prejudices, and fostering opportunity than we were able to provide.

Though, I do hope we planted some seeds. . .

Bolivia: las montañas como un desierto de alimentos

Escrito por Fidgit

Traduccion por Henry Tovar

De ninguna manera soy una persona de salud o nutrición. Me encanta el azúcar y todas las cosas no saludables, trato de obtener tantas calorías como sea posible cuando estoy caminando mucho y eso es todo. Es decir, se necesita mucho para que note los problemas de salud nutricional. Caminando por Bolivia no sólo presenciamos, sino que experimentamos los efectos de la falta de necesidades alimentarias básicas y esenciales.

Un estudio de país sobre la pobreza y la malnutrición en Bolivia (Banco Mundial, 2002) afirma que “la desnutrición afecta a alrededor de un cuarto de los niños menores de tres años y entre el 12 y el 24 por ciento de las mujeres en Bolivia.

deficiencia, problemas de aprendizaje y baja productividad laboral “.

Una sección posterior del estudio, “Mitos de la malnutrición” continúa afirmando: “Desmitificar los mitos sobre las causas de la desnutrición también es importante. Los conceptos erróneos dominantes son que la desnutrición proviene de: (1) escasez de alimentos y falta de autosuficiencia agricultura, (2) falta de leche y carne, (3) gran altitud, o (4) genética “.

Si bien sus razones son válidas, ya que estos factores no son “causas”, argumento que varios contribuyen significativamente. Algunos de los que nos dimos cuenta fueron: pobreza, elevación, preparación de alimentos y falta de conciencia sobre la nutrición.

Vamos a trabajar en esta lista.

Pobreza

Un punto en el que creo que podemos estar de acuerdo es que la pobreza es claramente un factor en los efectos de la desnutrición con la que muchos bolivianos sostienen. Una figura del estudio planteó la interacción muy bien:

Un ejemplo del privilegio que tenemos es que el efecto de los problemas de nutrición en nosotros fue en gran parte: observar a aquellos que vivían con él y experimentar retrocesos físicos temporales.

Al final de las conversaciones, a veces les preguntaba a los niños qué edad tenían y siempre me informaron que tenían entre 3 y 4 años más de lo que hubiera imaginado. El mayor cuerpo de evidencia que vi fue hablar con una escuela de 50 niños que iban de 5 a 12. Cada grado parecía significativamente más joven que si se hubieran alineado al lado de, digamos, las escuelas argentinas en las que hemos hablado. Los niños son más viejos de lo que parecen, las mujeres eran más jóvenes de lo que parecen.

Cuando los efectos de hacer de esta dieta una práctica comenzaron a afectarnos pudimos compensarla llevando transporte a ciudades más grandes y bien abastecidas cada pocas semanas para abastecerse de nutrientes básicos y vitaminas. Un área en la que sufrimos significativamente y consistentemente era del agua, que causó estragos en nuestros intestinos y estómagos. Calambres, ataques prolongados de diarrea, todo lo divertido.

Elevación

El estudio citado anteriormente argumenta que la elevación no es un factor en la desnutrición debido a la creencia errónea de que una mayor altitud impide el crecimiento de los niños. Si bien estoy de acuerdo con esto, nuestra experiencia como viajeros a través del país más alto y aislado de Sudamérica es que la elevación tiene otros efectos.

Ingresamos desde el sur a unos 11,000 pies y dejamos el norte a unos 15,000 pies. Lo más bajo que caímos fue alrededor de 9,000 pies. El primer mes estábamos mareados, mareados cada vez que nos ponemos de pie, reducimos la respuesta muscular a los comandos, y tener que parar o reducir la velocidad a menudo para respirar.

Otro efecto imprevisto de la elevación fue que la curación se redujo drásticamente. Alrededor de un mes y ambos estábamos pasando por una serie de enfermedades que iban desde la deshidroterapia (mi nueva palabra favorita para excursionistas, acuñada por Drag Man del GPT y muy precisa para los síntomas), fiebre, debilidad, dolores, etc. También notamos cosas simples como cortes, labios partidos, etc. tomaron más tiempo para sanar.

Otro efecto de la elevación es la persistencia de temperaturas más bajas que afectan la capacidad de cultivo de alimentos.Preparación de alimentos y crecimiento

El estudio del Banco Mundial cita: “La inseguridad del suministro de alimentos a menudo se considera la principal causa de malnutrición en Bolivia (CEESA, 1997) … En realidad, datos bastante recientes (1999) sugieren que la disponibilidad total de alimentos es de 2.237 calorías por persona por día, una cantidad adecuada para alimentar a la población si se distribuye por igual (FAOSTAT, 12 de septiembre de 2001) “.

Una frustración que tuvimos fue que casi toda la comida barata estaba frita. Principalmente fue frito en cubas de aceites obviamente muy viejos y de baja calidad. En algunas regiones, el pollo a la brassa era prominente y delicioso, pero relativamente caro. Además de que la carne principal era llama, cuyos beneficios de salud eran ampliamente profesados, pero también no específicos. Todos nos dijeron que la carne de llama estaba sana, nadie podía explicar por qué.

La mayoría de las regiones a través de las cuales viajamos estaban secas, el suelo era semiárido en el mejor de los casos, mientras que las temperaturas frías prolongadas y las heladas profundas limitaban los períodos de crecimiento. La tierra fue ampliamente utilizada para el pastoreo de llamas. Si le fascinan los suelos, esta es una buena lectura. La plantación que vimos y conversamos con la gente fue: habas, quínoa y patatas. No solo el Yukon Golds simple, de bajo valor, sino una variedad fresca y loca de papas de líneas antiguas.

Por lo tanto, estoy de acuerdo con el primer punto de los Mitos de la Nutrición realizados por el estudio del Banco Mundial, pero si, incluso con el crecimiento de la temporada y las capacidades limitadas, son capaces de cultivar tales alimentos súper poderosos, ¿por qué la desnutrición? El estudio ofrece interesantes investigaciones que te animo a leer. Mi experiencia, vivir de una mochila en el campo, limitó mi capacidad de recopilación de información para preguntar.

Le pregunté a docenas de bolivianos esta pregunta.

Conciencia

“El precio de nuestra quinua se ha reducido en un 400%”, lamenta Naomi. Su familia y toda la comunidad subsisten con los cultivos de quinua, “¡la gente ni siquiera puede permitirse comprar arroz en las tiendas!”

“¿Por qué no comen la quinua?” Pregunto.

“Porque eso es para exportar. Si no lo vendemos, no obtenemos dinero. Escucho que la gente en China pagará una fortuna por solo un puñado de quinua, pero casi no ganamos dinero vendiéndola”.

“La gente paga mucho dinero por la quinua porque tiene muchos nutrientes y calorías buenos”, le explico, “en los Estados Unidos lo llamamos un súper alimento”.

“Entonces deberíamos pagar más por ello, ¡entonces podríamos comprar arroz!”

“Pero si no puedes venderlo por una ganancia justa, ¿por qué no te lo comes tú mismo?” Yo presiono.

“Porque”, puedo sentir que está frustrada, que me falta un eslabón en su línea de razonamiento, “es para exportar”.

La disonancia de esta conversación se ha vuelto familiar. Algunos dicen que sus abuelos se lo comieron, otros dicen que fue para los animales. Parece haber un prejuicio contra la quinua como alimento para los muy pobres, incluso si saben que tiene un alto precio en el extranjero. Los dueños de las tiendas que les pregunté dicen que nadie lo compra, que la gente quiere en cambio arroz blanqueado y pasta, para que no lo vendan. Esto me parece una falta de comprensión de la verdadera riqueza del grano omnipresente.

Las tiendas pequeñas, de una habitación o incluso de tamaño de armario en la mayoría de los pueblos venden casi exclusivamente carbohidratos vacíos: galletas saladas, mezclas de jugos, cereal inflado, Coka Quina (soda nacional), obleas con “sabor chocolate” y mayonesa. Las botellas de alcohol desnaturalizado al 96% (que utilizamos para nuestra estufa) que se consumen como bebida se encuentran en todas las tiendas.

Encontramos la quinua solo en La Paz, y unas pocas ciudades como un bien preenvasada para la distribución. Los frijoles lima secos también son comunes cuando encontramos tiendas de venta al por mayor (semi-regulares), y las papas también se comen como un alimento básico.

En términos de qué alimentos están disponibles para comprar en las tiendas, los altiplanos bolivianos son un desierto de alimentos más allá de casi todo lo que he visto en los Estados Unidos. Por lo tanto, los nutrientes básicos e importantes provienen de lo que las personas pueden producir. Creo que las ganancias que ellos y sus hijos experimentarían al consumir directamente lo que cultivan supera con creces la miseria que se les paga por venderlo, pero muchos no logran comprender esto. Atrapados en la pobreza, las ganancias inmediatas son siempre más apremiantes y evidentes que los rendimientos a largo plazo.

Intentamos proliferar los valores de los alimentos directamente bajo sus pies, pero este es un asunto que requiere mucha más educación, un desafío a los prejuicios y una mayor oportunidad que la que pudimos brindar.

Sin embargo, espero que hayamos plantado algunas semillas. . .

Comments (9)

wow, this is really sad news. the societal collapse reaches so far – and the brainwashing of innocents is complete. all for the sake of a dollar – have you read any of the hopi prophesies? this type of scenario is definitely touched upon. life out of balance and the final phases of mankind as we know it. glad you were able to [hopefully] “plant some seeds” 🙂 i pray these people survive.

I have not read hopi prophesies. Is there a book title I can look up?

I really enjoyed this podcast talking about hedonistic substances and how, basically the best thing we can do for social and physical long term health is sit down to a homemade meal together: https://www.ft.com/content/7af80630-c1a6-4833-9f39-dae093b348d3

The way we all did at the yurt. =)

About 12 years ago I traveled in Bolivia with a backpack but not hiking. I traveled by bus, Toyota Land Cruiser, and train. Unfortunately I did not meet many people and get to know them as you have done. I did however have quinoa in Uyuni and in southern Bolivia. Quinoa has become much more well known and popular in the US since then. The people who prepared and served it topld of its nutritive value. It sounds like now quinoa is little used as a food source in Bolivia. Things change.

Oh I so wished to try out the trains! The tracks in Argentina and Chile are mostly decommissioned but I like that Bolivia still use theirs.

One evening we were night hiking between Uyuni and Patambuco around 10 pm and hopped off the tracks to watch a train pass and looking in at the passengers staring out into the night, not knowing we were standing right there.

…jeeze. I love trains.

Thanks for the valid insights about nutrition issues in Bolivia. The poverty and poor nutrition are so hard for the people there.

Thank you for your thoughts, Cliff.

It is always so encouraging to hear from steady followers.

Pingback: Economics of a ‘Bolqueo’ – Her Odyssey

Pingback: Meet the Women Behind Her Odyssey - The Trek

Pingback: Meet the Women Behind Her Odyssey – The Trek – MC Studio