Haz clic aquí para leer en español

Written by Fidgit

Crossing Bolivia we found only a few trails, some back roads, a lot of railroad, and a long stretch along Ruta 1 from Uyuni to La Paz, so not much navigation was required. After the “brain drain” we experienced in the first season of walking, my perspective on using audio devices while hiking shifted, and my little mp3 device has become a regular piece of kit. Along this stretch, I kept my mind engaged and fed with podcasts.

Walking these more populated routes, we also encountered ramifications of the pervasive practice of public protests, often taking the form of ‘bloqueos,’ wherein roads are closed by demonstrators. The first one was nerve wracking, as we were uncertain what was going on and had heard of these events turning violent. Then they became an interesting event to observe, then they became mundane and something of a nuisance. We came to call them “protests Mondays,” though they were possible any day of the work week.

So when the Freakonomics podcast episode “Do Boycotts Work?” came into my ear holes, I perked right up and began to observe the bloqueos with more scrutiny. What follows are some observations.

Who is Protesting, and How

We treated these gatherings with caution, as there is always a chance – and also a history – of violence erupting when large groups gather to demonstrate displeasure. Fortunately, every protest we encountered was peaceful, if confrontational; and as one driver complained, in La Paz, “always at least one district is closed due to a bloqueo.” While we were there, the roads in our district (Distrito Sur) were closed for at least four days. Every afternoon on the news, there were reports of where there had been protests that day. A travel advisory, of sorts.

Interestingly it seemed primarily to be women populating the protests. They would come out in the early mornings, hang banners and ropes across intersections, and then post up in groups, sitting in circles chatting and knitting in the middle of the road, umbrellas or sombreros protecting them from the sun. The women here seem always to be knitting, though some crochet.

Men, while far fewer in number, were generally engaged in active or leadership positions. Pushing rocks up onto the roads, wandering through the crowds giving impassioned speeches, standing in positions where conflict is likely, or drinking in the shade of buildings around the periphery.

Why/What is being protested

Generally, the motivator is financial, though sometimes social reasons were cited. Often, it is because they are being charged money they don’t want to pay or aren’t getting money they think they should: a three percent raise of the electric bill in Oruro, the release of prisoners in La Paz, a neighboring district getting more money than them from the tourism industry.

A fair number of the individuals, when I asked what they were protesting, either refused to answer (or even look at me), did not know what was being protested, or cited different motivators than others in the same demonstration. This occurred in the larger cities. When I asked other Bolivians not involved in the protests, there was a sense that many who show up to these protests are of lower means, education, and awareness and come out because of social pressures rather than information.

Other times, it was smaller communities gathered together, stopping traffic at the bridges and accepting money for vehicles to pass. We passed by one like this in a village on the highway outside La Paz. At the bridge we approached, there was a neighborhood man strutting around importantly, looking very official with a pink school notebook writing down I’m not sure what, but he seemed to be accepting payments from mini drivers for permission to slip past. Three times the drivers paid him and each time he accepted, then when heckled by a group of women standing on the far side of the bridge he refused the payments and gave the money back.

Eventually, one white van went creeping out past the edge of the town, drove through the dry river bed out in the middle of the salty, dusty pampa and took off on the other side. As soon as everyone saw his plume of dust, all the vehicles tore off in that direction. Buses, semi-trucks, glossy city vehicles, all weaving and bumping around. It was an impromptu rally race, with convoys of unaffiliated vehicles following one another, navigating seemingly at random.

Immediate Financial Impact

Word spreads quickly when there is a bloqueo. So a lot of the minis, a primary source of public transportation, simply don’t drive that day, or they drive different routes. The guy who is still willing to drive it raises the price. In all fairness, he is going to have to find a way around which means more time, wear on his vehicle, and fuel (though this price is subsidized by the government).

There is the bribery mentioned above. Though, one must not call it bribery. Most not involved in the protest seem to view it more as a “pain in the ass tax.” At the village bloqueo mentioned above, as we watched the drivers and man on the bridge haggle Neon observed, “this is more like a neighborhood fundraiser than anything.”

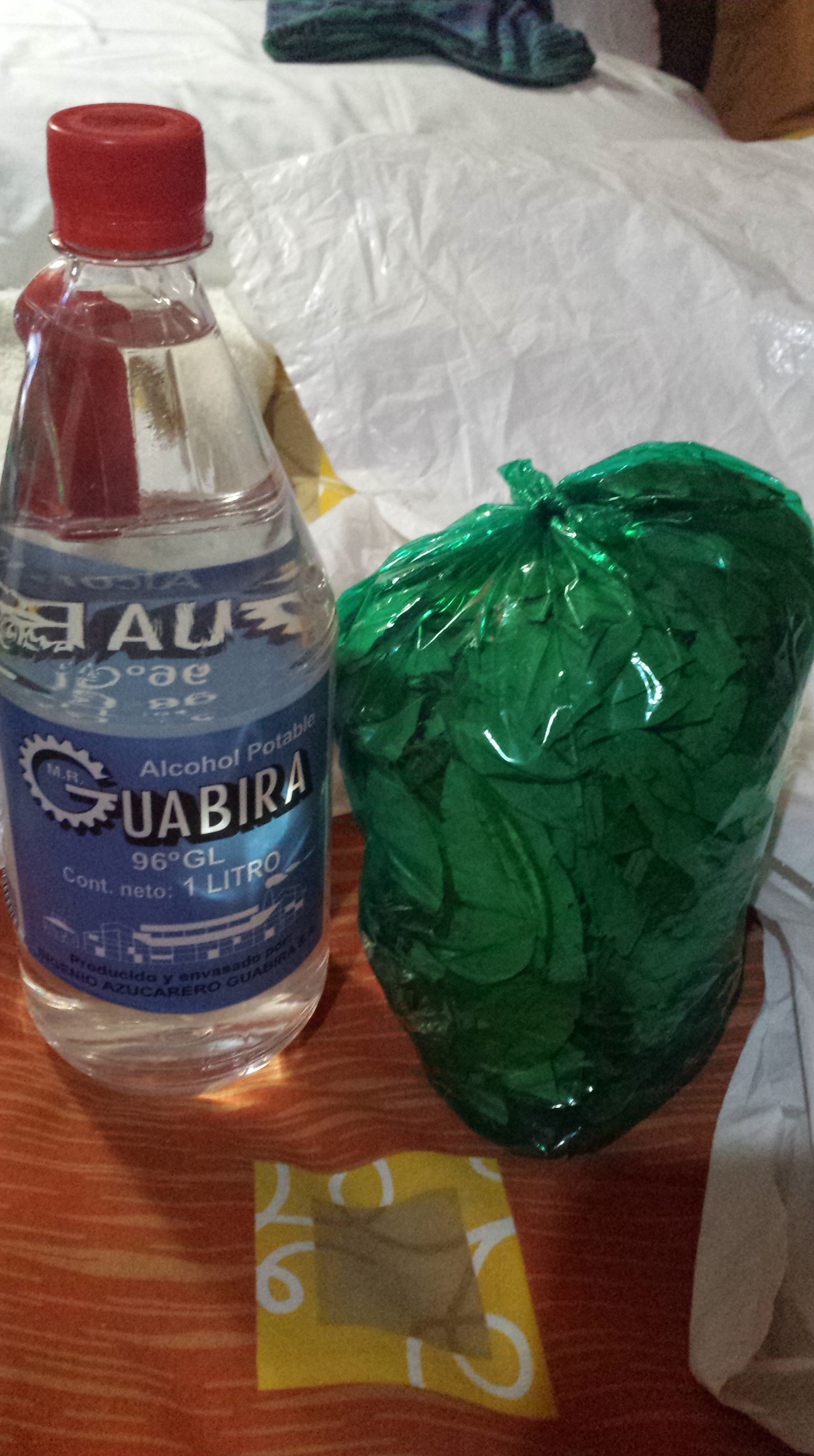

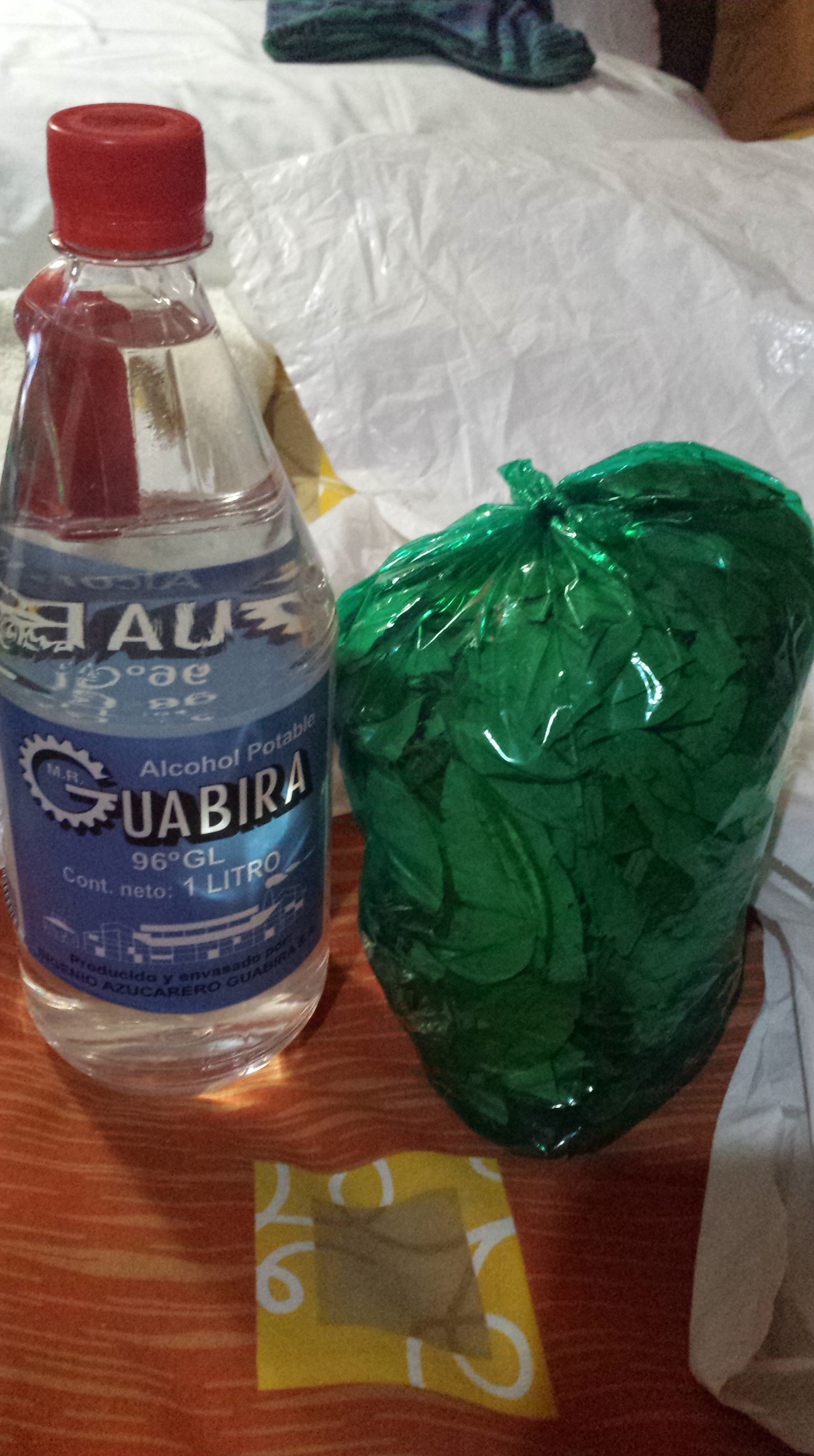

Then there is the business which springs up around having a large group of people all concentrated in one area. Women wheel their carts out and begin selling food and drink. Others wander through the crowd selling sun shades or umbrellas. The favored 96% denatured alcohol is served in tiny plastic cups. Parents buy their children trinket toys.

I regret to inform you, the Fidget Spinner has made it to South America.

Secondary Financial Effects

While at the source the bloqueos and protests are mostly a social affair, the heaviest consequence I witnessed was on the remote mountain villages, those who live at the end of the road. Two weeks after walking out of La Paz, we passed through Uachuani. Of the three shops in town, their shelves were running light on goods, “there has been a bloqueo for 3 weeks in the city [La Paz],” one owner explained as he again proffered a can of grated sardines insisting it was tuna; the only source of protein we could identify.

While what we observed in the city was that the protests only happened during daytime hours, it seems the drivers and food transport individuals did not make runs until they hear it is all over. Piecing together what we had seen in the city, the lack of reliable news to the towns and their reliance on word of mouth, and the pervasive lackadaisical attitude toward production and business, I realized the four day protest we had encountered in La Paz two weeks ago meant these folks did not get food deliveries for weeks after.

Fortunately most families in these areas are largely self sufficient. They raise their own animals, purchase goods in bulk when they go to the city and are equipped to wait out these predictably unpredictable hiccups to production and transport.

Economía de un ‘Bloqueo’

Escrito por Fidgit

Traduccion por Henry Tovar

Al cruzar Bolivia, encontramos solo algunos senderos, algunas carreteras secundarias, una gran cantidad de vías férreas y un tramo largo a lo largo de la Ruta 1 desde Uyuni hasta La Paz, por lo que no se requería mucha navegación. Después de la “fuga de cerebros” que experimentamos en la primera temporada de caminata, mi perspectiva sobre el uso de dispositivos de audio durante la caminata cambió, y mi pequeño dispositivo mp3 se ha convertido en una pieza común del kit. A lo largo de este tramo, mantuve mi mente ocupada y alimentada con podcasts.

Caminando por estas rutas más pobladas, también encontramos ramificaciones de la práctica generalizada de las protestas públicas, a menudo tomando la forma de ‘bloqueos’, en donde los caminos son cerrados por los manifestantes. El primero fue agotador, ya que no estábamos seguros de lo que estaba pasando y habíamos escuchado que estos eventos se volvían violentos. Luego se convirtieron en un evento interesante para observar, luego se volvieron mundanos y algo molesto. Llegamos a llamarlos “protestas los lunes”, aunque eran posibles cualquier día de la semana laboral.

Entonces, cuando el episodio de podcast de Freakonomics “¿Funcionan los boicots?” Llegué a los agujeros de mi oído, me levanté y comencé a observar los bloqueos con más escrutinio. Lo que sigue son algunas observaciones.

Quien está protestando y como?-

Tratamos estas reuniones con precaución, ya que siempre hay una posibilidad, y también una historia, de que estalle la violencia cuando grupos grandes se reúnen para demostrar desagrado. Afortunadamente, cada protesta que enfrentamos fue pacífica, si fue confrontacional; y como un conductor se quejó, en La Paz, “siempre al menos un distrito está cerrado debido a un bloqueo”. Mientras estuvimos allí, las carreteras de nuestro distrito (Distrito Sur) estuvieron cerradas por al menos cuatro días. Todas las tardes en las noticias, hubo informes de que ese día hubo protestas. Un aviso de viaje, de algún tipo.

Curiosamente, parecía ser principalmente mujeres que poblaban las protestas. Salían temprano en la mañana, colgaban pancartas y sogas en las intersecciones, y luego subían en grupos, sentados en círculos conversando y tejiendo en el medio de la carretera, con sombrillas o sombreros que los protegían del sol. Las mujeres aquí parecen estar siempre tejiendo, aunque algo de ganchillo.

Los hombres, si bien eran mucho menos numerosos, generalmente participaban en posiciones activas o de liderazgo. Empujando rocas hacia los caminos, deambulando entre la multitud dando discursos apasionados, parándose en posiciones donde es probable que haya conflicto, o bebiendo a la sombra de edificios alrededor de la periferia.

Por qué / Qué se está protestando

En general, el motivador es financiero, aunque a veces se citan razones sociales. A menudo, es porque les están cobrando dinero que no quieren pagar o no están recibiendo dinero que creen que deberían: un aumento del tres por ciento de la factura eléctrica en Oruro, la liberación de prisioneros en La Paz, un distrito vecino obteniendo más dinero que ellos de la industria del turismo.

Un buen número de individuos, cuando les pregunté de qué protestaban, o se negaron a responder (o incluso a mirarme), no sabían qué se estaba protestando o citaron motivadores diferentes que otros en la misma demostración. Esto ocurrió en las ciudades más grandes. Cuando pregunté a otros bolivianos que no participaron en las protestas, se tuvo la sensación de que muchos de los que se presentaron a estas protestas tienen menores medios, educación y conciencia, y salen a causa de las presiones sociales más que de la información.

Otras veces, se trataba de comunidades más pequeñas reunidas, detenían el tráfico en los puentes y aceptaban dinero para que pasaran los vehículos. Pasamos por uno como este en un pueblo en la carretera a las afueras de La Paz. En el puente nos acercamos, había un hombre del vecindario pavoneándose importante, luciendo muy oficial con un cuaderno escolar rosa anotando no estoy seguro de qué, pero parecía estar aceptando pagos de mini conductores por permiso para pasar. Tres veces le pagaron los conductores y cada vez que aceptó, cuando un grupo de mujeres que estaban de pie al otro lado del puente interrumpió los pagos y le devolvió el dinero.

Finalmente, una camioneta blanca se arrastró por el borde de la ciudad, atravesó el lecho seco del río en medio de la pampa salada y polvorienta y se fue por el otro lado. Tan pronto como todos vieron su nube de polvo, todos los vehículos se desviaron en esa dirección. Autobuses, semirremolques, vehículos de la ciudad brillante, todos tejiendo y chocando. Fue una carrera de rallyes improvisada, con convoys de vehículos no afiliados siguiendo uno al otro, navegando aparentemente al azar.

Impacto Financiero inmediato

Word se propaga rápidamente cuando hay un bloqueo. Así que muchas de las minis, una fuente primaria de transporte público, simplemente no conducen ese día, o manejan diferentes rutas. El chico que todavía está dispuesto a conducir aumenta el precio. Para ser justos, tendrá que encontrar un camino que le permita pasar más tiempo, use su vehículo y consuma combustible (aunque este precio está subsidiado por el gobierno).

Existe el soborno mencionado anteriormente. Sin embargo, uno no debe llamarlo soborno. La mayoría de los que no participaron en la protesta parecen verlo más como un “impuesto de dolor en el culo”. En el bloqueo del poblado mencionado anteriormente, mientras observábamos a los conductores y al hombre en el puente regatear que Neon observaba, “esto es más como una recaudación de fondos del vecindario que nada”.

Luego está el negocio que surge teniendo un gran grupo de personas concentradas en un área. Las mujeres sacan sus carros y comienzan a vender alimentos y bebidas. Otros deambulan entre la multitud que vende sombrillas o sombrillas. El 96% de alcohol desnaturalizado preferido se sirve en vasos de plástico pequeños. Los padres les compran juguetes a sus hijos.

Lamento informarle que Fidget Spinner ha llegado a Sudamérica.

Efectos financieros secundarios

Mientras que en la fuente los bloqueos y las protestas son en su mayoría un asunto social, la consecuencia más grave que presencié fue en los pueblos remotos de las montañas, los que viven al final del camino. Dos semanas después de salir de La Paz, pasamos por Uachuani. De las tres tiendas en la ciudad, sus estantes se iluminaban con productos, “ha habido un bloqueo durante 3 semanas en la ciudad [La Paz]”, explicó un propietario mientras ofrecía una lata de sardinas ralladas insistiendo en que era atún; la única fuente de proteína que podríamos identificar.

Mientras que lo que observamos en la ciudad fue que las protestas solo ocurrieron durante el día, parece que los conductores y las personas que transportan alimentos no corrieron hasta que escucharon que todo había terminado. Remontándonos a lo que habíamos visto en la ciudad, la falta de noticias confiables para los pueblos y su confianza en el boca a boca, y la actitud dominante e indiferente hacia la producción y los negocios, me di cuenta de la protesta de cuatro días que tuvimos en La Paz dos semanas atrás significaba que estas personas no recibían entregas de alimentos durante semanas después.

Afortunadamente, la mayoría de las familias en estas áreas son en gran medida autosuficientes. Crían sus propios animales, compran productos a granel cuando van a la ciudad y están preparados para esperar a que estos imprevisibles y previsibles hileras de producción y transporte.