Haz clic aquí para leer en español

Written by Fidgit

“Se han acostumbrados,” she shrugged.

This was the summation a kiosk owner in Huallanca offered on why the communities along the Huayhuash Circuit expected payment from passing hikers.

We were standing at the T-intersection on the edge of town, just beside her kiosk where a kitten and a small dog played in the sun. She had seen us casting about uncertainly for a vehicle and had come out to offer advice and support on hitching back out to our route. She was cheery, friendly, and curious. We bought a few trail snacks from her shop. This practice of reciprocity is important in our endeavor.

“When tourists first came to the Huayhuash,” she explained, “they would ask local people to guide them and then give them money. Sometimes they just gave people money, so the people got used to that,” she shrugged.

It sounded like good intentions set a precedent which, with time and increased use, had become the money grubbing loop hike we had hurriedly left behind. It recalled me to the now packed long distance trails in the US and to feel fortunate to be on the front end of the still relatively small wave of people walking across South America.

Huallanca is along the northern edge of the Huayhuash range and is surrounded by mines. Same with the town to the south of the Range. Same with the towns to the east. The famous adventure travel hiking circuit is surrounded by mines but most visitors will have no idea of this because they hire guide companies, hike the loop, check it off their ‘bucket list’, snap the pictures to get the ‘likes’, and leave by the same transports as they came in.

We had walked up the eastern side of the staggeringly beautiful loop. While the mountains most definitely merit the fame, the development of the industry around it was haphazard and unmanaged. Trails were deeply trenched and, when we passed early in the season, were literally running with water. Dozens of ad-hoc foot paths had been worn by visitors trying to keep their ankle high waterproof boots dry, and the guides, wanting their guests to have the best time possible, simply allowed it. Erosion was already hard at work on the steep passes.

What most bothered me were the communities in each valley along the way, roughly every 10 km or so, sent people up to extol payment from passing tourists ranging from $7-$21 USD per person, even just for passing.

I want to be open that my response to this is layered with frustrations:

1) I resent being charged money to be in wilderness in almost any case.

2) Recent months spent crossing two countries of people almost constantly asking us for “propinas,” (tips) or “dulces” for doing nothing more than passing one another on the street.

3) A very specific frustration with being charged money at places such as Rainbow Mountain and a few other new and unregulated “wilderness attractions” to fund practices which I do not see to be in the long term interest of the land or the people.

I am Jill’s self-righteous indignation.

Essentially, the villagers saw or heard from another community the opportunity to acquire an income, they set their own prices and develop the areas as they see fit.

At Rainbow Mountain, this meant a pit toilet about every 100 m in climb along the way, a constant carousel of horses being led by locals clad in brightly colored outfits, unsecured trash cans releasing garbage into the wind, and some sort of sketchy structure being built over the stream (I’m guessing it will be a restaurant?).

Along the Huayhuash, it seemed generally to be maintaining a camp ground surrounded by trash, toilets surrounded by TP flowers and turds, and selling beer in glass bottles and carbonated beverages and water in plastic bottles.

Where we entered the loop, at the hot springs on the southern end, we paid 20 soles each to pitch our tent and use the hot springs, which they manned and cleaned. Never mind the locals taking soap baths in one of the pools and encouraging the tour groups to wash their clothes also with soap, which then ran into the stream which then flowed into their village downstream . . .

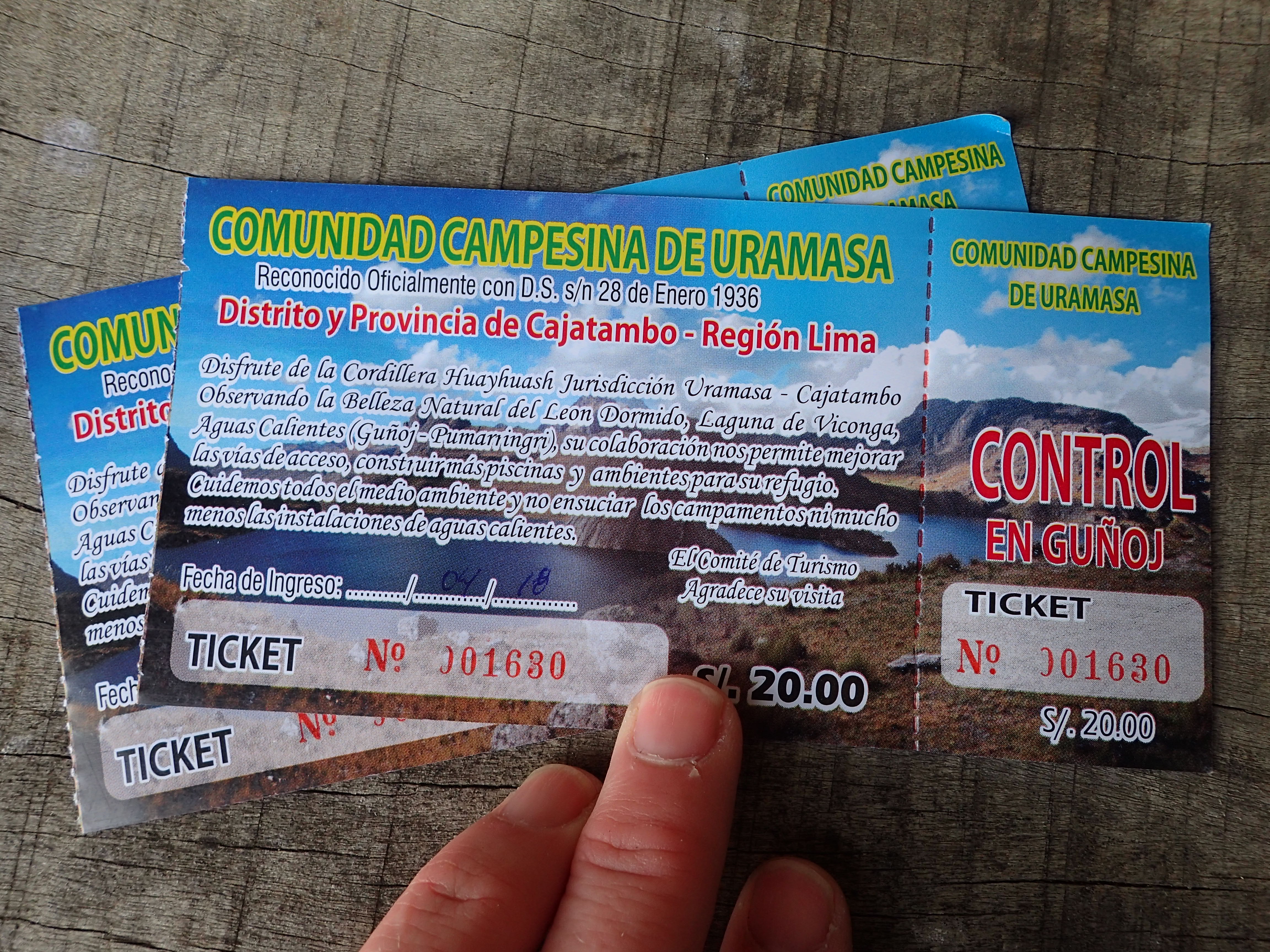

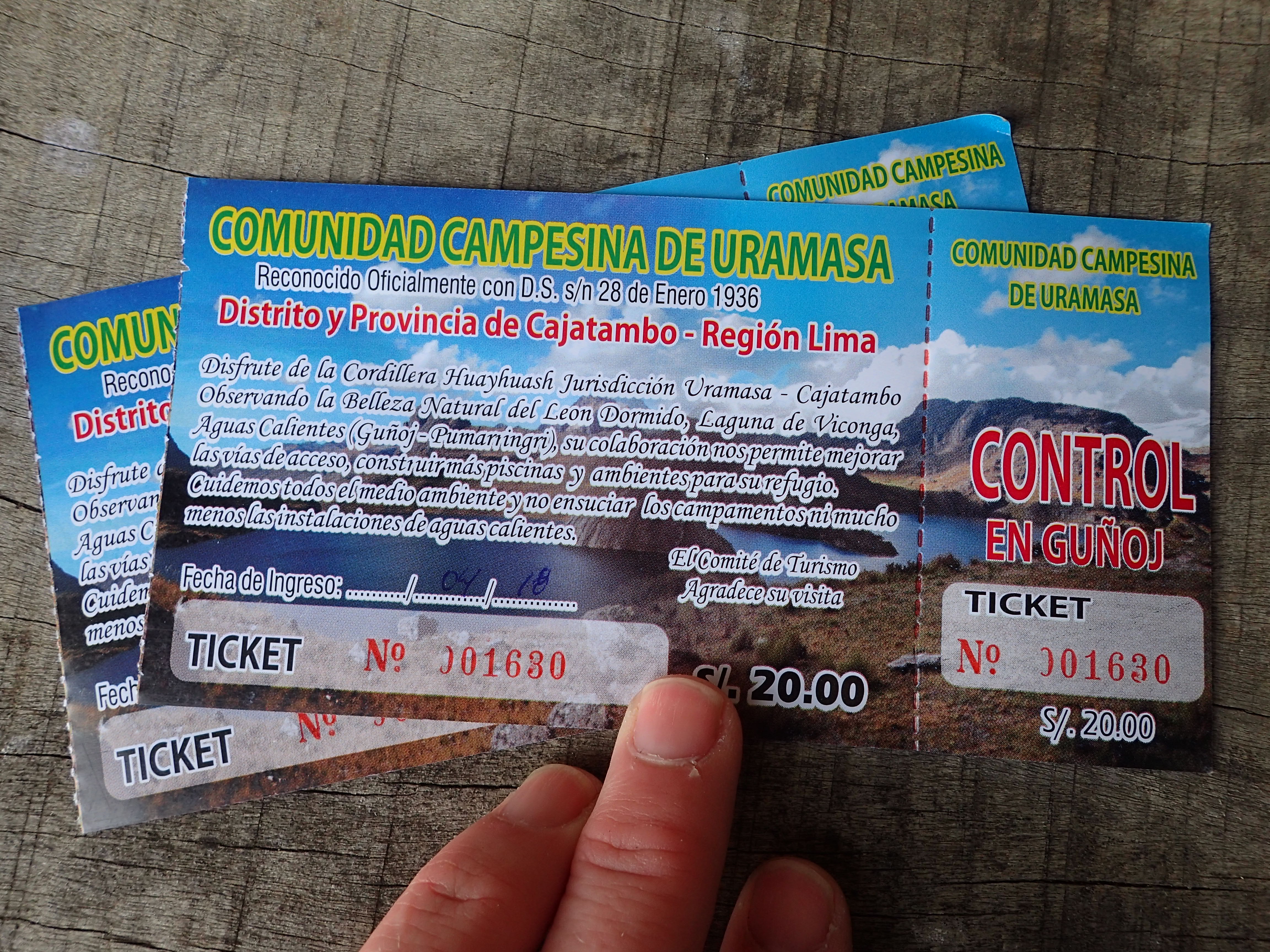

My ire peaked the next day when we attempted to walk past another of these sites and were blocked from passing by a man demanding another 20 soles per person. We showed him our colorful little tickets and he said these were for a different community. We explained that we would be hiking on to the next valley and not camping there. He said we still had to pay.

“Why are you being difficult about this, all the other tourists just pay and don’t say anything,” he insisted.

Here I felt we came close to the root of the issue I meant to confront. Mindless acquiescence to ordinances applied by people who, while coming from a deep history of the land, have no concept of land management and do not yet grasp the literal and figurative garbage the expectations and products of the first-world are raining down on them. Chemicals, over use, poor maintenance, etc.

Of the potentially responsible parties: i.e. – the enterprising locals or the visiting tourists, I feel the responsibility for prompting progress falls in the lap of the tourist. Yet, what I saw in general was vacationer’s laziness, unquestioning, self satisfying, path of least resistance:

“The guide said it was okay to wash my clothes in the stream,”

“I don’t want to get my boots muddy,”

“Someone will come pick up my trash,”

“It is just money and these poor wretches need it more than me,”

all the drivel of the privileged.

We are the ones with the benefit of education and perspective on what happens when resources are strained, we’ve already wrought these consequences on our own lands. How dare we come dump our trash on theirs while they, in good faith, trust us and hope we are bringing them economic solvency which they still, also because of us, believe is the only way up.

So, I again asked what we were being charged for. He replied, for using the land and for our protection. I told him we carried our own protection and would not be using the land. I pressed him about how the money was used. For example, if there were some organization or project afoot teaching health, rescue, LNT, and trail work to the communities, I would be thrilled to pitch in.

He replied it was “for the community” but could not clarify beyond that. The understanding I have pieced together is the money is taken back to the community, dolled out by their leaders variously for land projects and among the residents.

“If you can’t pay, then you’ll just have to stay the night here and pay in the morning,” he declared.

“Sir, as I don’t have money now, unless there is an ATM up here, I am still not going to have money in the morning.”

He gave this some thought.

I explained we had not anticipated these constant expenses and did not to travel with much cash as that was a good way to get robbed. I did not have the amount of money he was asking as we had paid almost all we had at the hot springs camp the evening before. I offered him the 3 soles I had and a bar of soap and a small shampoo I carry to give to folks we meet along the way.

He snorted, “I can’t bring that back to my community, what am I going to do with soap and shampoo?”

“Maybe you can come together as a community, vote on who smells the worst, and give it to them?” I suggested.

He looked at me like I was batty, “No, the community only want your money.”

I felt like he heard himself say it at the same time as I did.

As a region with deep roots in collective thinking and a relatively recent place of refuge for the Communist offshoot, the Sendero Luminoso, obsession with wealth is frowned upon. This prompted a shift in the conversation.

Next he offered to half the price, then he told me I had to give him whatever I had, whereupon I again offered him the 3 soles and the wash products, he surmised, “if that is really all you’ve got, and you’ll have to answer to God if you are lying, then just don’t worry about it and move on. But if we find you camping here, you will have to pay.”

We hiked on, edgy but relieved. We went through almost the same situation in two more valleys but with less resistance, giving out the soap and shampoo and a few of my snacks in trade for “safe passage”, made sure to stealth camp high and remote, and got off the Huayhuash Circuit as quickly as possible.

This experience gave rise to my summation of Peruvian people:

If you have nothing, they will try to help.

If you have something, they want a piece of it.

As a nod to your having plowed through my belly aching and opinion spewing, here is a clip from one of the most beautiful days along that section of hiking.

[youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nM0znFVC_2c&w=560&h=315]

La frustración con el circuito de Huayhuash y el precio de los viajes complacientes

Traduccion por Henry Tovar

Escrito por Fidgit

“Se han acostumbrados,” she shrugged.

Esta fue la suma que un propietario de un kiosco en Huallanca ofreció sobre por qué las comunidades a lo largo del circuito de Huayhuash esperaban el pago de los excursionistas que pasaban.

Estábamos parados en la intersección en T en el borde de la ciudad, justo al lado de su quiosco donde un gatito y un perro pequeño jugaban al sol. Nos había visto echando con incertidumbre un vehículo y había salido a ofrecer asesoramiento y apoyo para volver a nuestra ruta. Ella era alegre, amigable y curiosa. Compramos algunos snacks de su tienda. Esta práctica de reciprocidad es importante en nuestro esfuerzo.

“Cuando los turistas llegaron por primera vez a Huayhuash”, explicó, “pedían a la gente local que los guiara y luego les daba dinero. A veces simplemente le daban dinero a la gente, para que la gente se acostumbrara a eso”, se encogió de hombros.

Parecía que las buenas intenciones sentaban un precedente que, con el paso del tiempo y el uso creciente, se había convertido en el aumento de dinero que habíamos dejado atrás. Me recordó los senderos de larga distancia ahora llenos en los EE. UU. Y me siento afortunado de estar al frente de la ola relativamente pequeña de personas que cruzan Sudamérica.

Huallanca se encuentra a lo largo del borde norte de la cordillera de Huayhuash y está rodeada de minas. Lo mismo con la ciudad al sur de la Cordillera. Lo mismo con las ciudades del este. El famoso circuito de excursiones de aventura está rodeado de minas, pero la mayoría de los visitantes no tendrán idea de esto porque contratan compañías de guías, recorren el ciclo, lo comprueban en su “lista de deseos”, toman las imágenes para obtener los “Me gusta” y se van por los mismos transportes que entraron.

Habíamos caminado por el lado este de la curva asombrosamente hermosa. Si bien las montañas definitivamente merecen la fama, el desarrollo de la industria a su alrededor fue desordenado y sin control. Los senderos estaban profundamente trincados y, cuando pasamos a principios de la temporada, literalmente corrimos con agua. Decenas de senderos ad-hoc fueron usados por visitantes que trataban de mantener sus botas de tobillo de alta resistencia al agua secas, y las guías, queriendo que sus invitados tuvieran el mejor tiempo posible, simplemente lo permitieron. Erosión ya estaba trabajando duro en los pasos empinados.

Lo que más me molestó fueron las comunidades en cada valle a lo largo del camino, aproximadamente cada 10 km más o menos, enviaron personas para exaltar el pago de los turistas que iban de $ 7- $ 21 USD por persona, incluso solo por el pase.

Quiero ser abierta, mi respuesta a esto está plagada de frustraciones:

1) Me molesta que se me cobre dinero por estar en el desierto en casi cualquier caso.

2) Los últimos meses pasaron cruzando dos países de personas casi constantemente solicitandonos propinas, propinas o dulces por no hacer nada más que pasarse en la calle.

3) Una frustración muy específica al cobrar dinero en lugares como Rainbow Mountain y algunas otras “atracciones silvestres” nuevas y no reguladas para financiar prácticas que no creo que sean de interés a largo plazo para la tierra o las personas.

Soy la indignación de Jill por su propia justicia.

Esencialmente, los aldeanos vieron o escucharon de otra comunidad la oportunidad de obtener un ingreso, establecieron sus propios precios y desarrollaron las áreas como mejor les pareciera.

En Rainbow Mountain, esto significaba un inodoro de pozo cada 100 m en ascenso en el camino, un carrusel constante de caballos liderados por lugareños vestidos con atuendos de colores brillantes, botes de basura desprotegidos que arrojaban basura al viento y una especie de estructura superficial construido sobre la corriente (supongo que será un restaurante?).

A lo largo del Huayhuash, en general parecía mantener un campamento rodeado de basura, inodoros rodeados de flores y turrones, y vendiendo cerveza en botellas de vidrio y bebidas carbonatadas y agua en botellas de plástico.

Donde entramos al circuito, en las aguas termales en el extremo sur, pagamos 20 soles cada uno para armar nuestra tienda de campaña y usar las aguas termales, que atendieron y limpiaron. No importa que los lugareños tomen baños de jabón en una de las piscinas y alientan a los grupos a lavar la ropa también con jabón, que luego se encontró con la corriente que luego fluyó a su pueblo río abajo…

Mi ira alcanzó su punto máximo al día siguiente cuando intentamos pasar por otro de estos sitios y se nos impidió pasar por un hombre que pedía otros 20 soles por persona. Le mostramos nuestras coloridas entradas y dijo que eran para una comunidad diferente. Explicamos que iríamos de excursión al siguiente valle y no acampar allí. Dijo que todavía teníamos que pagar.

“¿Por qué estás siendo difícil con esto, todos los demás turistas solo pagan y no dicen nada?” insistio.

Aquí sentí que nos acercamos a la raíz del problema que quería enfrentar. Consentimiento ciego a las ordenanzas aplicadas por personas que, aunque provienen de una historia profunda de la tierra, no tienen ningún concepto de manejo de la tierra y aún no captan la basura literal y figurativa que las expectativas y los productos del primer mundo están lloviendo sobre ellos. Productos químicos, uso excesivo, mantenimiento deficiente, etc.

De las partes potencialmente responsables: es decir, los lugareños emprendedores o los turistas visitantes, siento que la responsabilidad de impulsar el progreso recae en el regazo del turista. Sin embargo, lo que vi en general fue la pereza del veraneante, incuestionable, autosatisfactorio, el camino de menor resistencia:

“La guía dijo que estaba bien lavar mi ropa en el arroyo”.

“No quiero ensuciar mis botas”

“Alguien vendrá a recoger mi basura”

“Es solo dinero y estos pobres desgraciados lo necesitan más que yo”.

todos los tontos de los privilegiados.

Ensuciarse y superarlo.

Nosotros somos los que tenemos el beneficio de la educación y la perspectiva de lo que sucede cuando los recursos se agotan, ya hemos forjado estas consecuencias en nuestras propias tierras. ¿Cómo nos atrevemos a tirar nuestra basura en la de ellos mientras ellos, de buena fe, confían en nosotros y esperamos que les brindemos solvencia económica que ellos todavía, también por nosotros, creen que es el único camino hacia arriba?

Entonces, nuevamente pregunté por qué nos estaban cobrando. Él respondió, por usar la tierra y por nuestra protección. Le dije que teníamos nuestra propia protección y que no usamos la tierra. Lo presioné sobre cómo se usó el dinero. Por ejemplo,

Si hubiera alguna organización o proyecto en curso que enseñara salud, rescate, LNT y trabajo de senderos a las comunidades, estaría encantado de contribuir.

Él respondió que era “para la comunidad” pero no pudo aclarar más allá de eso.

El entendimiento que he reconstruido es que el dinero se transfiere a la comunidad, distribuido por sus líderes de diversas maneras para proyectos de tierras y entre los residentes.

“Si no puedes pagar, entonces tendrás que pasar la noche aquí y pagar por la mañana”, declaró.

“Señor, como no tengo dinero ahora, a menos que haya un cajero automático aquí, todavía no tendré dinero por la mañana”.

Él pensó un poco.

Le expliqué que no habíamos previsto estos gastos constantes y que no habíamos viajado con mucho dinero ya que era una buena forma de robar. No tenía la cantidad de dinero que estaba pidiendo, ya que habíamos pagado casi todo lo que teníamos en el campamento de aguas termales la noche anterior. Le ofrecí los 3 soles que tenía y una barra de jabón y un pequeño champú que llevo para regalar a las personas que encontramos en el camino.

Él bufó, “No puedo devolver eso a mi comunidad, ¿qué voy a hacer con jabón y champú?”

“Tal vez puedas unirte como comunidad, votar por quién huele peor y dárselos”. Sugerí.

Él me miró como si estuviera extravagante,

“No, la comunidad solo quiere tu dinero”.

Sentí que se había escuchado decirlo al mismo tiempo que yo.

Como una región con profundas raíces en el pensamiento colectivo y un lugar de refugio relativamente reciente para el vástago comunista, Sendero Luminoso, la obsesión por la riqueza está mal vista. Esto provocó un cambio en la conversación.

Luego ofreció la mitad del precio, luego me dijo que tenía que darle todo lo que tenía, luego le ofrecí nuevamente los 3 soles y los productos de lavado, supuso, “si eso es todo lo que tienes, y tú Tendrás que responderle a Dios si estás mintiendo, entonces no te preocupes y sigue adelante. Pero si te encontramos acampando aquí, tendrás que pagar “.

Fuimos de excursión, nervioso pero aliviado. Pasamos casi por la misma situación en otros dos valles, pero con menos resistencia, repartiendo jabón y champú y algunos de mis bocadillos en el comercio para un “paso seguro”, me aseguré de ir sigilosamente al campamento y me alejé del Huayhuash Circuito lo más rápido posible.

Esta experiencia dio lugar a mi resumen de los peruanos:

Si no tienes nada, tratarán de ayudar.

Si tienes algo, quieren un pedazo de él.

Como un guiño a que me hayas atravesado el estómago dolorido y la opinión que vomitas, aquí hay un video de uno de los días más hermosos de esa sección de la caminata.

[youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nM0znFVC_2c&w=560&h=315]

Comments (4)

I so appreciate your observations and insights. Exploitation comes in many forms and arises for a variety of reasons. Good job drilling down to the bottom line.

Interesting account and gorgeous pictures!

Out of curiosity, what kind of protection did you have? Also, if you hire a guide are you still expected to pay with every new village?

I carry pepper spray but more important I think is awareness of warning instincts and knowing how to read indicators which help you avoid difficult situations altogether.

From the guided folks I spoke with, yes, they were each expected to pay full price for each territory they passed as well.

Interesting. Thanks for answering! Happy travels!