*Written by Fidgit*

Three scene and character sketches from our ride of the Baja Divide.

Expendio Café Batalla

We happened upon this local little coffee grinder shop we adore in La Paz. Neither of us knows when exactly coffee became an almost mandatory part of our morning routines, somewhere around Peru or Ecuador, likely, where the coffee started to get good. But maybe making the instant coffee in Patagonia trained us. Either way.

The shop is down from the plaza, near the church where Queen Elizabeth II once walked from the dock. The two outward facing walls are primarily window with bars across them. The door enters from the corner into an open, empty floor facing two walls lined with wood paneled counters. The counter in the corner is a self serve affair. Styrofoam cups, cream and sugar in corrugated glass containers with metal lids. Based on the small can on the countertop being filled with trash, it appeared most people use the packets of Stevia and powdered creamer instead.

Old bucket bus station seats line the two walls which flank the door. There are always locals occupying them, sipping coffee. The sound of the grinders echoed through the open space. The first time we stumbled upon Cafe Batalla, the seats were full. We walked in to a chorus of buenos días.

buenos días, we replied, looking at each person in turn. it is like saying buen provecho when you see someone eating. Or despidiendote from each person individually before you leave a social gathering. They call it being educado.

I though about it for the first time the other day. Educado directly translates as “educated” but when we say it in Latin America it means “polite”. A person who knows how to conduct themselves with manners. These two things, education and courtesy, are pretty closely associated. Some consider it antiquated and you won’t see it everywhere but amongst the elders in particular, it quietly matters. For us, as white people you get a pass, or perhaps more of a dismissal, for not being educado. It’s fine, really. It also just seems to please them when you do know the rules. It makes me proud to have grown up in this culture and know to notice some of these things. And to have explained them to Neon and that even she, US raised and a practical, efficiency oriented, and linear thinker, now also recognizes and practices. Plus, there is just something affirming about walking into a room of people and everyone acknowledges you.

There were two homeless gentlemen against one wall and a number of well kempt individuals sitting against the other. Conversations were going, arms were being gripped for emphasis, expressive gestures. One of the homeless guys in a Dodgers cap struck up a conversation with us in English. he spoke it fluently and did so at a high volume. The entire shop quieted down and listened as he spoke to us, with only the whir of the grinders going. The ability to speak English is a skill much admired amongst most in Latin America, and by his doing so, he was showing everyone in the shop his skill and value. A sort of, “subvert the social order”, act. He enthusiastically told us about his days in the US. How he was a teacher and his love of baseball. “I was there legally,” he announced, unprompted.

Two coffee grinders are built into the long counter and the same woman is always working them. She has 3 different kinds of beans, which she encourages you to nibble before making a selection. The machines seem to constantly be whirring. Amidst our team we joke there is a mandatory sound ordnance, in that, there must always be some sort of noise. Whether it is a generator, barking dog, speaker strapped to a truck announcing the fruit or refurbished toasters he is selling, there must be some sort of sound blanketing every populated corner and crease of the country. In the cities it reaches a crescendo. Sometimes intolerable to us when other factors are stressing us out but observing their behavior, it seems almost to be a comfort thing. An interesting difference in perspective to note.

Sr David de Guillermo Prieto

The day was getting hot and there was no shade. Just cactus. An ejido so small it hadn’t been marked on our Baja Divide Route, unnamed on most of our map sources, but there were a couple streets and it was about lunch time. We lapped the front edge of the town, considering stopping in the shade of the brick wall of an abandoned building but the sun was at his peak and shade was more an idea than a reality. We were all hot and tired from a morning of sand and exposure.

My reasoning and temper were short circuiting as we over-discussed the few options we saw. I recognized the hallmark of being miserable and that we were making choices to stay miserable so decided to see if I could change that. We rode back a couple blocks to where a young man was washing a blue tractor which he kept running (probably in order to comply with the mandatory noise ordnance). He seemed surprised to see us and even more that I spoke Spanish. I asked if there were refrescos to be had and he pointed us up the street and around the corner, to the white house. I thanked him and we made short work of identifying the large shady awning near a plywood closet built onto the front of a house. It was the red cooler out front that gave it away.

Sr David had been watering the plants in his yard and working on a machine in the side yard but he crossed the road to attend us. The shop was technically his brother’s but he was in the city so Sr David helped. La Jefa had tasked him with working on the laundry machine which was acting up and he had to move the hose to the different trees but he sat with us for most of our lunch break.

He spoke of being raised in el Arco, a now faltering mining town which reminded me of South Pass City along the Continental Divide in the Basin. He had been working since he was 15. For 40 years he had worked, and he was very proud of that. Now he was retired and this was his country home. His brother had the house across the street, his sister had the house just to the west of his. His other brother was down the block. He told us of family gatherings and showed us videos of his nephew who is in a band and lives in San Diego. He had seen the guitar in Birdie’s backpack and, like so many of the Mexican campesinos immediately connected to the music. A month before a rancher had come out to his fence and stood singing norteño ballads we passed through his gates.

Sr David had been watching cyclists pass through here for a couple years now, he recons. A steady flow of us for the past 2 years. Like the owner at the ranch 30 km before he wondered why the cyclists kept going the hard way, straight into where the sand was the most pesado?

Paraphrasing him now, “I see people ride up from the worst road and they stop on the edge of town, right there. They never come in to saludar. They just look at their phones and then go that way, into even more sand!” He seemed honestly perplexed by the whole affair. Why would they go the hard way? Why wouldn’t they ask for directions? Why wouldn’t they come say hi?!

I explained we all had a route descargado to our phones and many of us just followed that. Also, many of us don’t speak Spanish and we are intimidated by trying to communicate. I then inquired about the route it marked ahead, going straight down a tiny dirt road.

“About half the people go that way and the other half just ride the 12 km out to the highway and into the town. That is the way we go. Yesterday I saw un hombre mayor riding alone and he went that way.”

People who have spent their entire lives at hard manual labor seem fascinated by the relatively large number of older white people riding the Baja Divide. What kind of life did these people lead that they want more physical hardship in their twilight? I wonder if there isn’t some sort of lifestyle reversal between the cultures?

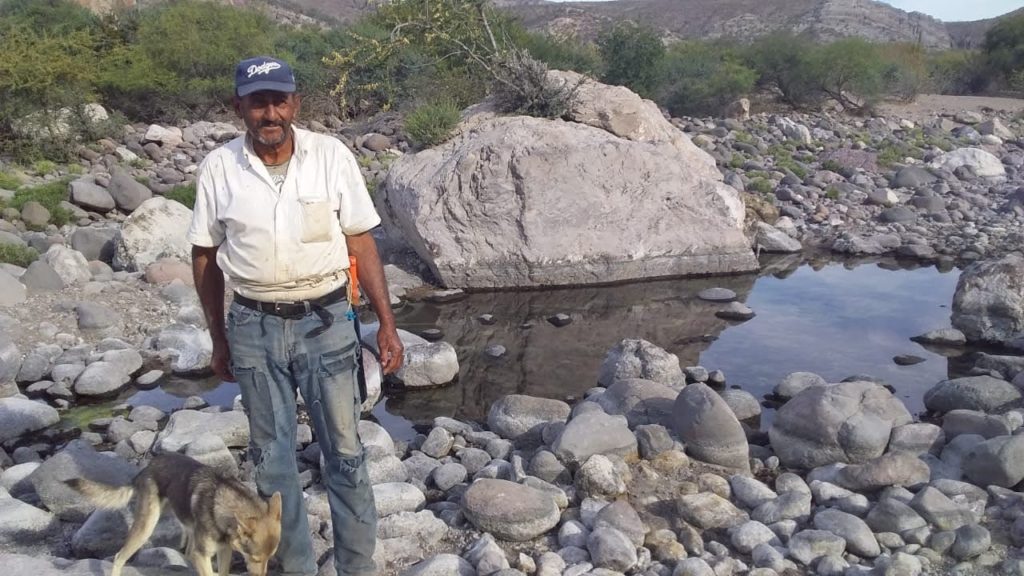

The Goat Herder- Almonte

It had been a glorious and winding descent of almost 2,000 ft into the sunset. You know a dirt back road in Mexico is steep when they pave chunks with concrete slabs! Either way, we flew, veering around the human size potholes and avoiding the sheer cliff edges as the landscape melted through the colors of evening. We arrived to the valley floor and a river bed just as the herders were putting the goats into their pens. Filling our water bottles from the clear pools still standing after a wet winter, Birdie and I waited for Neon After 20 minutes and as darkness overtook the skies, I began to worry and we backtracked a bit and while Birdie made camp I began to climb back up the mountain. Lucky for me, only one rise later I met her coming down, she had dropped her music player along the way and had to hoof it back up to collect it.

We camped just off the road and the local dog population howled about it and in the morning, came to investigate and bark at us while we broke camp, until deciding we were okay and hanging out, then inquiring whether we had any food. We let them lick the remains of our tuna cans, a common protein source and lunch fare for us. A truck stopped by and asked Neon about the route. They were locals who had seen cyclists coming through their town regularly but did not know why. They were excited about the potential income prospect we cyclists presented and we encouraged them.

We again crossed the riverbed, again stopping to collect more water for the day’s ride. The herders were just beginning to move their goats out of the pen and driving them toward the mountains for a day of gazing, blowing fart noises with their mouths, jumping on things, and whatever else goats do. Almonte stopped in his task and ambled over to say hello. Greetings and introductions completed, he stood looking over us and our gear.

He asked if we had any medicine for his dolores. Whether it was the miners in Bolivia or the fishermen in Panama, this has been a common request we get along the journey. I find it a great chance to give a small gift and so always carry a large bottle of Ibuprofen from which to share. I will give them about 10 or 12 pills, with specific and clear directions on dosing and to only take the medicine after a meal. He nodded solemnly and thanked me. He pulled a small handkerchief out of his breast pocket and carefully wrapped and stored them.

He said he had seen us the night before but by the time he was done with his animals and came to invite us in for a coffee, we had disappeared.

“When will you be by again?” he asked.

I said I wasn’t sure yet.

“Next year?” He insisted.

“Perhaps,” I replied.

“I live on the hill right there, so now you know for next time you come through.” He pointed and concluded.

We capped our bottles and took turns saying goodbye and shaking hands. By now his 100 head of goats had flooded past and he followed them into the ocatillo. Soon a horseback gentleman pulled the reign on his pony and stood watching us until we greeted him and started the whole exchange over again.

Photo Credit: Brian ‘Birdie’ Tripp

We are able to be on this journey because of our contributors, supporters, and incredible partners, like Forever Cairn. Support a local, earth conscious, woman owned business.