February 2022

“Febrero loco, Marzo otro poco.”

– Mexican Saying

Diversity abounds throughout Mexico and Central America. Language, culture, weather, climate, food, and vegetation all change from one valley to the next. There are also overarching patterns, such as: tortillas with every meal, unpredictable weather of February and into March, then the April heat wave.

Another predictable pattern are the specific points where foreign visitors flock and, thus, infrastructure and expectations rise to meet the inflow. Oaxaca is one such region and I must say, for all the well known points of interest, there are 10 fold more hidden. With over 700 endemic plants, 100 bird species, spices and flavors for every palette, 16 individual ethnic groups, fabrics and patterns to reflect the women and communities who weave them, all at a global crossing point for still thousands more guests passing through. How much you can explore and learn is limited only by time and curiosity!

I will here share a few tidbits we learned about the history and interplay of characters such as mezcal, art, maize, ancient cultures, ahuehuete trees, and the Mitla site but moving in to it you must know, this doesn’t even begin to scrape the surface of what this state brings to bear.

Entering the state of Oaxaca, we immediately noticed the surge in agave fields. Rows spanning as far as they eye could see, in every direction, rotating crops, of increasing size. When I asked these men if I could take a picture, they called out, “claro!“, but insisted I take it from a few rows over, where the plants were slightly bigger.

It was such a simple example of the connection with and pride in the land and labor these folks feel. Still, I couldn’t help but wonder at the plump, verdant spines against the arid landscape, just how these thirsty beings could fare at such a high volume. This is wrapped up in politics. “Production was initially limited to six states, but has since expanded to include communities in 11 different Mexican states, although more than 70 percent of mezcal is made in Oaxaca.” Source

In some nooks of the state, folded into the hillsides, were massive agave, with arms spanning wider than our bikes and standing taller than myself. Next to them, a field razed, with the limbs strewn about. They looked like battle fields. Pedaling into the town, we would see a truck, full of the trimmed hearts, with humans chatting happily around their haul, which would eventually be smoked and milled to make the drink.

I’d been reflecting on the nature of sacrifice since Malinalco, since I began to feel the price my body pays for what we are doing, and this added a new component. Realizing that to produce this liquor meant the cultivation, dismemberment, and cutting the very heart out of the agave. The same thing the ancient cultures had done with humans. On top of that were the acrid plumes of brown smoke which dotted the skyline of each subsequent wide valley. Filling our lungs as we climbed, blanketing their homeland, hanging low over what few bodies of water we did see. I felt deep doubts upon seeing a drooping little burro standing in full sun on cement, strapped to its mill on the side of the road, hoping to attract a tourist bus to stop.

I do not share this to disparage the tradition, only to impress upon those who might be so fortunate as to enjoy it, to better appreciate all which goes into it. It was an honor to taste on my tongue even as the smoke filled valleys were a tax on our lungs. Every gift comes at a cost and the cost structure of this particular art form, may not be sustainable. I won’t pretend to speak to the extent of it but this article helps unravel some of the juxtapositions which wrestle inside my chest.

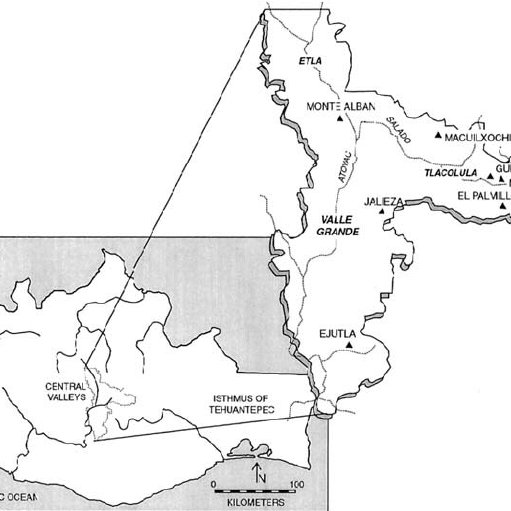

The city of Oaxaca itself, sits at the confluence of 3 valleys: Etla, Valley Grande, and Tlacolula (image source). Coinciding with 3 ranges: the Nudo Mixteco, la Sierra Juárez, y la Sierra Madre del Sur. It has also been a meeting point between peoples of shifting power and thus, a point of both power and conflict.

Descending into the city from the northern Etla valley, zipping through alfalfa fields and around burro drawn carts loaded high, stopping for street quesadillas from an abuela and her tiny nieta who assured us brains was her finest available delicacy, we took our treats to enjoy at the San Jose de Mogote Ruins.

Since it was untended, I went to chat with a fellow who lived at the bottom of the stairs to ask if we could leave our bikes while exploring the site. He commented that he had been waiting to see if I would greet him, that most gringos just ignore him and he seemed chuffed that I spoke Spanish. Then he said one of my favorite things to hear, that yes our bikes were safe, “todo es muy tranquilo aquí.” Things are not ‘safe’ or ‘dangerous’ they are either tranquilo or complicado.

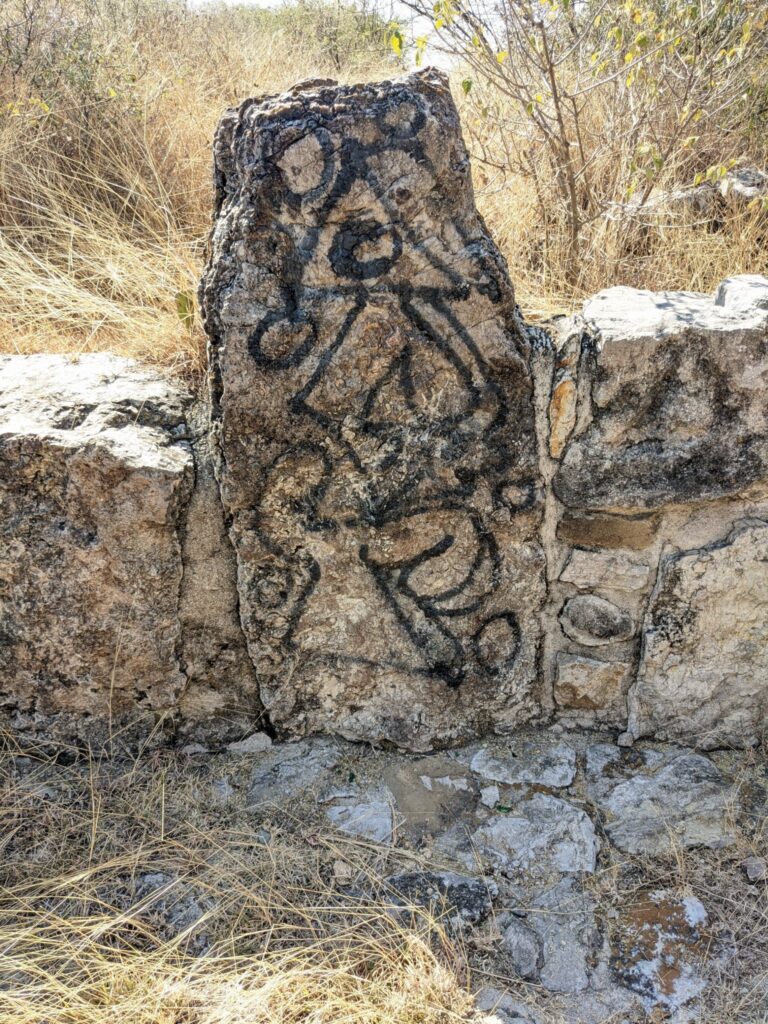

People complain about how some of these sites aren’t “protected.” Conferring with the cactus who stood lookout up top, sharing bits of lunch with the perros callejeros below, watching the bees and wasps work diligently, I’d say it has plenty of guardians. Now if only humans could get on pace and learn to coexist without destroying. Even the termites at work within certain dead limbs of the guardian Blue Myrtle Cactus were playing a part.

To this, graffiti is part of the story. If we don’t like it, it’s because we don’t like what it says about us. If this is what we have to add, then, so it is. These rocks talk. They escort us through time, tablets for the telling. We are tomorrow’s history.

Only later, when we hired a guide to tour Monte Alban did we learn that site, where we meandered and munched lunch to gather ourselves and our intentions before delving into the city, was in fact the seat of regional power long before Monte Alban even rose. The forgotten, grafittied, stonework was what remained of the first capital of the Mixtec peoples. I’ve already written about the Monte Alban Ruins, a pre-eminent stop for visitors and a site so important it adorns the 20 peso note.

One of our safety practices is to read the messaging around us. What does the garbage in the ditches tell us: hypodermic needles, diapers, liquor bottles, etc. How do people’s body language read, where do eyes lead, do they greet you back? What do the walls say?

On the outskirts of the city, just past the tourist circuits, were the hastily scribbled graffiti, written in Spanish but which I will translate into English because they are speaking to us:

“This is OUR Mexico.”

“Get out, tourists.”

These are not the kinds of places you stop to take pictures, otherwise, I would show you.

Of the hardest, most painful things which have happened in my life, I used to think they struck out of nowhere. This kept me in the role of victim. The longer I live, the more landscapes I traverse, the more beings I encounter, and the more agency I come to take in my own living, I come to suspect it is a matter of not knowing how to read the signs. Now, instead, I don’t always necessarily avoid these places, but when I do have to go through them, I tread differently.

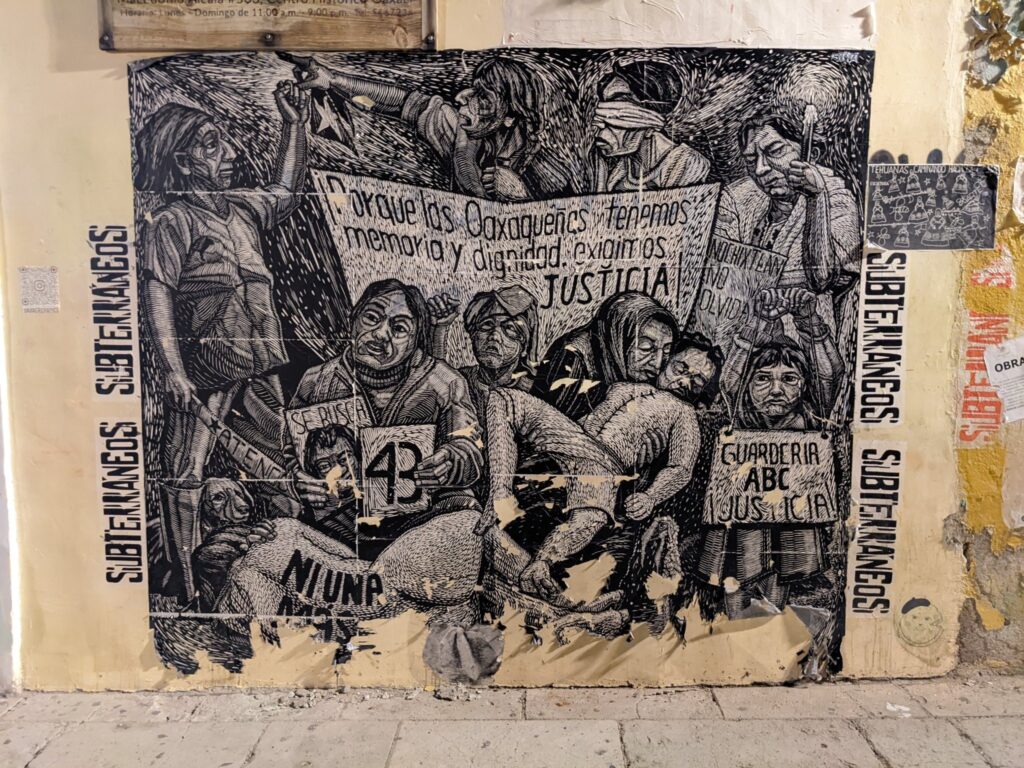

The juxtapositions of Oaxaca are reflected in its art, specifically the muralism and grabado. I’ve already written some about encountering both along the way but, like the smokey flavor of the mezcal, there was a depth and fusion still evolving. ‘Fascinated’ would be to put it lightly.

In the heart of the city, the message was more cultivated and roots which we could safely explore. In this way, and again at the suggestion of our friend Cari, we ended up at a Grabado art collective. The heritage of Jose Posada lives on through the ink stains of these creatives. They, in turn, were taken with Scott’s bike, parked out front.

We had been overjoyed to overlap journeys with a fellow with so much mileage and reflection. He has contributed to a number of bikepacking routes and is healer of wide travels and renown in the community. Neon had been telling me about him for weeks and we were excited to share time and stories. Of the few bikepackers I’ve shared my doubts with, he was the most receptive and understanding and this went a long way toward affirming and assuaging. He also helped reintroduce fun by adding an outside element to our longstanding partnership. Together we explored the street art, a few of the eateries, textile markets, and local fruits.

I took a day of not speaking in Oaxaca. When I stay put, I like to do this a couple times a month. On days when I am around people, I still communicate, I simply make more intentional time for stillness and explore different methods of communication. It’s a great invitation to evaluate what is worth the effort and what is not.

On this day, in the market, I bought a bag of 5 avocados without a word. A little later, I stood watching a young man on a step ladder fastidiously airing and arranging dried peppers, one at a time. The look of concentration on his face was profound and I was fascinated. I was watching art unfold. It was love he was expressing, to each precious nightshade.

Abruptly, he looked up, across the market, and straight into my eyes. He was defensive at first, then a flicker and a small smile. I like to think he saw my utter admiration. He nodded his head slightly. I bowed mine deeply before turning to run after my friends.

All in all, the 4 days we spent in the city were fulfilling and not nearly long enough.

Leaving Oaxaca, our progress remained slow, as there was much to see. Our first stop was only about 12 kilometers down the bike path, the Ahuehuete Arbol Tule, Testigo Milenario. Believed to be over 2000 years old, this Old Man of the Water would have been a sapling when the Zapotec people had elaborate irrigation systems throughout the region. Indeed, they planted these trees ornamentally and devised waterways to sustain them.

Now, he still stands, as the widest identified tree on earth and the descendants of the Zapotec cultivate the gardens, charge visitors for the privilege to meet him, and truck in much of his water. Neon noticed thirsty roots below knobby knees had broken through the sewer walls beneath the grates to steal some extra sips.

YouTube video link: Tule Tree

Following on up the Tlacolula Valley, it was a lovely, flat ride on farm roads, where shepherds moved their flocks amidst the cactus and agave. Anyone on a mountain bike could have a good time of it, depending on how the winds are feeling. We stopped and played for an evening at the Dainzu ruins, having the grounds to ourselves. It is an opportunity and feeling I hope everyone who visits the region can find!

The next day we made our way up the road to the Yagul Ruins, which was populated by local families out for a stroll and folks exercising, though unfortunately the UNESCO world heritage site was closed to visitors Thur-Sat.

We were not terribly off-put, as most of the information I had found was from a graduate school paper written about the neighboring Caballito Blanco Mesa. We spent the rest of the day pedaling and scrambling 4 km around the mesa. We found a few of the pinturas rupestres, we climbed around in a couple of the 500 caves, traversed the fields which the study had pointed out threatens the historical integrity of the site, we rode past the municipal dump established right on the boundary line of the site.

Here again, comparisons and connections with the ancient ones abound. On the one hand, we can judge ourselves disparagingly for how we go on about living without regard to history. On the other hand… the face of the mesa is emblazoned by its most famous painting, ‘El Candelabro.’ For all intents and purposes, a billboard to ancient travelers of the site. A place to come and rest and eat. Playing in them, it wasn’t a stretch to imagine the caves as ancient hotel rooms. The highway which runs past the mesa, goes over top of where the people originally would have been walking by. Precisely what archeologists are so excited about finding, some of the oldest cultivated corn cobs in the world in Cavo-O14, were. Trash.

In fact, I had been laughing about this very thing as we followed the abandoned railroad into town. Many ideas we of the highest privilege commodify, advertise, and institutionalize or consider revolutionary, are simply the way things are and always have been done.

I was thinking about walking the abandoned railroad out of Argentina onto the altiplano along side the alpaca herding grandmothers, as compared to the ‘rails to trails’ initiatives in the United States. Or #normalisebreastfeeding, wear your baby, co-sleeping, home births, multi-generational living, to everything I had seen through Bolivia and Peru. The Slow Food movement, shop/eat local campaigns, grassroots organizations, to, simply how things are done when the reaches of your world extend about to your valley’s edge.

A few examples closer to home were Europe and America making a to do about entomophagy (eating bugs) as a potential way to alleviate demand on beef/protein market when chapulines (fried crickets) are another of the experiential musts when visiting Oaxaca. Or for me personally, the rise of attention to human powered travel. All these things we are having to find our way back to by the means to which we have adapted ourselves, other never lost.

Even something as straightforward as coming back around to prescribed burns, helps me grasp at some inkling of why indigenous voices in realms such as Land Management policy makes so much sense. It is not a matter of giving them a seat at the table, it is a matter of us coming back around and sitting down at the table where everyone else already is: the cactus, bees, trees, seas, rooted cultures, and practicing listening.

Our final stop in the valley was the pueblo of Mitla, on the historic site known by the same name. The Nahuatl name Mictlán was too much for the Spanish so they called it Mitla. Mictlán meant the “place of the dead” or “underworld.” Its Zapotec name is ‘Lyobaa’, which means “place of rest.” Of course, the Catholic did not much like this concept, so they called it ‘hell’ and pulled down much of the stonework of the city to build a cathedral directly over top of the opening where the Zapotec believed the Lord and Lady of the underworld would come through. By their own reckoning, sealing the gates of hell.

Today, the cathedral and a street market cleaves the gated ruins in half. Fringing the pay site there are also municipal ruins of similar structures, though most of the remaining paint and the most detailed fretwork is within the site. There is also a vast underground network, no longer open to the public due to COVID.

One of the most unique aspects of this site is the fretwork and friezes. In these geometric designs, the individual stones are held together without mortar. Elaborating off of six different patterns, seeming to have indicated messages so clear that even a Zapotec child would know what they mean, are lost on us today. Within these designs, combined in ever more intricate designs impart greater meaning still, though, even as I eaves dropped on the many tour groups milling about, interpretations vary.

I also watched the various guardians. The vultures always soaring above these sites, bulbous biznaga cactus which Yesenia told me can take 150 years to grow, the sacred Fig Trees, the Spanish Sword Agave. They all helped me to balance out with the numbers of humans flowing through.

After wandering the sites, we stepped aside to enjoy lunch on the rooftop overlooking the site at Raices de Maiz. The owner was our server and, thrilled at our interest and that I spoke Spanish, he told us about the 5 kinds of corn, introducing us to the 3 of them he had. He also taught us about the mother of corn, teozintle, and many other stories. As we finished the meal ( tetela de maiz negro con cecina, a nopale, and a maracuya mezcal drink) he presented us with a black and red bound book in which he collected messages from visitors. It was our first trail register of this leg of the journey!

That afternoon, by the best of fortunes, we caught the last collectivo van going from Mitla to Hierve el Agua, another very worthwhile site. The young man driving was from the small community who live in, hold, and work the valley and I learned a great deal. He told me about their elders, who can still tell which years will be bumper crops and which years it is better to conserve energy and resources. I learned about the depth to which they dig their wells and what they make their dowsing rods from. That a human hair, left in the sacred waters will calcify into a solid within a month. How often they clean the pools. Why they shut the valley down to visitors when in conflict with the government.

In turn, I told him the road he drove over every day was the same elevation of Machu Picchu. He couldn’t believe it but it was true and he seemed very satisfied to know that.

The falls themselves are calcium carbonate deposits from a relatively small amount of fresh water bubbling up from springs (ergo the name in Spanish meaning “boiling waters” because they burble, though are not hot). The Zapotecs over 2500 years ago were in on it and built a network of irrigation systems (the only example of canal lining work in Mesoamerica) and terraces to funnel what were considered sacred waters.

I was surprised that they still allow bathing in the pools and it almost made me regret not having come earlier, though we had very much needed our afternoon of short rest. The van driver had explained, with a hint of pride, that his community give some of their water to the falls, to keep the pools filled to satisfy the desire of visitors to swim in them. We discussed the honor in taking part in a system of give and take.

And, to that, the next leg of our journey would be a wide diversion from the plan. Rather than staying through the central mountains, we had become concerned enough about some rising ire of the indigenous communities both in the wake of COVID and the new National Guard rapidly building bunkers on their land, we would divert our route to avoid the area entirely, dropping down to the Pacific and then climbing back up and into our final state of Mexico, Chiapas.

How to get involved:

-Contribute and join the journey with monthly support on Patreon.

-Make a 1 time gift via PaPal to itineranthughes@gmail.com

(All proceeds go to the Odyssey and at least 10% is given back to communities along the way)

-Subscribe to receive weekly stories at the bottom of page here.

-Like and Follow on Facebook.

-Follow on Instagram.

-Subscribe on YouTube.

-Follow on Twitter.

Comments (6)

“How much you can explore and learn is limited only by time and curiosity!”

Thank you for sharing the harvest of your curious explorations. I know it is an extraordinary labor of love to turn these experiences into richly-textured text that allows others to participate and learn.

I am listening!

One can never really understand beauty without seeing the underbelly of destruction and ruin

Truth!

Comploiments. I’d sort of lost your blog, and a coupla times wondered how you fared with Covid…

Look forward to your next posts… ??

We hunkered down for COVID starting in March 2020, not wanting to risk the health of the folks we were meeting in Mexico. We resumed movement in September 2021 once we were vaccinated! If you subscribe to the blog, the updates should come straight to your inbox! We’ll be catching up on the rest of bikepacking Central America and then start in on canoeing the Arctic Drainage. Thanks for following along!

Thank you for keeping alive the spirit of adventure… ??