“When you look at the face of Canada and study the geography carefully, you come away with the feeling that God could have designed the canoe first and then set about to conceive a land in which it could flourish.”

-Bill Mason, Path of the Paddle

The “So You Want to…” are a series of retrospectives by Fidgit from across Her Odyssey. They are intended to help provide an overview and starting point for future travelers’ long route dreams. They aim to align realistic expectations and point you in the right direction to do your own planning.

We owe the bulk of our preparedness for this section (literally the very boat we floated in, the boots on Neon’s feet, and the paddle in my hands) to Keith W., for his experience, patience, diligence, and sharing his passion for canoeing.

Grounding and buoying thanks to Tour Guide and Wife Tracker for being our home in Canada. Arno and Elaine Birkigit and their whole clan made this canoe trip possible by being our base, portage support, and so much more. Also to TA & Marian, Lyn Elliot, Julien Cossette, and the Parks Canada folks for sharing routes and beta. And to everyone along the route who helped orient us both to the ways of the water and the locals.

Route Overview

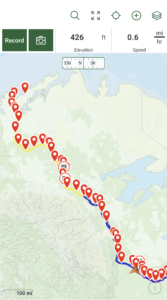

From May 24 -August 24, 2022, we canoed just over 3,000 km of the Arctic Drainage, from Hinton, Alberta to Tuktoyaktuk, NWT.

The waterways were: Athabasca River, through the Peace/Athabasca Delta, a corner of Athabasca Lake to the Slave River, onto the Great Slave Lake, then onto the Mackenzie River and out the Mackenzie Delta onto the Arctic Ocean.

There are a couple of cities, a number of towns, a few dozen smaller settlements, and hundreds of camps and cabins along the water’s edge. You’ll pass seasonal fishing and hunting camps every day, will pass a town or settlement at least once a week, and on each river will encounter a city.

The route is not challenging because of rapids or white water, rather the difficulties are posed largely in its relative remoteness, sun exposure (remember, Land of the Midnight Sun), and wind. We passed through about a dozen class I-II rapids. Most are easily avoided navigating past them on wide, flat water but, same as with the barges, you have to be paying attention and planning, even when the day has dragged on. The lakes and open bodies of water may well present the greatest danger depending on the wind’s temperament.

Planning Resources

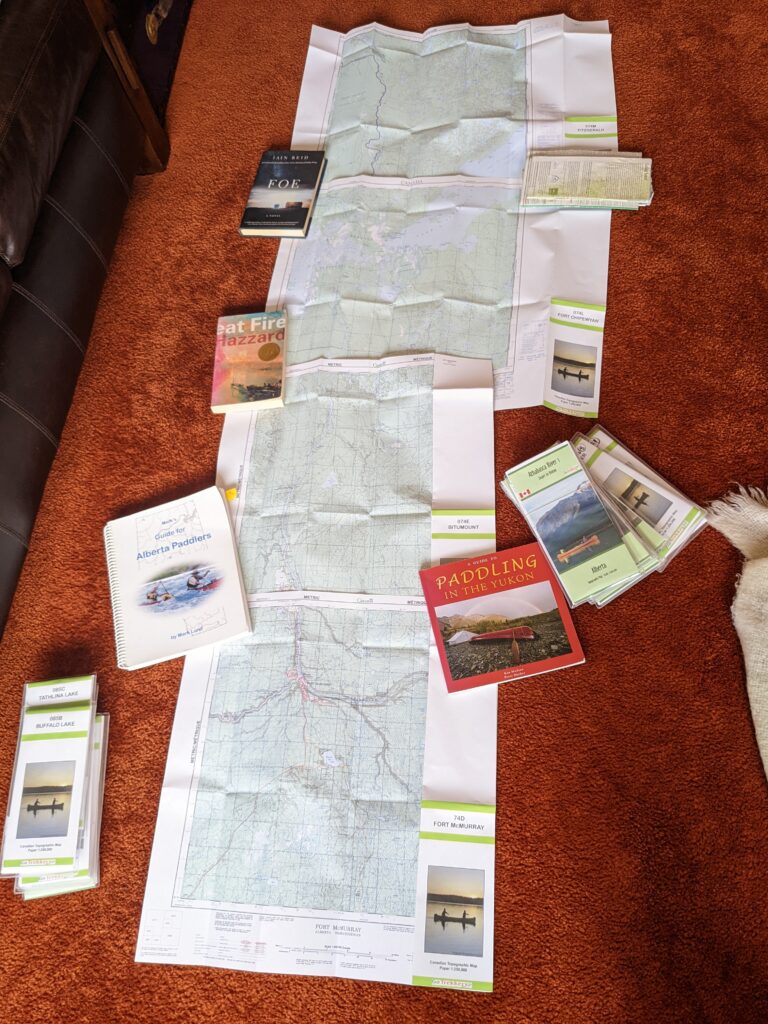

Mark’s Guide for Alberta Paddlers– An excellent, detailed, easy to use guidebook with sections covering specific lengths of river and routes throughout the province. Highly recommended for anyone who plans to paddle in Alberta. This was our primary text source for planning the Athabasca portion.

The Mackenzie River Guide– This is the go to guide for paddling the DehCho [AKA- Mackenzie River, AKA- the Big River]. A responsive and passionate author who is currently working on an update!

TA Loeffler’s Blog– She and and Marian Wissink of #paddlenorth did this same route in 2018. Her blogs give you a good taste of what to expect when you show up whole hearted and humble to the experience.

Canoe North– go to site for Mackenzie River planning. You can rent gear and get an overview. This was my starting point for planning. Considering shipping and travel costs, if you don’t already have a boat you are attached to, renting one through them makes sense from both a logistical and financial standpoint.

Canadian Canoe Routes– I lurked on these forums and threads for months. The wealth of experienced paddlers, differing points of view, and specific information about boat types, paddles, and rapids were helpful and amusing.

Go Trekker Maps– These are a great map set which cover the entire length of the journey. I even got compliments from local bushmen when we bowed our heads over them together.

Bill Mason Path of the Paddle– This book is technical instruction turned into poetry by the author’s deep and abiding love of the sport. He tells parables, and offers grounded guidance. A reviewer on GoodReads put it well:

“This is an almost perfect book – Bill Mason’s love of the craft shines through homey but well-written prose, while his descriptions of canoe technique and rivercraft are generally clear and easy to follow. He obviously writes from a wealth of experience, which translates into solid advice without becoming needlessly dogmatic.”

If I ever get to have my own bookshelf, I would want this one on it.

There are also a ton of fascinating historical accounts as well as plenty of other blogs and articles from more recent voyageurs affording views from different vantage points and skill levels which can be fun to read if you have the time. I enjoyed Charles Mair’s journals, and there are plenty of texts and records of Company men such as Alexander Mackenzie and his 1825-1827 expedition led by a Chipewyan guide.

All of these waterways are established travel corridors since before storied time. Glaciers, birds, bear, ungulates, and First Nations peoples established the way. It’s been so long traveled by human standards that matters are circling back on themselves. For example, the river name ‘Mackenzie’ is shifting back to its Dene name, ‘Deh Cho’, meaning ‘Big Water’. You will hear all these names and more along its shores.

What skill level do I need to tackle this?

I would recommend this route to folks with extended survival competencies and at least some paddling experience. We were both pretty high in the former and relatively low in the latter case.

Ex: I had done a 10 day canoe trip in my youth and Neon and her sister used to go out in an aluminum canoe as kids; also, she had taken a sailing course in college. We both had ample rafting experience, including a month guided on the Rio Maranon and 2 months independently sea kayaking the Caribbean coast of Central America. So, I might be underselling our experience but canoeing is a travel unique unto itself and should be approached with diligence and humility.

That said, the water is generally calm and some stretches of this route are used by university and youth organizations to acquaint young folks with life in the bush. Of the other long paddlers we met, they were all on the Big River [Mackenzie] stretch. Most skilled canoeists prefer the more exciting, scenic rivers such as the Nahanni (a UNESCO World Heritage Site!), Arctic Red, Liard, or any of the other gorgeous arterial ventricles which feed the network of the watershed.

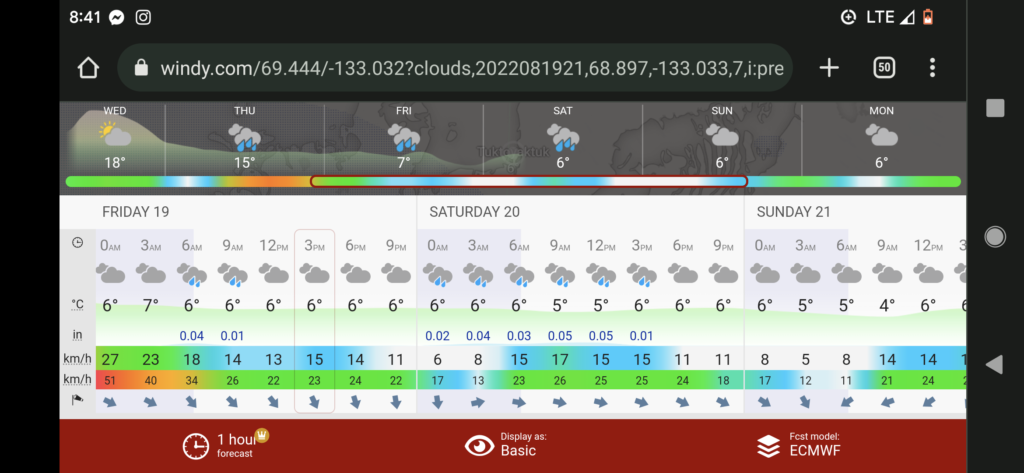

“Being able to read weather and wind directionality, or being able to learn how to read it,” is Neon’s advice. That and, “Knowing what you don’t know is just as important as knowing what you do know.” She said in her best bumper sticker cryptic Matthew McConaughey impression.

Reading big terrain and weather will be more often applicable than white water skills. Having the fortitude to withstand days of sun drenched drudgery and the curiosity to keep your mind and spirits up are a necessity. As is a previously established, trusting, relationship with whoever is in the boat with you. Even a strong relationship will be strained under this prolonged exposure.

Of course there are a series of hard skills one should be acquainted with before she heads out: Basic paddle strokes, how to balance weight in and affix gear to the boat, what to do if you get swamped or flip, when NOT to put your boat in the water, etc.

Then there are the ones you will acquire along the way: reading the trees and terrain for likely camping sites, collecting water from clean side streams rather than your silty highways, where the currents pillow and spin across the wide flats, camping away from the mouths of streams because that is where moose, bear, and everybody else come down to walk their perimeters or get a drink.

Above all, what you need to make this trip is a willingness to “figure it out”.

What kind of boat should I get?

I’ve spent enough time amongst Canadians to know better than to pretend like someone can answer this question for anyone else. This article ‘Choosing the Right Canoe’ gives general bearings.

We were fortunate to end up in a Dagger Venture 17’, made of Royalex. We purchased it third hand from a Scout Crew who acquired it from a local college but because of the material, this boat can withstand a great deal and be repaired from even more.

We also adapted our boat to have a spray skirt. This helped reduce how much water came into the boat on choppy days. It was helpful but not a hands down necessity except in a pinch.

Some helpful parameters we were given:

- Something around 17 feet long for 2 people

- a touring canoe

- It’ll be mostly flat water so something that tracks steadily is preferable to something responsive

- Consider your material (fiberglass, Kevlar, Royalex)

When should I start? What is a realistic timeline? How much distance will I cover in a day?

The start dates of folks who did the full length ranged from May 15-June 9.

You are aiming to start as early as possible so you don’t end up heading into the Arctic as the autumn storms start heaving down. Ideal is to catch the snowmelt, but in our case, the snowmelt wasn’t coming down by late May. Jasper Lake was an expanse of sand dunes with big horn sheep traversing them. We ended up at Hinton just below the pulp mill before we found water reliably high enough to put in.

Another good indicator to watch is the Break Up, an annual event along the northern rivers. In 2022 breakup on the Big River didn’t happen until May 9. I’ve heard its a sight to behold but can imagine no reason you’d want to be anywhere near it in a canoe. Cabin Radio is a great resource to take a pulse on the north in the months before launching.

A realistic timeline is to give yourself about 3 months for the entire trip. Our paddling ranged between 7-125 km in a day, with comfortable averages between 35-75 km per day. It all depends on the speed of the water, temperament of the wind, and how diligent you are feeling about paddling that day.

Will there be rapids? What about portages?

There were two major portages to consider, though that may not be the right name for it since you do not necessarily have to carry your boat, as both are along areas connected by roads:

- Athabasca – Ft. McMurray. ~300 km

On this stretch, the Athabasca runs the bottom of an ancient canyon hosting a series of rapids in Grand Rapids Wildland Provincial Park. Grand Rapids is a class VI. From there to Ft. McMurray are another 8 III and < rapids. I would only recommend this to experienced groups of Expert paddlers with several decades of practice reading and navigating big water. - Fitzgerald – Fort Smith. ~27 km

On the bend around these two communities lie a world famous series of 4 rapids: Pelican Rapids, Rapids of the Drowned, Mountain Portage and Cassette. White water enthusiasts gather here early each August for Slave River Paddlefest.

Hitching around or walking this stretch is facilitated by locals who often drive this jaunt and are known to generously offer a lift.

How fast is the water?

Our experience was moving about:

- 3-5 kph across the big bodies (deltas, lakes, and Arctic Ocean.)

- 5-8 kph on most of the rivers

- A few quicker stretches throughout, with one notable 50 km ride where we were zipping along at 12 kph toward Tulita.

What kind of wildlife is up there?

More than I can tell you. Most of this route is framed by Boreal Forest and these expanses know how to keep a secret and fold time. The lands are inhabited by land mammals such as moose, deer, caribou, reindeer, grizzly bear, black bear, wolves, porcupine, bobcat, lynx, wolverine, muskox, and many others.

Among those surveilling you from the skies are bald and golden eagles, osprey, peregrine falcon, hawks, migrating geese, and more.

The water hosts world class fishing, as well as: beaver, otter, frogs, and seemingly every conceivable variety of water bird and duck. Loons, cranes, swans, pelicans, gulls, terns,… I could swoon on.

Important to know, most of them are in a family way when you come through, so being respectful and reducing the stress on them at this crucial juncture is paramount to the wellbeing of these species. TBH, part of why they come up here to get away from us. That said, there is little you can do to avoid a goose day-care clan’s escape tactic of littering the width of a channel with diving, bobbing babies and hissing, posturing parents, while one feigns injury and flaps frantically ahead of you.

How to approach food resupplies on river? What can I expect for food access in towns?

There’s no cheap answer here but there are several ways to approach it. Just know, food is expensive in the north, generally because shipping costs as much as the product itself. Your options lie somewhere between mailing resupplies, making food drops yourself, and buying along the way.

We opted to pick up the bulk of our food in sales taxless Montana on the drive up, repackaged everything at our homebase in Canada and dropped or sent 3 major resupplies (Athabasca, Hay River, Norman Wells) and then supplemented with vegetables and snacks from grocery stores and town food along the way. We made this choice because, after 6 years and protracted stretches of nutritional deficiencies we needed specific vitamins, grains, proteins, oils, and fats which would be hard to find at shops in the north (by that I mean Ghee and chocolate).

We shipped through Canada Post. Use the Canada Post Parcel Price Calculator to get an idea of the cost of shipping to the NWT and weigh your options carefully. We happened to do this during a fuel price surge and shipping the boxes cost more than someone hopping a flight.

The hotels who had agreed to hold the packages seemed familiar with the practice when I emailed to inquire. If you use this approach: write your information and estimated arrival date on all sides of the package, have it sent 2-4 weeks before your anticipated arrival, and plan to give them business for supporting you.

In the stores we were seeing bags of potato chips for up to $17 and $5 seemed like about as low as prices went. Some pasta packages were a little less. A can of soda cost around $3-$4. Most food travels up here by barge and if you pull in between stock ups, some of the more affordable shelves may be bare. Though, in most communities, there was both a Northern (a chain) and local co-ops who usually feature more reasonable prices and fresher veggies and the folks were always really proud of them.

Towns with year round road access had lower prices than those reached only by plane or boat. We carried both cash and credit cards. On some occasions, phones in town were down and it made everything far easier to be able to pay in cash.

What’s the crux?

Besides deferring human ambition to the elements, such as wind, cold, wild fires, storms, and sun, I’d reckon the most dangerous stretches of this paddle are those on large bodies of open water. Particularly crossing along the southern shore of Great Slave Lake from Fort Resolution to Hay River. Or across the final 35 km of open Arctic Ocean to Tuktoyaktuk.

If the wind is coming out of the north (which it usually is), you’re in a pickle. It’s had over 100 miles of open water to build waves which wedge fallen trees into the coves like toothpicks in a pocket. So, if the water is up, you have waves and currents pushing you into these messes. In this situation, your stern person has to know how to hold a direction, your bow can not stop paddling, and you need to be able to meet all bio needs in a lurching boat for an indeterminate span of time.

Being on open water in big wind is all of the effort of whitewater, without the advantage of getting anywhere. Our sketchiest stretch was crossing Lake Mamawi in the heart of the Peace/Athabasca Delta. TA had had a straight line of it across the 7 km stretch, but we headed out into what was a building headwind and it was well over two hours of relentlessness battling, sponging, paddling, balancing, and bailing.

[Wind is *usually* calmest late at night, early morning.]

“White people are always coming up here and finding ways to die,” two women playing in kayaks on the rapids near Fort Smith told us one day. Pushing out onto the Great Slave Lake and getting winded in to a fishing point 120 km shy of Hay River, the locals who came down to watch the water told us about many such incidents. Most recently of outsiders, Thomas Destailleur drown in 2019 in exactly the stretch we were considering.

For some of us, swallowing our pride is the crux of any grand endeavor. We ended up hitching around that stretch because we didn’t have the indeterminate time span which might be necessary to wait out the weather.

Connection with Locals?

Interactions with folks has the potential to be as fulfilling as the solitude offered by this route. Many of the locals are descendants from he peoples who signed treaties with the Crown, before Canada even existed. Thus, once you are in the Northwest Territories, you are very much in someone else’s territory.

This route travels through several First Nations and other Indigenous folks’ Territories and Treaty Lands. The very people who led Alexander Mackenzie and many other explorers through these lands, still populate and tend it. One way we see this is in the River Guardians programs.

Proceeding duly and with receptive respect, matters. While the tribes rarely require passports or other paperwork and stamps to cross their land, it is appropriate to reach out and let them know of your plans.

We owe thanks to Micki H who helped orient us to the peoples we would meet. A brief orientation from her work:

“Along your route you’ll cross three broad Indigenous territories: first, the Cree in most parts of Alberta; next the Dene (pronounced deh-neh and meaning “people”), which you’ll begin to meet in the far north of Alberta and whose territory continues across most of the NWT; and finally, the Inuit (pronounced ee-noo-eet, also meaning “people”) in the far north.

You’ll also cross the territories of several groups of Dene. They are, in the order with which you’ll meet them:

- Denesuline, also known as Chipewyan (pronounced: deh-neh-soo-lee-neh and CHIP-eh-wahn)

- Deh Cho, also known as South Slavey (pronounced: day-cho)

- Sahtu, also known as North Slavey (pronounced: saw-too)

- Gwich’in

You will then cross into the territory of the Inuvialuit (pronounced: ee-noo-vee-AH-loo-eet). This is a group of Inuit located in western Canada.

The above names are in Indigenous language followed by their English/colonial name. You’ll hear these used interchangeably.”

She put together a list of contact points at the communities along the riverways and I wrote an email to each, giving them anticipated arrival window, intent, and asking if there is anything we could offer or should watch out for. What we got in return were generous welcomes and invitations to community events. As will unfold in the stories in the weeks ahead, their hospitality and generosity are rivaled only by their reflections in Patagonia.

What kind of footwear should I bring?

We wore insulated mucking boots for getting in and out of the boat and tromping around on river banks. In camp and in the boat we wore trail shoes. Some days I spent barefoot enjoying the mud and cold water between my toes as the sun beat down but on the cold, wet days, having dry feet makes all the difference in the world.

What kind of tech did you carry?

Garmin inReach, Garmin 66i, 2 cell phones, 2 reading tablets, a backpacking solar panel, 4 battery packs in various sizes, and approximately 15,007 cords. Don’t ask how or why. They seem to operate under the same principle as Ziploc bags. You have either not enough or far too many. I don’t make the rules.

We relied heavily on our inReach and summoned daily weather forecasts. Even though we found the DarkSky forecasts to be generally reliable out to 3 days, watching how the weather shifted in the forecasts was just as helpful as the forecasts themselves. Our Garmin 66i provides satellite imagery and helped allay my panic that the boat would flip and we’d be somehow separated and lost deep in the bush on opposite banks of the river for an extended period. Thus, separate trackers and individual bike tire tube wrapped firestarter kits in our PFDs.

The GaiaMaps* ‘Backroad Mapbooks Canada’ overlay is accurate down to the islands which shift around in the river. (Their Native Land Territories overlay paints a colorful story of interplay, and the fire overlay would update when we had connectivity, mostly around the communities).

*Link to a discounted membership

Do I need a drysuit?

With every new sport and season there is some big ticket piece of gear I get all worked up over and drop a boatload of money on only to realize at the end of the season, I never touched the thing. That would be our drysuits. If you are water familiar and employ a dry top as part of your routine, rock it. Besides that, you probably won’t use it, as the predominant heat means steaming or stewing in a sack of your own juices.

In conclusion,

here’s our gear list

Whittle it down to suit your style, we were definitely carrying more than necessary.

If you have any general or starter questions, drop em in the comments.

Hope this helps and thank you for reading through!