May 24-June 6, 2022

The first stretch of canoeing was on the 1200 km long Athabasca River. We drove up the icefields Parkway to our intended put-in near Jasper. This route paralleled what we had walked on the Great Divide Trail last autumn.

Passing the Athabasca Glacier, where the river we would paddle is born, we paused for a moment of admiration, reflection, and an ‘usie’. Glaciers are the kind of trend setters I admire. They opened the paths and paved the way for the rest of us. I’m no Mary Vaux or Fanny Bullock Workman but I respect their work, passion, and tenacity, for helping us understand the story of these giants.

I’ve gotten to live, climb, run dogs, and clamber around inside of glaciers. On Her Odyssey, we’ve crossed the globe on their heels and it’s an honor to stand in acknowledgment and reverence at the tail end of their latest run. From the edge of their Antarctic domain, through the last pockets of hold outs in the tropics, soon to connect to the Arctic Circle.

I recall one particular fall-to-the-ground-giggle-fit on the GDT at a pass just beyond 3 Isle Lake where the rock had made the ice masses turn and bank so hard I could hear the echoes of that cataclysm as a cartoonish “peeling out” sound effect.

We’d identified a couple put-in options but the season had different plans. When we got there, Jasper Lake was a sweep of sandy hills with a troop of bighorn sheep ambling up the middle in a ray of sunlight between clouds. The vision left me simultaneously forlorn and awestruck. I knew the adventure had begun because nothing was going according to plan.

We ended up putting in below the pulp mill in Hinton. Keith and Heather paddled with us to Whitecourt and it was hugely helpful to learn from their experience and methods as we adapted to a new landscape. Black spruce like wet ground and are not a good spot to look for a campsite, which sides of the islands are more likely to harbor protected camping spots, and thunderstorms are more likely in the afternoon so an early start behooves you.

It was also just plumb fun to share miles with another wilderness-wise duo. They seemed to grow younger and more playful the longer they were out. By 3 days we moved with the same energy as a pack of feral kids, sharing our candy stashes and exploring hidden wilderness around the neighborhood. On the final morning, we awoke to bubbles.

In those first few days we met a lot of locals: loons, moose, beaver, bald eagles, geese, mergansers, white throated sparrows singing “Ohhh, CanadaCanadaCanada.” Even a couple of human families out for a ramble in their Gators. They shared fresh fruit, a bag of sunflower seeds, and stories. I was impressed that, in the time it took me to pitch our tent, they had made benches and a stack of firewood appear! There is a relationship between Canadians and their chainsaws, the likes of which I have not seen since deep in Patagonia.

From Whitecourt we paddled on alone and my internal calibrations went haywire. I felt giddy and trepidatious. In a hurry to get nowhere. Racing forces I cannot see, according to a mutable timeline, across a landscape I did not know.

That first night camping by ourselves I felt myself seeping into the solitude. A relief I had not felt in many many moons. I spread out on the ground and lay there until I could touch stillness. I roared, sang, danced, hooted, stood barefoot in the mud at the water’s edge watching a group of ducks bathing.

After dinner, clean up, and packing in camp, I settled into my little camp chair at the riverside to journal and watch. A mother moose and her calf crossed the river. She swam and strode the sandbar in the middle of the river calmly keeping her calf in the protective eddy of her body as the wee one struggled for dear life. Later a black bear crossed, going the opposite direction. As I zipped into the tent I heard another large, pawed local patter to the crossing. I don’t mind this kind of traffic.

The stoke factor, desire to set good routines, and Invisible Forces race had me leaping out of the gate. It wasn’t until one of those interminable “looking for camp” stretches that drag out for 3 hours at the end of the day that I realized we’d need to pace ourselves better. On this day, we’d been aiming to make camp early (by 2 pm, so we could rest) but didn’t find one until 5 pm. Whereupon I promptly fell asleep for a 2 hour nap, woke up for dinner, then slept another 10.

Wondering why I was so tired and also couldn’t move my arms, Neon pointed out, “we’ve paddled every day for the past 12 days.” We were both noticing that we could not sleep with our arms bent, nor on our sides. Still, I consistently enjoyed the deepest sleep in years, which in and of itself is reason enough to love a sport.

I had a creeping nerve tingling which turned into numbness in my left arm and which sometimes shut it down completely. I would manage the angles of my stroke relying on bone and muscle to do their thing while the nerves went on strike. It was disconcerting and unpleasant but I tended it with all the resources we had and after about 6 weeks it faded.

We had been anticipating that wind and weather would routinely impede progress and I was relying on that to pace us but darn it, we were having a run of incredible weather!

I’d figured that TA’s average of 39 kms a day (50 kms per day on river) would put us into Tuk before the Keith Deadline of, “be done before September”. (That is when the big storms start rolling down). We were consistently above that average so Neon suggested we temper the enthusiasm to push our boundaries with easing up.

On top of good advice, Neon she also introduced me to using a cork ball to relieve the arm and lower back issues. “Balling so hard” became a part of our evening routines.

Another delight was staring at trees. The Boreal (or Taiga) forest is a fascinating, uncomfortable place. Baba Yaga and Sasquatch territory.

The mystery and tales fueled by how relatively little is known about the earth’s largest terrestrial biome. This habitat represents over 30% of the earth’s forests and covers 17% of the total land surface. The boreal forest is the ring of hair around the permafrost bald-spot at our planet’s dome. It is also disconcertingly timeless in there. It didn’t feel ancient, just expansive enough that time as we reckon it wasn’t relevant. The trees didn’t strike me as even a couple hundred years old.

My gut check was confirmed by this Natural Resources Canada piece which pointed out the boreal, like us, had to wait for the glaciers to clear out first.

“Canada’s boreal forest is often portrayed as one vast tract of ancient, pristine wilderness. Although the boreal region itself is ancient, boreal forests are made up of trees that are mostly relatively young compared with some trees that grow in more temperate climates. Nor is it all the same—the boreal forest is a complex and heterogeneous landscape of different ecosystems and species, continuously shaped and renewed by a cycle of natural disturbances, as well as human activity.“

One evening, 4 days away from anywhere, as we stared into the treetops over dinner, I commented that the tops were turning yellowish brown. We played the time honored slow traveler’s game of ‘Speculation’ and quickly pulled out the ‘Catastrophization Extension Pack’: The heat and sun which was baking us, must also be baking the treetops. It’s a blight, like the pine beetles who have been rampaging through my home mountains for the last few decades and who we also saw lurking around Banff and Jasper.

Then I remembered the binoculars in my Granite Gear Stowaway Seat Pack and we moved into round 2 of the game, ‘engage available resources to gather more information.’ Upon inspection we realized the trees were coning, the turning color was their terminal buds.

We were heading into the bowels of a massive, randy, forest! I felt like Miss Frizzle, except instead of driving a Magic School bus we were in a green canoe striated by yellow pollen waterlines. Pools of it eddied on the river surface, gathering up into bowling balls of frothy suds that I liked jabbing with my paddle. I noticed Neon subtly steering us toward good ones.

Besides education and entertainment, this made for constant allergies. When we weren’t sneezing or making juvenile jokes, sometimes I drifted into a reverie inspecting and brushing off the powdery coating, thinking, “this is the bee’s knees. This is literally like being bee’s knees!”

Another delight of life cycles was that our tenure on the Athabasca allowed us to witness a full season of the family process of geese and ducks. When we put on, the mating pairs were generally on the banks, adamantly and vociferously protecting their nests.

Then there appeared single family units with tufts of 4-8 goslings and ducklings hugging close to one parent while the other shadowed. We tried to steer clear but usually someone would come out to shout at or distract us while the other led the little cluster into cover along the shore where they would practice their diving.

We’d play along, commenting aloud, “oh, look at that violently flapping goose ahead. It must be injured, we’d better follow it!”

There were also large flocks of adults migrating northward. You could almost always hear them coming, it was like a carnival rolling through town and had a similar effect: I’d scuttled out to the riverside to watch the parade.

The water was millpond calm, the V-formation flying low, not more than a meter above the water. I could look down from 5 meter tall bank onto their backs and also see perfect mirrors of their feet tucked against speckled bellies. Even amidst the din of their voices, I could hear the wind between the feathers of their wings. I wished them luck and told them we’d be along soon.

By late June, the family units had rafted up and were swapping kids. There would be 4-8 adults and a gaggle of somewhere between 12 and 12,000 goslings who were now too buoyant to dive terribly well. Instead of being able to just give berth and avoid the cluster, we were now faced with a minefield of downy little butts and webbed feet desperately flapping in the air before they would disappear only to pop back to the surface at some other inconvenient spot just downstream.

The next stage was smaller clusters of lurking adolescents. Then it seemed like the show had wrapped up and left town. I didn’t see them go, though I noticed the absence.

Then, an eternity later, we were abruptly in Athabasca. Arno and Elaine had given us directions orienting by their impressive solar arrays on the river’s edge and, finally with a destination in sight, we dawdled. Inspecting some rocks, a pollen pool, a cute family of ducks (did I mention, the duck clans tended to be much smaller, quieter, and more polite?) I think some part of us was testing whether time had come back into effect.

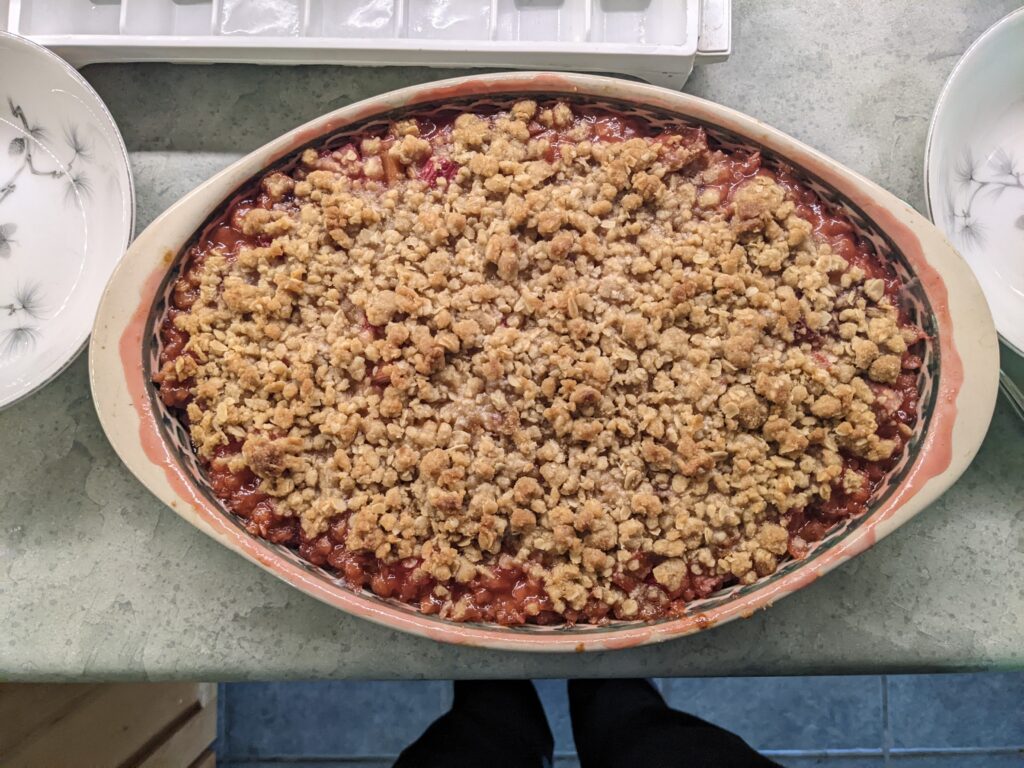

Arno and Elaine received us warmly, fed us well, provided all we needed and more as we transitioned to bikes for the 300 kms to Fort McMurray where they would meet us to put the boat back in the water. I needed to fret over and love on the Arctic Tern (our boat’s name) and Arno taught me much and played patiently. Elaine had made a cobbler I’ll never forget, and the home they had etched out of this woodland was dotted with resting places and gardens which are older than I am.

We were nurtured and empowered.

A couple articles I enjoyed while studying up a bit for this post:

Boreal Threshold

The Great Siberian Thaw