June 6 – 19, 2022

We set off on our bikes from Arno and Elaine’s woodland reprieve feeling goofy and confident. We took our time, balancing covering ground with this opportunity to have my tablet and manage communications, notes, and writing work.

About 170 km into the 300 km ride my rear tire started going flat. A series of scrappy modifications we’d made in Nicaragua had put me back on a tube, which is less than ideal when riding on shoulders where heavy machinery constantly throw wire cord shrapnel. We patched it, then switched the tube for Neon’s last spare, then patched that one several more times but eventually were covering less than 2 km between repairs.

The final flat came on the cusp of a deluge. We were on 63 north, which is predominantly mining machinery. We decided to backtrack a couple kilometers to a rest stop where we would be safer, could meet basic needs, and make decisions. Neon pedaled into the downpour as I walked my bike, carrying the rear tire aloft. Wide load double trailers hurdled head on, spraying waves over my head even as I hugged the ditch. I felt bad for how much my presence must frustrate the drivers and make us both nervous, acutely aware of what an inconvenient fool I was making.

Then, in the matter of a single step, I was in a dry narrow between cloud cells. Pausing to marvel, looking both ways, I found my breath, shook off the self loathing, checked in with Fear, and then gave it all up to the sanctity of this space. By the time I stepped into the curtain of the next cell, I was again an active agent in my own being. Joining Neon in a dank, graffitied roadside toilet which we dubbed our “office”, we peeled off the most sopping layers and hopped around until we warmed up.

Stepping outside under the narrow awning, we munched a few bites of bars and stared down a long column of dense clouds which overlapped our route, thunder boomed and lightning struck. Then, a white pickup truck pulled up. Mike and his crew were contractors heading to Ft. McMurray for a job.

We did not ask for help, I was too ashamed, feeling like I deserved this, having brought it on myself. The crew offered us a lifeline anyway. One I had to swallow my pride to accept but therein again lies a theme close to the heart of this journey: practice setting ego and identity aside to accept kindness and connection.

They loaded us and our gear up and drove on, sharing stories of their travels, aspirations, adventures. They offered valuable advice, echoing Keith’s, to carry all our own water for as long as we could (at least 3 days) downriver from the oil and natural gas extraction sites. I asked if collecting from side streams would be an option but they cautioned against it. We were grateful to have brought several extra empty wine bags which upped our water carrying capacity to about 25 Liters. They dropped us off in a Tim Horton’s parking lot.

Arno and Elaine met us at the park where the Clearwater River merges with the Athabasca, switched out the bikes for our boat, and saw us off with kind words and encouragement. We marveled at how much the river had widened and played our paddles through rainbows of oil slick. This industrial length was the only stretch along which we saw no wildlife, neither the beavers nor eagles who had become near daily companions.

Along with natural oil and gas floating on the surface, we also began to regularly encounter sandbars. At one point we were standing in ankle deep water with shore at least half a kilometer away to either side. Tugging the boat along between fits of laughter and discussing what we’d noticed that we could avoid this in the future. We’d already been issued a citation for Canoe Abuse on the launch stretch when we chose to follow a lesser channel and ended up dragging our loaded boats over rocks through threads of water. We had a long way to go in terms of learning to read the road signs.

We saw more of the same patterns of weather as we had on the ride and a couple times pulled over to wait out lightning strikes. The river banks were also changing, growing tall. We would paddle alongside escarpments which, along with the volume of the river, toyed with my sense of scale and distance.

These factors also influenced our camping methods. We found ourselves gravitating toward already established locations, where hunting camps or cabins stood on small, cleared plots. Again, like Patagonia, this seemed a landscape where wilderness reigned and even abandoned. Even an overgrown, abandoned location prompted a sense of hope and belonging which had us scrambling up the cutbanks half hoping someone would be home, or “out on the land” as the locals phrase it.

Uncertain of protocol, we would pitch camp in a corner of the yard and I often wrote notes of thanks and praise for when those who steward the land came back. I can’t say whether this is a “right” way to go about it, I know some adventurers prefer to avoid the question altogether, instead cutting and crafting their own sites out of the bush.

Singing goodbye to the Athabasca one afternoon we diverted onto the Embarras River, then Mamawi Creek led into the heart of the Peace-Athabasca Delta, one of the largest freshwater deltas in the world. We’d chosen this route because it was the way TA went and seemed to be the most direct route. We were heartened to see orange laundry jugs and red gas jugs tied to branches jutting out of the water along the channel. Again, like Patagonia, locals make trail markers with what works.

The deeper we went into the delta, the slower the water and the more voracious the bugs. We just so happened to make camp one evening at the last patch of (mostly) dry ground before heading into Mamawi Lake. Songs of frogs, birds, and beavers beat the thrumming heartbeat of the delta. We planned for a 3:30 am wake up to cross the open lake Mamawi before the wind was forecasted to pick up around 11 am.

Groggy the next morning we set out amidst the reeds, following channels which we had traced from satellite imagery, otherwise it quickly becomes a maze. We kept running into logjams at the channel outlets to the lake and having to backtrack, looking for another way out to the open water.

Amidst the building stress as we found our ways barred, we came upon a romp of 5 otters. We both became still and dreamy, eaves dropping on their chatter. One stood atop the log flexing a fish in its paws to expose a glistening white belly the same as you might stretch a watermelon rind before noshing into juicy flesh. The others dove, swam and splashed. A stolen moment of play before resuming our search.

Funnily enough, an hour later we had doubled back to that same channel and found it to be our only passable route into the lake, which was already starting to move. We’d been paddling for 3 hours and, anxious to get going, we agreed on a point at the far shore to aim at and forged out into the lake.

Here our inexperience all came tumbling over the gunwales. For starters, we’d not put on the spray skirt because we thought we could “beat” the wind. Secondly, as the winds picked up Neon kept orienting us to drive head on into the wind, which increasingly led us out into the middle and slowed our progress. Thirdly, while we’d chosen a land point, your orientation changes as you cross open water. All in all it amounted to over two hours of furious paddling, stopping only to bail and one time my shouting, “ARE YOU EVEN PADDLING?!” (It would be funny…later)

I’m here to tell you, the only reason paddling white water is fun, is because you are getting somewhere. When you are battling the elements with a glorified ice cream scoop, gaining inches at a time, it is far from pleasant.

We were aching and relieved to crawl the boat into the relative protection of beds of reeds at the far side of the lake, which was now spraying whitecaps. Taking turns holding the boat while the other ate.

It is interesting to reflect, (from a safe, dry, and solid place) at the number of times our lives have been imperiled in the hearts of lands who are themselves threatened by our species. From the peat bogs of the Magallanes region to the Peace-Athabasca Delta. It strikes me as some living iteration of the Golden Ratio.

Once safely in the channels which led to Fort Chipewyan, we began to relax and soon were looking for someplace to eat lunch. Smooth, hulking forms rose out of the water and my heartbeat gladdened and then thrilled. Here we got to meet Shield Rock!

I’ve been reading and dreaming about it for years. Touching the ancient core of our continent. The Laurentian Plateau (and here I had a Lauren in the boat with me!), the exposed heart of our home. I’m munching cheese and crackers, spilling crumbs on some of the oldest known rock on earth.

For the next 20 kms, riverfront cabin homes became more and more frequent, until we were passing ways with motorboats going to and from Fort Chip. One such boat motored close to say hello, tell us we were only 6 miles shy of town. We’d planned to camp on the winter road, where TA had a site marked but when we got there it was a mite damp for our liking.

We were in no hurry to push across the corner of Lake Athabasca between us and town that evening. We prefer earlier arrivals to towns so as to maximize on the day and decrease spending. We were also still shaken from that morning’s experience and the winds had only picked up over the course of the afternoon.

We stuck to the reeds and skirted the edge of the lake to a rocky outcropping where we began to nestle a camp amidst the ledges and pine. A boat came from town and we watched curiously as it picked its way toward us. The lone figure pausing to step out to his bow with a long pole and probe for depth.

Jumbo, an elder of the community had come out to check on us. He’d been the one to say hello earlier and, well knowing these winds and waters, had come across to offer us a ride in to town. We hemmed and hawed. In true northern fashion, he read our uncertainty and addressed it directly.

“If you don’t need help, then you don’t need help,” he put it simply.

“We don’t need help but we’ll see you tomorrow!” I replied.

Just his care and kindness lifted my spirits. It felt like more than enough, just as the flat ground space was a little less than enough for our tent. I slept heavily as freshwater slapped Shield stone.

The next morning, the 3 kms was again a crawl in moderate winds and funny currents where massive Lake Athabasca was drawn into Slave River. Dragging the Arctic Tern into the shallows behind the boat graveyard, thinking ourselves quite discreet, we had no idea the welcome we were in for.

In fact, the whole town knew we were coming and their welcome was unparalleled. It was Treaty Days and the Cree and Dene were taking turns hosting celebrations. Bruce, who had grown up here showed up to take us on a driving tour of the town. He gently asked why we had chosen the Mamawi route, “was it just because it looked shortest on your maps?”

We learned that since the Delta was at a conjunction of three major bodies of water, the direction of the flow in those channels depended on their water levels. Knowing which route to take into town changes throughout a season and is truly a matter known only to those who live there and spend their time out on the water.

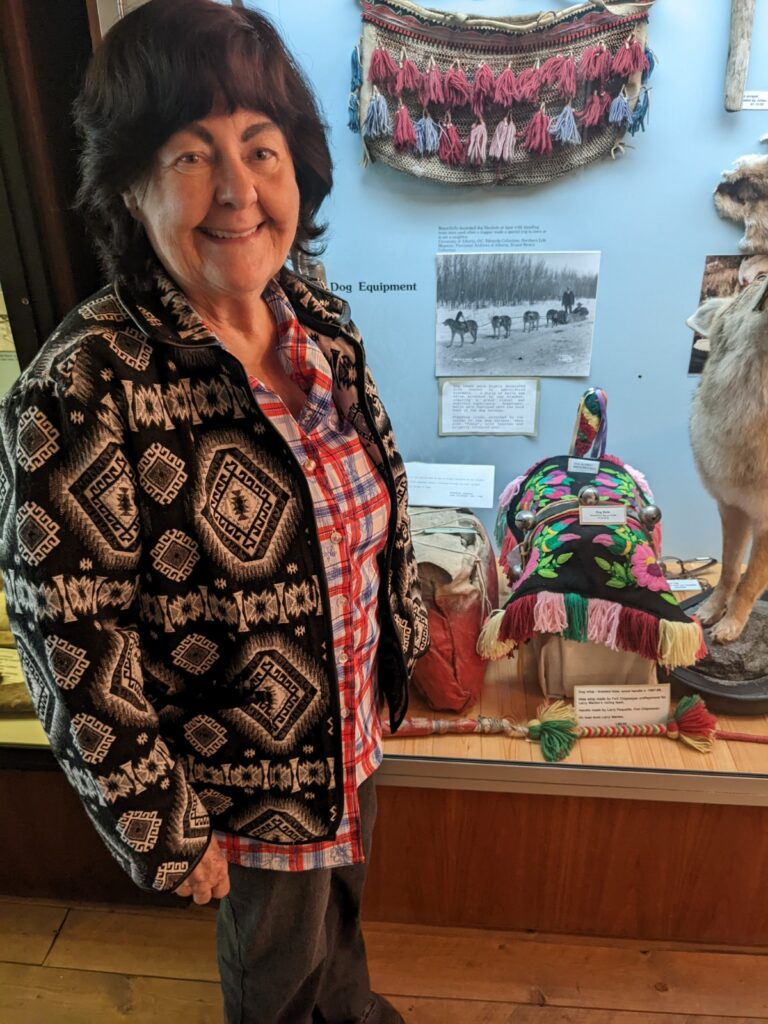

Folks dropped by our tent each day to trade stories and invite us to events. Jimmy insisted we borrow his truck to take showers at the rec center or get out to Dog Head where the games were being held. Jumbo checked on us every day. When the weather turned icky, the community made sure we had a roof over our heads. We spent 4 days enjoying the dances, hand games, feasts, and the Fort Chipewyan Bicentennial museum. This became the first of my favorite communities of the north.

One of the treasures they gave us, was the link to this 15 minute video, telling some of the story of the town. From adopting Canada Geese, to the history. Told by a man who, in 4 days of aiding us, never once mentioned that he had been mayor.

One of Jumbo’s last pieces of advice as we hauled our boat back down to the water was about the mosquitoes. I puzzled over it for the following months, whether it was a tease or in earnest. This little snapshot clarified both his humor and his heart, “whatever you do, let these girls eat a little bit. They’ve gotta survive too…but don’t overdo it.”

Walking up to the rocky outcrop from which Mackenzie set out for his paddle, I sat happily in the echo, feeling just how cared for, guided, and supported the locals of this area have always made explorers feel. Warming us with the wisdom, fuel, and strength to wander the lengths of the world.

Comments (3)

What a treat to dig into the details from the comfort of my warm, dry recliner. Thank you for all your labors to document so we can join you vicariously.

Looks and sounds incredible!!! On the rather mundane side of things I was wondering how long this took the two of you to complete? Like how many days from your starting point until you arrived in Fort Chip?

The opening line is the dates from Athabasca to Chip. All our canoeing posts should start that way so you can figure out times depending on which town you are starting from.

If you are asking when we started Her Odyssey down in Ushuaia, that was November 2015. We did not complete the Expedition until reaching Tuktoyaktuk. Is that what you were inquiring?