July 13-July 25, 2022

Fort Providence- Tulita

Setting out from Fort Providence we navigated our first thunder and lightning deluge. We’ve watched them skirt the river and it was fascinating to be on a terrain so open that you can see every edge of the cell and watch its trajectory. This one struck close enough that we pulled over in the willows, scampered into tree-line, and hunkered among the mosquitoes. Minutes after we were back in the boat, the sun was baking and sent us scrambling for sunscreen.

For the next several days our company was largely comprised of birds. The terns and gulls were none too pleased when we paused on their islands. Eagles watched passively from their nests, sometimes chittering quietly. On this paddle overall, we saw eagles more days than we didn’t. It was an encouraging difference from some of the guidebooks I had read from the 70s-90s which noted the lack of these raptors. We passed Jean Marie community, where most everyone was gone to town for a dance, and only a couple folks were around, working on rebuilding their properties after the flooding.

The next few days, river left was one storytelling landslide after another until we arrived to Fort Simpson, where the famous Liard River pours into the Big River. We spent a day stretching our legs walking around town and joining in for a community feast down at the campground. We continued orienting ourselves a bit to the history of the region. I spent a morning watching the float planes take off and scored major auntie points when I sent a video of them to my nephews. I got my turn at being delighted to find that Dan had sent a kilo of yerba mate for us, thus replacing the most significant of our minor losses to the fish gut bear.

We made an evening departure the next day, my favorite way to enjoy the long twilight stretches. 12 km out of town, we pulled over where a road came down to the water’s edge. A couple were out watching the river and, having heard about us from Carla’s CBC article and Facebook advocacy of our project, we chatted a bit. They generously offered us their cabin, about a mile up a side river and I was again humbled by how cautious and courteous folks are. It being well after 11 pm, we were content to stay where we were and had a sound night sleep.

From there it was only a few days until we were in the company of the striking Camsell Range, which escorted us with a spectacular, undulating wall for well over 100 kms. I was enamored with the face and fixated on the striations so at the next internet source, went digging.

In the type area, the Camsell is a limestone breccia variably silty with some breccia fragments more than 3 m (9 ft) across in a yellow and orange weathering matrix with some thick intervals of featureless lime mudstone. South and west from the type area the Camsell is colour-banded and consists of thick- to medium-bedded orange weathering dolomite and light yellowish-grey dolomite. In the subsurface, the Camsell is formed of interbedded anhydrite and silty dolomite and limestone.”

Between them, the McMurray mountains, and behind them, the Mackenzies, I felt in distinguished company. The cranes and loons too, were becoming more frequent. My favorite night though, was journaling by the river after Neon had crawled into the tent, hearing an owl speak above our campsite, and from across the river, the howling of a wolf pack.

Journal excerpt:

“We’ve paddled alongside rainbows, amidst fog, past yet another forest fire, alongside a trotting bobcat, and according to lore, the island home of a giant muskrat, where we were told to pass quietly and on river left to be respectful.

…

Against the curving sky, the low grade slopes up to the ridges of peaks toy with frame of reference. The clouds flow this way and that, Neon perches her compass on the yoke and watches the wind. Currents braid, bounce and twist within the breadth of the river, easily taking the bank a km away.

Taken together it swallows any chance of orienting yourself. I’ve not been so generally discombobulated and plumb contented in place and time since living on a glacier. It feels like being a mite on the sleeve of someone giving a huge hug. Got mesmerized watching my paddle dip into the water, riffles over top of current; so taken by it that I got vertigo and nearly pitched out of the boat when I looked up again.”

We took a river rest day to wait out weather and got lucky, happening upon a hunting cabin. There was a teepee out back with a metal table, likely for dressing meat after a hunt, based on the bear claw swipes at the door flap.

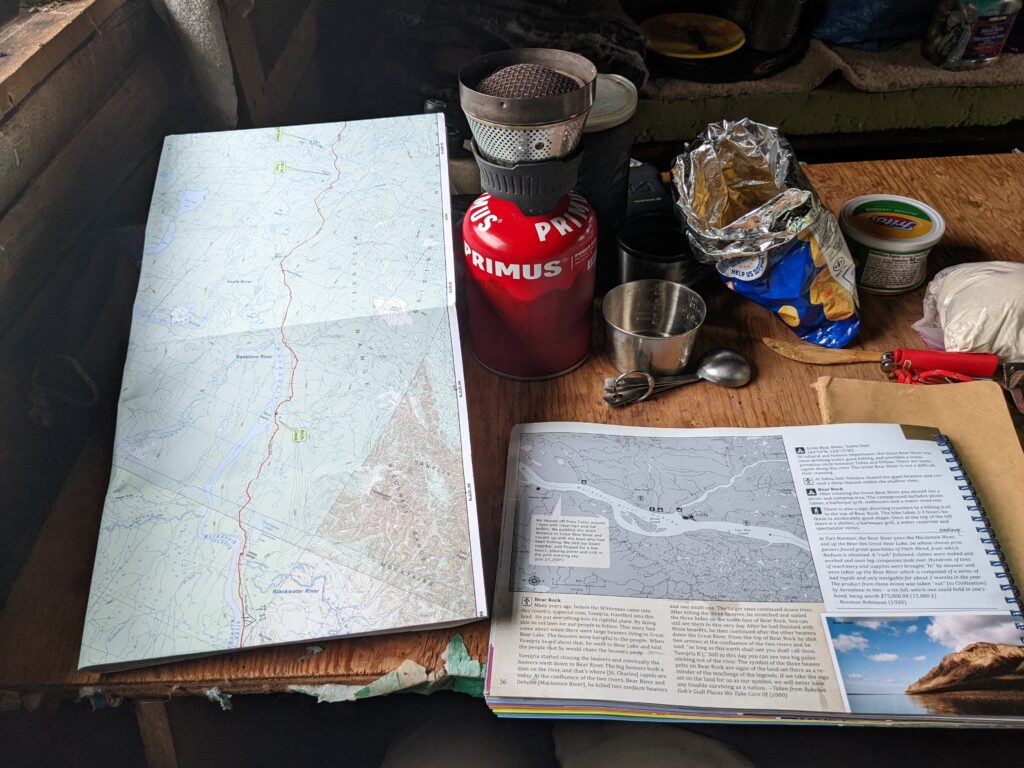

I love these days because Neon makes pancakes, which we slather with almond butter and jam, topped with syrup for brunch. I made a ‘what’s in the barrel’ variation on Heather’s Mexican hash browns for dinner, journaled, and spent the afternoon brushing my hair by the window and reading while Neon cross-stitched and looked over maps. We’re both playing the ‘count down the mileage’ game but not talking about it aloud, yet.

The water level had already dropped too low for us to take the Police Island short cut at a large westward bend. We’d been flying high, going nearly 12 kph through a fun, relatively narrow stretch since the Keele river joined us. As it widened and slowed, the sun seemed to bore down even harder, setting its infinity of sparkling reflections to their job of burning the inside of my nostrils.

Then, Bear Rock reared into view and all the legends clicked into place. A distinctive and ancient cross-roads in these lands. Lore tells of giant beavers, wreaking havoc. The giant Yamoria, hunting and tricking them. Now 3 of their pelts are tanning on the cliff face before us. A site of deep importance to the Dene tribes around here and from which they draw great pride.

We plunked, sweltering, onto the bank near the small dock of Tulita and sat for a while, sun dazed and hungry. We’d seen the town website seemed to be encouraging tourism and the wind forecast on the inReach encouraged the same. It also appealed as a more tranquil pause than a hub like Norman Wells.

Neon made the exploratory foray up the bank to town and I was dozing in the sun when she reappeared, much to my surprise, in the passenger seat with Kimberly expertly swinging the suburban around on the bank sand and mud. Getting out to prod the ground with her toes before executing a doughnut to get us headed back the right way. She’s the hotel manager, unofficial town manager as far as I could tell, and Personnel Center of Town Technicalities and Chuckles.

She made Tulita not just a stopping point, but a gift of time. She proudly oriented us to town and the happenings, encouraging us to go watch an afternoon of Hand Games, a team game of drum rhythm, trickery, laughter, and shouting. It was followed by a community feast and I was delighted to see how the young folks were incorporated and given responsibilities.

She showed us a photograph postcard, of Granny Clement making tea at camp while the family were tanning moose hides. She then introduced me to Granny Clement’s grandson, Jimmy, now one of the elders who I later saw instructing some of the young guys in Hand Game rules.

He scoffed at maps, knowing this region like the back of his hand and instead pointing in the direction of where his father had come from and where his mother was from. He shared local names of land features, told me a bit about what it takes to make a canoe (8-9 moose hides), and spoke soulfully of Great Bear Lake and of what he has seen up some of these rivers.

When I asked if I could share the stories forward he said no. Later, learning of the Heartbeat of Great Bear Lake, which is, “By any measure, the lake and its surrounding watershed is one of the last, best expanses of pristine wilderness on Earth” made his caution make sense, particularly as I learned more of how tenuous the balance of preservation and use is.

Kimberly graciously and openly answered our questions and we were able to inquire about topics we’d not yet had the opportunity of depth to broach. Why the children’s shoes in front of monuments at the Forts? What role do kids play in communities and how do the adults approach parenting? What are heating costs in the winter?

From things as light and funny as understanding ‘Dene Time’, to the underpinning reactions and pain from the impact of missionaries. It was all being stirred back up as the Pope was in the area to issue a formal statement, to the tune of $35 million cost to Canadian taxpayers. Needless to say, reactions were mixed.

To help us understand the matter, she encouraged that we watch the film “We were Children”, a 2012 documentary interviewing a few First Nations individuals who had survived the Canadian Indian residential school system. If you are interested to understand more, I encourage you to do the same.

[The rest of this post deals further with this topic. It comes from the perspective of someone from a country and culture not yet fully engaging with the ramifications of our policies and actions against indigenous peoples. It is further shaped by my upbringing as the daughter of missionaries and weaves in how the work the First Nations folks are doing, has informed my own.

I’ve never been one to tread lightly and I am certain I will get things wrong. I’ve done my best diligence before posting this. Reading forward is your choice and is primarily aimed at orienting those who are unaware or uninformed about what has been transpiring.]

Over 150,000 children were forced into residential and day schools from the 1870s to the 1990s. Some were outright kidnapped from their families and land, others were lied to and cajoled, other families sent their children willingly, believing in the promise and hope of education. Many of these children never came home and masses of unmarked graves on the school grounds continue to be uncovered.

Of the generations of individuals in these schools, most of those who are still alive are now parents and grandparents. They and their descendants are processing the intergenerational trauma and at the same time, are working to reconnect THEIR children to the ancient roots in this land. The wounds of this trauma were reopened with the visit of the Pope and the ongoing government efforts toward ‘restitution’ by asking folks to file paperwork of their abuses. Within the communities there are efforts to engage folks in therapy and other efforts to process.

Having grown up as a missionary kid, it was a lot to intake but somehow, the way Kimberly shared it made it inviting and imperative to step up to the work. On my own journey, recently bikepacking through impoverished regions of Central America, where the climate, plant life, and tenor of existence (poverty) had pitched me back to some of the formative and turbulent years of my childhood and adolescence. At the time I had not been in a place and space safe enough to work with it. I had sobbed, raged and tucked it away, promising Little Bethany we would come back to it “later.”

It was here that “later” began and the path yet stretches far ahead, for all of us willing to take that walk. It harkened back to some of the first nigglings which set me off on Her Odyssey. Incongruities in my upbringing which never sat well and which I could not comprehend, much less put into words. Now, 30 years later, the imperative to circle back as a way forward was nurtured by Kimberly’s joyful, frank, openness.

Comments (3)

Ohhhhh … I miss the north country .. thank you for bringing up wonderful memories of paddling in the north. It’s so vast and beautiful up there

Except the bugs lol.

Oh, you! Thank you for bringing us unknown or misunderstood worlds to us so vividly. My favorite line is this journal quote: “It feels like being a mite on the sleeve of someone giving a huge hug.”

Its fun to follow along on a journey that happened last summer, reliving all of the delights along the way like it occurred yesterday. I suppose that it should be noted that the Yerba that appeared in Fort Simpson was arranged to be there about six months before the fish gut bear destroyed Her-Odyssey’s supply.