August 24- September 1

We paddled into the pebbly beach on one of dozens of coves which frame the Inuvialuit hamlet of Tuktoyaktuk around 8:30 pm on August 24th. John was standing on the deck of the warming house/restaurant he built during COVID to compliment his wife’s bustling food trailer, Gramma’s Kitchen, and provide folks a comfortable and dry place from which to enjoy the area.

“Come up, have a beer, share your stories,” he called down the beach.

Neon and I laughed, hugged, whooped and snapped a jubilant usie (as opposed to selfie). As we tugged the boat up, I marveled that this stranger invited us in with, “share your stories,” the tag line we’d distilled over the course of Her Odyssey. John Steen would prove to have both a strong spine and deep intuitions.

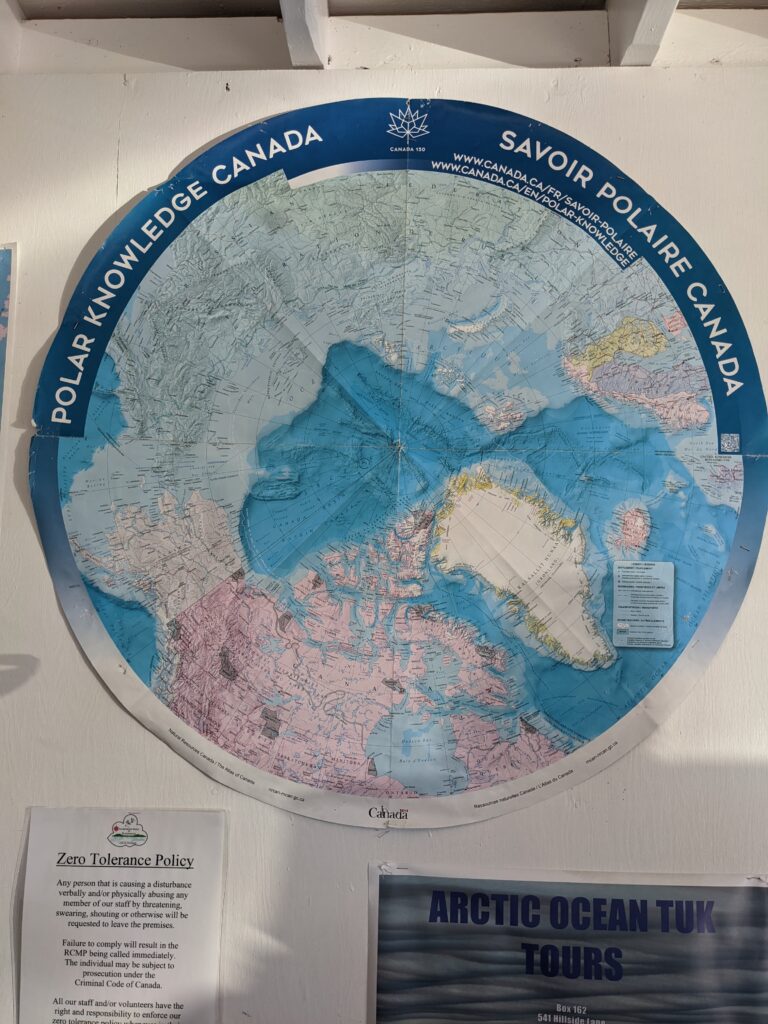

Up at the dining hut quite the welcoming committee happened to be gathered! Two of the Steen siblings (John & Annie), Erwin Elias the Mayor, Eddie Lucas, and Bruce Noksana, one of those invaluable sorts who can get anywhere and make anything work. All have deep blood-ties to this land.

They welcomed us heartily and heard us out, sharing stories in turn of the journey of their own community and the other big dreamers and Arctic voyagers they had adopted, like Saturo Shanti Yamada. We come straggling in from all reaches of the globe: Japan, Ireland, and “down south”, which is pretty much everywhere.

They shared bits of muktuk, suggesting that the secret is to dip the cubes of whale meat into a bit of salt and douse it in steak sauce. Amongst the elders in particular, everyone had their favorite length of time to let whale oil spoil into a sort of dipping sauce.

Erwin explained that some like it green, others yellow, while white is apparently the mellowest flavor. I’ve never been more grateful for A-1 sauce.

By midnight I was out for a sunset walk along the beach with some of the women. Business owners, photographers, advocates, seamstresses, and hunters; every last one of them. They kept an eye out for beluga whales and speckled belly geese. Watching the animals was a natural extension of their way of life, always information gathering from the other populations. They each stooped down periodically to inspect particular rocks.

Gramma wrote her name in flowing cursive with a stick in the sand.

“‘Joanne Edds Steen,’ my last name [Edwards] without the ‘war’. No violence!” she chuckled.

I immediately liked her and still with each new thing I learned from or watched her do, I admired her only more. On top of being her own creative self, a businesswoman, wife, mother, and grandmother, she was also who you brought your sewing machine to if it needed fixed, or the once a week when the town got homemade pizza.

But it wasn’t just all sewing projects and baking with Gramma; she also loves riding motorcycles, rock n roll, and was a Sheriff to hide your truck from. I followed her between house and kitchen trailer a few times and couldn’t keep up. “It’s all in the hips,” or “Moving fast is how I stay young,” she’d laugh over her shoulder as she darted about.

Annie was John’s little sister, visiting from Yellowknife. She is a mover and shaker; if there is anyone or anything interesting going on, Annie knows about it. If you need anything, she’ll find it. She’d also had contact with almost every notable explorer who had traipsed up this way, especially exceptional women like Dianne Whelan and Remote Leigh. Herself being widely traveled, connecting the web of us is one of her many community affirming projects.

She spoke and worked passionately on fundraising for a Cultural Arts Center in which precious artifacts could be preserved, thus undermining one of the pretenses the prominent museums and religious establishments excuses for not returning stolen cultural artifacts. It was she who explained that on the beach, they’d been looking for rocks with holes in them; what my ancestors would have called Hag Stones. I later noticed a few women proudly showing such finds among friends when they’d go visiting.

![]()

Bruce offered that we could stay at a house right next door to Gramma’s. This gift gave us the time to savor and transition. The next morning, I woke to window panes dripping with condensation and the view entirely socked in. I sat with a mug of tea and stared into the shroud.

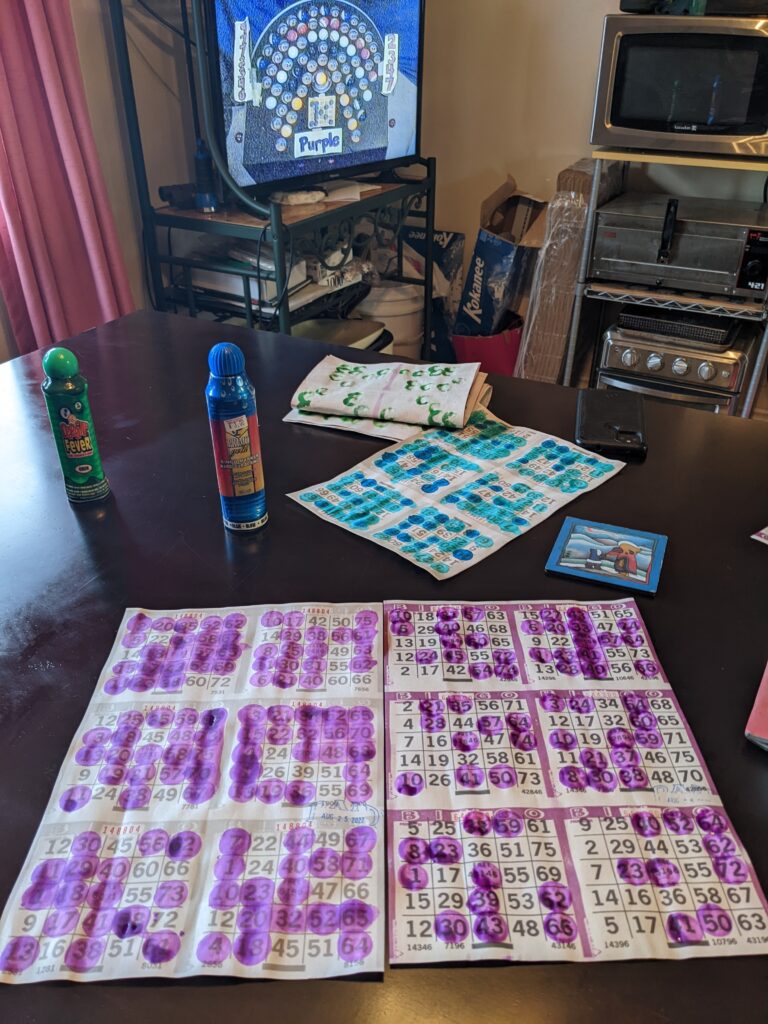

Gramma was a living invitation to engage and ground in the now because she always had something going on and she folded time and tasks like dough. I was honored in my little part of lighting the fire in the dining hut each day, then to be amazed when we sat down to Bingo prompt at 6 and hear how many people she had fed in the meantime.

While bustling around the kitchen in the first days she suggested, “while you’re here, you should sew something.” Both Neon and I jumped at the opportunity and she pulled out a wide variety of patterns of garb like kuspuks, mittens, beanies, you name it, she has a pattern for it (and if she doesn’t, she’ll make one). Neon and I both immediately chose slippers, reasoning that our feet deserved a bit of extra love and thanks. Between her and Annie to guide us at each step we ended up with lovely treasures of a story well trod.

Thus a routine developed.

Excerpt from Journal 8.26.22

“I wake to sleep and take my waking slow.

Sweat through my bag, bummer because yesterday we had showers and done laundry.I sew and sip tea, watching the fog roll out in tendrils, moving like shadow reflections of northern lights. Today is windier. Sunlight falls through the window only now, noon thirty.

Neon had another bout of debilitating cramps, so I’ll clean the boat and go to the appointment at the Hamlet Office per Erwin’s invitation by myself.

When I hauled the bucket and sponges out to scrub The Arctic Tern for the last time, Gramma appeared at my side. “I always used to clean the boats with my dad,” she smiled, making quick work of it.

She asked about Neon, disappeared into the food truck then reappeared with a jar of pickle juice. That and putting onions around yourself to draw out sickness are a couple of the remedies known to this Gwich’in princess.

Neon received it and a warm water bottle before rolling back into herself, croaking, “male explorers have no idea what we go through out here.”

Outside the Hamlet office I got to chatting and laughing with a small cluster of women. As it turned out, among them were 2 of the 4 in town who were among the first women to have harpooned beluga whales. They were also the town administrators who’d been asked to acknowledge the completion of our undertaking and I could not have felt more honored. Annie had given us a primer on the history of this cultural evolution of women into whale hunting the night before. Traditionally it was a group effort and male only sport and she’d concluded with, “our culture is evolving, and fast.”

“It’s the time of the women,” Gramma’d added.

Regarding hunting in particular, tangibles such as development in weapons and, most dramatically, the arrival of motors had revved up access and ease for hunting. That journey alone, from hand made, arm length measured kayaks to metal vessels is fascinating in and of itself. Layer that atop learning they still throw the harpoon by strength of arm. Katrina explained that the hunter perches at the tip of the prow, gripping the boat between their legs and leaning out over the water, hurls downward with (hopefully) enough force to pierce the thick skin and blubber.

On top of the physical, cultural, and evolutionary aspects of the hunt, there was the practicality and oversight of management. Thus, they were also all very invested in politics and family of electing leaders who take an overarching view of management practices. Collaborating with Parks Canada, they worked with scientists to collect data on belugas, caribou, reindeer, grizzly, and many other populations.

In 2022 they had ‘pulled in’ 30 whales and had systems for tagging them as well as distributing the meat throughout families and community, with special provisions made for elders. The scientists had taught them to harvest 2 year olds, usually of a lighter color. “They said the older, big bulls are full of mercury,” Bruce shrugged. I also wondered at the evolutionary advantage of letting large bulls live. I thought of the roaring feral cattle in Los Glaciares, Argentina.

Once an animal is harvested, family come out to help dress and celebrate it. The very heartbeat and lifeblood of all the hunting and fishing sites we had passed when silent. They showed me pictures filled with lives, smiles, food, tea, and abundance.

Their ties to these and other animals showed up in everything: from the food on the table and stories they tell, to the handles of their blades and what they carve into wood, marble, and bone. One can even see it in their movement and travels throughout the days, seasons, and lifetimes.

A practical people, the hamlet is laid out with the nursing home next to the cemetery, across the street from the Health Centre. Here too life ends with a white picket fence. Just as it had for the Onas on Tierra del Fuego. Except, there are no Ona left; but here, the Inuit remain living with their eyes wide open to everything happening around them. Whereas on TdF there were nameless bleached crosses, here, every marker had a name, and flowers and other offerings colored the grounds. We recognized some of the names, children and ancestors of those we’ve met.

In this way, they move with the land. A matter which still eludes the scientists, who keep losing their equipment to it. Meanwhile, the locals shift houses and buildings around on skids atop snow during the winter as the land sinks in the thaw of hotter summers and darker surface which thereby attracts more sunlight. At the same time, lakes are disappearing. Sucked right back down into the land. Bodies of water which some can imagine as footprints of giant ancestors.

Considering the presence of mega fauna, it’s easy enough to reckon up huge human forebearers, especially on land this vast. Or, think about stovepipe grass, their ancestors were 40 ft tall! Alternatively, we can go the opposite way. Teosinte into Maize into Corn. Don’t pretend like we are living in anything other than an Alice in Wonderland-esque journey of shrinking and expanding then collapsing into our own tears.

Speaking of pastimes…

Berry picking is as pivotal a focal point as hunting. Both mark the turning of the seasons, fill the pantry, and connect the soul of the community to its land and history. Of course there were the blueberries, currants, and raspberries but perhaps this patch is plumper, or you’ve found some of any of the dozen other species.

Each berry has its own peak season and everyone, especially the elders, have their favorites. So for example, Betty, a former teacher and one of their language keepers, explained that she was saving herself for the Cranberries, knowing just when and where she would go looking. Annie swore by the Cloudberries. Granny had baggies and jams of varieties.

On the Hamlet Office bulletin board there was an invitation to youth and elders for a berry picking mission. We’d see them whizzing off in speedboats toward different channels or secret family patches. Only to come back and report exactly where they’d gone to one another in such specifically vague terms that only someone who had stood at the exact spot would understand.

I did pay attention when a report came in of one family turning around at the dock to their camp because a young polar bear had taken up seasonal residence. It had been “a good way up east” and they’d had a gun but preferred to avoid confrontation for the time being. I was again grateful to be in the middle of human settlement.

In this way, everything we learned about the land taught us more about the food, and vice versa. While the traditional community freezer is set below ground in the permafrost and is no longer open to the public, they certainly open their pantries to their guests. Gramma shared her Bannock recipe and the next night we [mostly Neon] made chili and cornbread, deemed, “the bannock of the south.”

Some days we got to help with tending the oven and 72 buns and loaves set out to rise every other day on the kitchen table for the restaurant. Then, from 6-8 pm all else would be swept aside, the table cleared, TV turned on and tuned in for Bingo. I’d never played Bingo before and was often distracted from my own 1 or 2 cards by being amazed at Gramma and Annie running 6 of their own while also pointing out numbers Neon and I had missed on our own cards, on top of taking buns out of the oven!

Speaking of tending to many pots and Bingo…

Most night folks drifted by, ‘going visiting’, and a couple of times they hosted family feeds. This occasioned Neon to appear one afternoon from the back porch freezer with a Caribou spine in hand.

There was a bow saw on the heavy cutting board at the round table island in the kitchen. Gramma flew through grabbing ingredients needed out at the restaurant and gave quick instructions on how to cut it up and lay it in the roasting pan, what temperature to set the oven, and start it toward becoming soup.

Another time, from that same freezer, I watched Gramma produce a full frozen goose and present it, a tub of peanut butter, and most prized to all, a shower with clean towels, to 4 European sailboaters on their way through to Kotzebue. They had 9 days and were racing the cusp season. I thought of friends there. I’ve also often wondered about flinging myself out across horizonless water.

One particular feast was for Joanne and John’s anniversary, featuring a 22 lb salt water lake Trout Salvelinus namaycush which John had caught at Husky Lakes. As family gathered, food piled up. A cousin had made a beautiful cake. We sat up into the wee hours of the morning sewing and playing 31 and the guys headed out to the garage. Yawning by 11, I was chagrined to realize we could barely hang with the elders who were still chatting and laughing at 3 am. “We do all our sleeping in the winter,” Betty explained.

As a table we summarized the conversation about what features stood out about Tuk into a little poem:

In the land of the Pingo

Where I first played Bingo

Learned a bit of the Lingo

Looking for my Ringo

Instead I met Gringo.

I mentioned getting a call from an unknown number that morning, a woman who lived in Inuvik, whose cabin we had crashed in somewhere along the Big River. She’d wanted to tell us that note I’d left was delightful and that if we’d “just poked around a bit you’da found the keys and could let yourself into the house.” I thanked her, that what they’d left open to share more than met our needs. Betty had listened with interest and then asked for a name. “Ah yes, they have the gray cabin.”

“with the red trim,” her niece added.

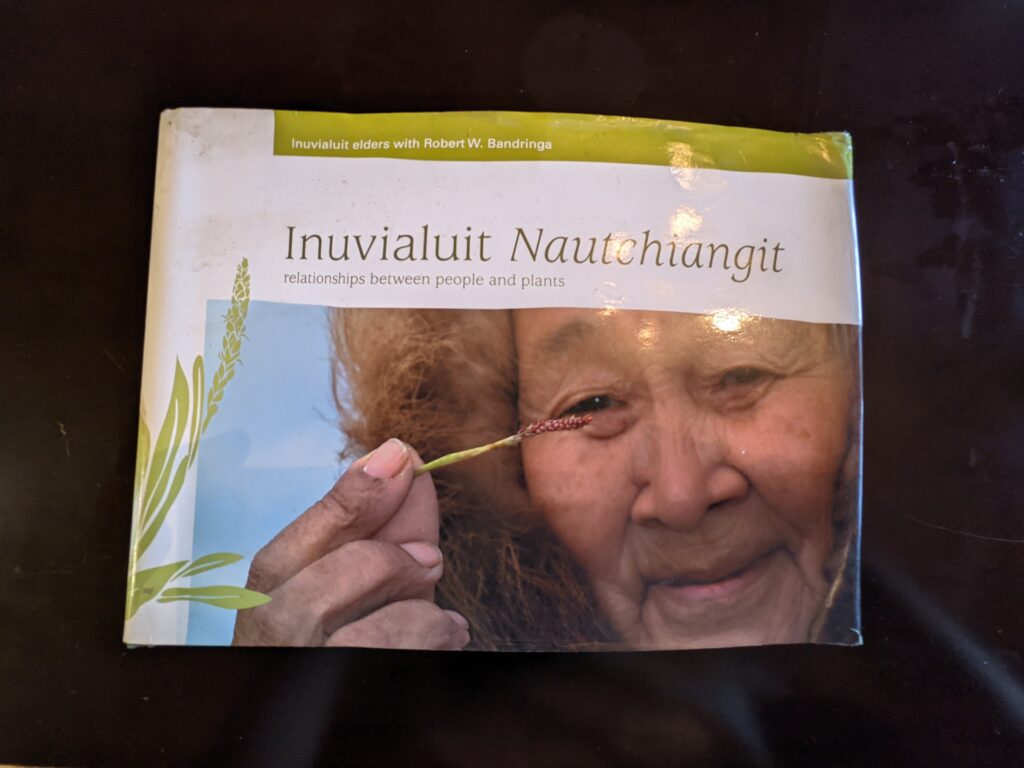

With this keen mind, Betty kept us enthralled and sometimes in stitches, teaching a colorful array of Inuit words and expressions. For months, Neon, ever the tracker, had been noticing the Inukshuks who peppered our path north. Granny had introduced us to the Ulu, a traditional women’s blade. Betty named the eternally present Siqiniq (Sun) and explained the amagok, which directly translates as sunburst, but which refers to the plush, radiating frame of fur around the hood of a woman’s attigi (parka). Deadly, which we kept hearing on the call in radio show, meant “awesome” or “cool”, as in “that song was deadly.” I’ll leave the more imaginative applications of terms for the figure of a sunburst at that table and to your imagination.

Speaking of humor, language, and roots let me tell you about…

Bruce of Noksana Mushing

One of my favorite evenings in Tuktoyaktuk was visiting with Bruce and Michele of Noksana Mushing. A couple days after meeting Bruce that first night, we bumped into Michele at the grocery store. She’d just returned from Africa and was brimming to talk travels. A subject on which I am always an enthusiastic yes!

They gave us the royal tour of Tuktoyaktuk. Bruce’s family have long been involved in the development of this community and he frequently cited his granny, Persis Gruben, as a central figure in his life and that of the town (backed up by her being carved into a stunning 5000 lb marble statue in the park).

They took us up to the high point overlooking the hamlet, pingos, and landscape. We shared the view with one of the DEW Line towers (Distance Early Warning System) and by coincidence, Senator Margaret Dawn Anderson. They’d gone to Sunday School together.

Michele had been a field journalist and is now the Vice Principal in town, so her journey and perspective resonated with me. While I was interested to hear graduation rates and insights from an educator’s perspective, what made her commitment resound was how she showed up for her students and families, stopping at the youth center and hopping out of the truck to talk to students.

“You don’t get anywhere when you go with her,” Bruce jibed gamely. Later in the drive she was gushing about a cookbook the elementary school had put together, a collection from the kids of their parents and grandparents’ recipes.

They also took us out to a lovely viewpoint of the pingos. While we have limited scientific understanding of these permafrost pimples, the Inuit know them all by name, have long used them as navigation beacons, and to this day take the kids sledding on ‘em in the winter.

No Northern tour being complete without a visit to the dump, this one also wended past the water treatment facility. Supplying clean water in a brackish environment and managing waste is a particular challenge in a sinking, eroding landscape. And the man responsible for it in the community was sitting in the front seat.

No Northern tour being complete without a visit to the dump, this one also wended past the water treatment facility. Supplying clean water in a brackish environment and managing waste is a particular challenge in a sinking, eroding landscape. And the man responsible for it in the community was sitting in the front seat.

There was a bit of heated debate up there about leaching from the appliances in the dump into the rising sea. A problem for the environment, endemic to human settlements. Same as our dumps and the bears. From what I understood, they were doing the best they could and learning and adapting as quickly as possible. As Bruce later summed up one of his life philosophies, “Work hard, don’t hurry, teach what you know to others and that’s what I have to say about that.”

From town, we headed out to their corner of the world and 37 dog lot. While we had never before pulled in nets, nor gutted and filet white fish, Bruce moved with efficient ease. As I struggled through a filet he told us, “Failure is a white man word. There is no word for that in Inuvialuit. If you don’t do it good, then you don’t do it good and you just keep practicing.”

In the time it took him to say that, he had filleted a whole fish with the duller of the two knives and separated it into baggies for the house and barrels for the dogs. He’s worked with warriors like polar bears and oriented military troops to the environment. He was patient and encouraging, having taught these skills many times before. This combination of knowing the land better than the back of his hand, combined with a natural capacity for story telling and skill sharing, and a generous, jovial demeanor made it clear why he owned a guiding business.

He knew everything from details of flora and fauna to creation myths and wove them together. For example, showing us that grass along the ocean bank is both most effective and reduces the smell for cleaning hands and table after gutting fish and anyway, then there is no trash from wipes and chemicals.

Not a man to waste, first we stopped by to meet the sled dogs, and toss the fresh hunks of fish to each athlete. It reminded me of being on Denver Glacier with Alaska Icefield Expeditions, seeing those musher/team bonds. This pack followed Bruce’s every move and he, in turn, knew their every personality and family line, introducing them all, from the Lead Dogs to the collarless lurker hiding out under the water donkey.

Not a man to waste, first we stopped by to meet the sled dogs, and toss the fresh hunks of fish to each athlete. It reminded me of being on Denver Glacier with Alaska Icefield Expeditions, seeing those musher/team bonds. This pack followed Bruce’s every move and he, in turn, knew their every personality and family line, introducing them all, from the Lead Dogs to the collarless lurker hiding out under the water donkey.

From there we went to their home where he toasted up ‘pipes and eggs.’ At some point during the meal his daughter appeared and shared sushi she had made. At every turn among these folks, when I thanked and marveled aloud at their kindness and hospitality they replied simply saying,

“generosity is part of our culture.”

Concluding the Expedition

One afternoon we walked the last mile or so through town, down the pebbled spit past where the Dempster Highway ends. The stones and sandy mud ooze between my toes. The cold makes my skin pimple and retract, contouring every vein, tiny bone, sinew and nerve. Blue blood pumps life and I wriggle 10 little piggies, promising them all the attention and comforts they desire for having gotten us here.

I threw myself open and exalted in thanksgiving. I laughed, watching salty tears spout off my cheeks into the sea. There is a reason we’ve long weaved tales, poetry, and song of weeping into water. It is a physical suffusion of self with place. One of the gifts that comes by your very being.

I felt a sense of Whole Being. The sun, warm to several layers inside my skin, making the gentle wind prickle as every exposed hair stood on end to get a better view, making space for the crackling radiation flowing out of me and into everything around us.

At that moment, the Canadian Coast Guard Boat appeared on the horizon. Neon had joined me in the shallows and we doubled over, roaring in laughter. Then held one another and together we celebrated, whooping and splashing. A young woman who had driven up here sola with her two fluff clouds of dogs joined us in reveling. Out here, we find one another.

We dutifully waited our turn with the various signs and took dozens of photos for our gear partners and sponsors. We were interested to see a colorful Trans Canada Trail Monument atop a small rise. We had seen a ‘TCT Route’ on the Deh Cho length of the Gaia River Maps overlay and now that mystery was solved.

Then we sat back and did one of our absolute favorite things in the world, people watch.

Out on the point it was us tourists. Family RVs erupting with children who roved and squealed in different languages at the cold water. There was an elaborately rugged and shinny red truck full of YouTubers. The #vanlifers. The elderly on van tours, checking off bucket lists. Two packrafters whom we watch with fascination loading up and heading out on placid waters. We checked the weather forecast reflexively on their behalf.

There was the local fellow selling little beaded trinkets his sister-in-law had sewn. The elder woman working with a hammer to untack the tarp roof from her little sales stand. I swung by on our way back to offer help but she had matters well in hand.

We scoped out the ship school, Our Lady of Lourdes, a winding tale unto itself. On the way home we exchanged greetings with folks, some we recognized, others we did not, but soon would. I suppose it is to be expected in a community of 900 where many are on foot or four-wheeler.

When we got back to Gramma’s that evening, I headed to the end of the beach alone and slipped into the glassy water. I swam, playing with the reflection of the pingos, setting myself in the bosom of their reflection and then becoming still. Gazing into blue sky, across vast land, into and under clear water.

Altogether we spent a little over a week in Tuktoyaktuk. The folks we met and the community they welcomed us into beautifully capped both the mission and heart of the Her Odyssey Expedition.

The reality of it began to settle in as we ambled back through town, at a more leisurely stroll now that we had covered 18,221 miles and 125* of the arc of the globe.

Comments (2)

Amazing journey!!!! Thanks for sharing so much of it with us here ?

Thank you, sister! Stoked to support as you step into hero mode. ? ?